The Church at Auvers, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890 | © Public domain / WikiCommons

January 31, 1873, ended in calamity for Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894). It was the day his parents, members of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, discovered his disbelief in Christianity. On February 2, he confided in his close friend Charles Baxter in desperation, and his letter, worth quoting at length, paints vivid and strained outward and inward scenes:

My dear Baxter, The thunderbolt has fallen with a vengeance now. You know the aspect of a house in which somebody is still waiting burial—the quiet step—the hushed voices and rare conversation—the religious literature that holds a temporary monopoly—the grim, wretched faces; all is here reproduced in this family circle in honour of my (what is it?) atheism or blasphemy. On Friday night after leaving you, in the course of conversation, my father put me one or two questions as to beliefs, which I candidly answered. I really hate all lying so much now—a new-found honesty that has somehow come out of my late illness—that I could not so much as hesitate at the time; but if I had foreseen the real Hell of everything since, I think I should have lied as I have done so often before.... Of course, it is rougher than Hell upon my father; but can I help it? They don’t see either that my game is not the light-hearted scoffer; that I am not (as they call me) a careless infidel: I believe as much as they do, only generally in the inverse ratio; I am, I think, as honest as they can be in what I hold. I have not come hastily to my views. I reserve (as I told them) many points until I acquire fuller information. I do not think I am thus justly to be called a ‘horrible atheist’.... What is my life to be, at this rate? What, you rascal? Answer—I have a pistol at your throat. If all that I hold true and most desire to spread, is to be such death and worse than death, in the eyes of my father and mother, what the devil am I to do? Here is a good heavy cross with a vengeance, and all rough with rusty nails that tear your fingers: only it is not I that have to carry it alone: I hold the light end, but the heavy burthen falls on these two.

Defeated, Stevenson signs the letter with a somewhat punitive and self-deprecatory quip: “Ever your affectionate and horrible Atheist, R. L. Stevenson, C. I. [Careless Infidel], H. A. [Horrible Atheist], S. B. [Son of Belial], etc.” This wry turn on a serious subject is very like Stevenson, who impressed others throughout his life with his ambiguity—fluidity and flux, coupled with a sense of stability and continuity, in both his person and writing. Even here at the age of twenty-two, Stevenson rejects the names his father applies to him, only to adopt (and embellish) them in the next moment, his identity rippling or flickering as it were in the absence of more accurate labels he could honestly espouse.1

This textual snapshot also speaks to Stevenson’s frequent role-playing, to his semi-assumption of identities put upon him by others. As a writer, this habit suited Stevenson. When he was young, he intentionally mimicked a variety of genres and voices as he sought to establish his own style. Famously, Stevenson always kept with him a book to read and a notebook to write in, seeing his role as a man of letters as dual, comprising the (immersed) consumer and the (imitative) producer.2 One might say his chameleonlike nature is what enabled him to compose such romping adventure stories and splendid pieces of historical fiction as Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886), and David Balfour (1893); such poignant poems about childhood and childlike thinking, as seen in A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885); and such dark morality tales of duality and possession, epitomized in “Thrawn Janet” (1881) and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). But it also served him well as a method of self-experimentation, or identity questing, and of reflection on the moral function of literature.

This role-playing comes to the fore in his travel writing, particularly Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879). Intimately tied to Stevenson’s spiritual quandary and problematic relationship with his parents, this text offers readers a valuable glimpse into an all-too-common dilemma: What to make of ourselves, of our identities, when we reject or revise or challenge the faith (or as sometimes happens, the no-faith) of our upbringing? How does one resolve the ensuing tensions, inward and outward? Remake relationships with the past? Engender self- and other-understanding?

These questions were further compounded by recent events in Stevenson’s personal life. The writing of Travels came at an especially difficult period of loss and self-doubt. In 1878, Stevenson lacked certainty about his professional prospects; his relationship with his parents was strained by money matters; he continued to struggle with the chronic health problems he had experienced since he was a child; and he was lately in love with an American woman, Fanny Osbourne, who had just left Europe and returned to her home in California. Stevenson knew he would need more income if he wanted to see her again or to propose marriage. He planned his journey in the Cévennes partly as a financial venture, with the aim of rapidly publishing a book based on his journal.3 Readers will find as they roam the Cévennes with Stevenson that he cuts an unorthodox and unstable religious figure in the pages of Travels, a mock pilgrim who slips in and out of a range of identities. Stevenson is the peddler, the stranger, the historian, the Englishman, the Scotsman, the author, the heretic, the preacher, the Protestant—all depending upon his companions and onlookers. But, like a genuine pilgrim, he is also a seeker, keeping eyes on his heart as well as the road.

***

In autumn 1878, Stevenson embarked on a twelve-day trek through the Cévennes, a mountainous region in south-central France, from Le Monastier-sur-Gazeille to Saint-Jean-du-Gard—a distance of two hundred kilometers. The journey begins with Stevenson’s purchase of a she donkey, whom he “baptise[s]” Modestine, perhaps to satirically invoke the virtue of modesty in a genre that, at the time of Stevenson’s composition, was fast becoming more about the traveler than the lands traveled.4 Modestine’s name and Stevenson’s choice to “baptise” her are also consciously religious, inflecting the work at its outset with a religiosity that it never completely owns. In fact, Stevenson alternately shrugs off and accepts religious identities throughout this text—just as he rejected the labels “horrible atheist” and “careless infidel” from his father only to assume them again, trying them on.

He tries on an iconic Protestant guise in the book’s opening pages. While authors since John Bunyan (e.g., Charlotte Brontë) have typically used Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) to emphasize the hereafter, Stevenson alludes to this fictional puritan biography throughout Travels to emphasize the here and now. After christening Modestine, he drolly adopts the image of Bunyan’s Christian with his burden, his allegorical sins (supposedly) in view: “Like Christian, it was from my pack that I suffered by the way.”5 This religious textual reference seems to identify Stevenson as a serious spiritual pilgrim, but he takes the sincerity of the association away in the next instant, sweeping the rug out from under us: “If the pack is well strapped at the ends, and hung at full length—not doubled, for your life—across the pack-saddle, the traveller is safe.... There are stones on every roadside, and a man soon learns the art of correcting any tendency to overbalance with a well-adjusted stone.”6 Ever the adroit narrator, Stevenson reduces the pack in question to a problem of balance and gravity, deftly sidestepping its religious implications. This signals a complex doubleness of self. It is humorous in tone, yes, but it also glances off the serious heart of this work, speaking as it does to Stevenson’s impossible position: his discomfort with a break from his denominational past and unwillingness to leave it (and his parents) completely behind, and yet also his inability to accept the Christianity he inherited.7

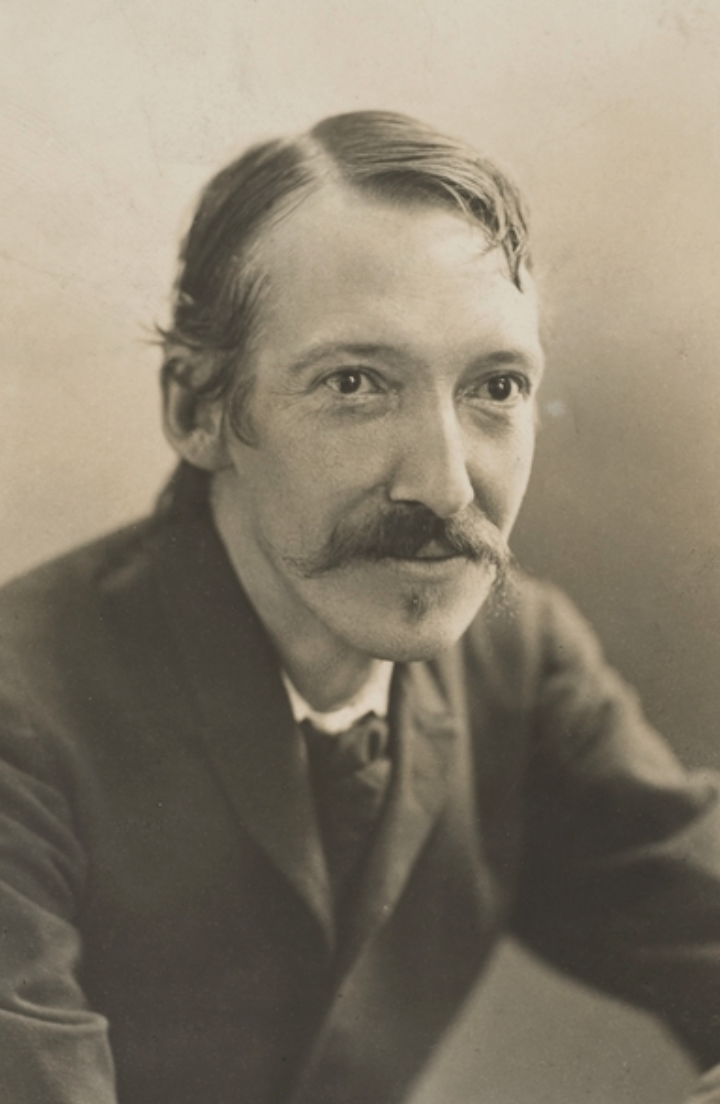

Robert Louis Stevenson, 1893

And Stevenson must have, indeed, seen his position as one he could not sustain. At the age of twenty-seven, his choice to travel in the Cévennes and nowhere else was very intentional. The region attracted him because of its religious history, specifically the Camisard revolt of 1702–1705. The Camisards were Protestant guerilla fighters of the Cévennes, descended from the Huguenots, or French Protestants, of the Reformation. They fought for their religious freedom during the reign of Louis XIV, following his Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. The Edict of Nantes, issued in 1598, protected the Protestant religion in France, and its cancellation meant oppression and forced conversions to Roman Catholicism. Armed resistance broke out in 1702 and officially lasted until 1705, although violence flared for another decade between Catholics and Protestants in the Cévennes.8 For Stevenson, the Camisards paralleled the Covenanters of Scotland, who following the restoration of Charles II to the English throne in 1660, resisted the new king as head of the Church. Like the Camisards in France, the Covenanters in Scotland symbolized staunch allegiance to religious principles, spiritual heroism, brazen zeal, and martyrdom.

As a child, Stevenson was raised by a God-fearing nanny, Alison Cunningham, who told him stories of the Covenanters. These stories framed a significant part of Scotch and Presbyterian identity for young Stevenson.9 As an adult researching the history of the Camisards, Stevenson wedded the two sites of brutal religious and political strife, seeing in the Cévennes history and landscape an opportunity for self-reflection away from home. In Travels, he frequently blurs the Camisard-Covenanter divide, sometimes playfully transposing historically specific words—such as when he applies the term conventicles (used for the Covenanters’ practice of holding private illegal meetings) to the Camisards.10As narrator, Stevenson periodically takes on the identity of a Camisard, hiding in the landscape to sleep outdoors undisturbed by passersby: “I concealed myself, for all the world like a hunted Camisard.” But he also renounces the association as if to hint that he is not worthy of it, admitting he was more afraid of “visit[s] of jocular persons in the night” than a Camisard would have been of being discovered and killed by Catholics, “for the Camisards had a remarkable confidence in God.”11

The artful implication in this instance is that Stevenson’s confidence in God is lacking. The whole of Travels makes much of Stevenson’s fears, embarrassments, annoyances, and shame. Stevenson’s friend and fellow Scot Andrew Lang (1844–1912) called Stevenson “always a boy... immortally young,” and it is true that as a writer he does what children do best: play.12 He plays with identity, with genre, with ideas of knowingness, with history, and with the reader, always to see what he can make of them. In Travels, he adds to this his play with his uncomfortable emotions—subtle experimentations that sound his heart. He is often embarrassed in the eyes of locals, who laugh at his inability to handle Modestine, or else he is afraid of dogs and unwanted visitors during nights spent outdoors. His inability to be perfectly just makes him uneasy; he feels much more at home among the Protestants of the Cévennes than among Catholics and questions his innate partisanship. He longs, too, for Fanny and their bond of familiarity. The text never mentions her explicitly, but several narratorial comments about pairs, love, and women hint at their trial of separation.13 At times, Stevenson loses his temper. More than one passerby on the road mistakes him for a peddler, to his growing aggravation. He is “annoyed beyond endurance” when a Catholic priest asks him “many questions as to the contemptible faith of [his] fathers” and then “receive[s] [Stevenson’s] replies with a kind of ecclesiastical titter.”14

This exchange occurs at the Trappist monastery Our Lady of the Snows, a place that serves as a catalyst for many of Stevenson’s disagreeable emotions. He approaches it with an irrational dread, “creaking in [his] secular boots and gaiters.” Having been raised as a Protestant, he admits to his anti-Catholic prejudices and grumbles at the “slavish, superstitious fear” built up within him: “I have rarely approached anything with more unaffected terror than the monastery of Our Lady of the Snows. This it is to have had a Protestant education.”15 The monastery is also the site of Stevenson’s resistance to conversion to Catholicism. He withstands two French boarders, “bitter and upright and narrow, like the worst of Scotsmen,” when they try to convert him to Catholicism over morning coffee.16 This episode forms one link in Stevenson’s chain of reproving references to missions and religious persecution throughout Travels. His tone may be droll and sardonic by turns, but at bottom, Travels is a heartfelt work characterized predominantly by the seeker’s prerogative: the free admittance of not knowing.

In this, Travels accomplishes something crucial when it comes to its religious subject matter. It invites contemplation of the similarities and differences between denominations and the world’s religions. Stevenson raises a quality of question that applies more to relationships between diverse religious perspectives than to any one religion in particular. (Stevenson’s odd reference to Buddhism, which may take some readers by surprise, makes sense in this regard.) And as with all else, the aspect of play persists. Stevenson brings the difficulties of weighty subjects—his shortcomings, his religious bias, and the disturbing histories of religious persecution that erupt when religious bias is unchecked—into his playfulness as a writer. We learn from Stevenson that no subject is too serious for play. “Fiction is to the grown man what play is to the child; it is there that he changes the atmosphere and tenor of his life.”17 The genuine nature of Stevenson’s Cévennes journey—a deeply felt project of personal experimentation with his past and beliefs—may be frequently evaded in Travels, but the book demonstrates an important principle at the heart of Stevenson’s view of literature: that we learn how to adopt right attitude and right action (and perhaps also right belief) through play.18 Play involves embracing the unexpected and uncertain, a difficult skill to master. For Stevenson, it offers a valuable form of self-instruction, a method for handling a difficult period in life as he navigates his relationship with his parents, his need for their financial support, and his love of Fanny. In many ways, Stevenson’s playfulness resonates with his role as seeker more than his role as skeptic. Children play in order to learn and improve. It is both practical and ethical, involving consistent effort and a spirited attitude.