Consciousness and the Future of Humanity

I hinted earlier that the problem of AI comes down to the difficulty of explaining the nature of human consciousness. Moreover, the proponents of Dataism begin with the assumption that empirical and experimental science is the only genuine method of explaining the nature of reality, a highly controversial metaphysical presupposition not shared by all scientists. In this paradigm, consciousness is seen as another scientific problem to be solved scientifically. Such attitudes align well with the prevailing global tendency to ignore nonmodern, traditional philosophies, which developed highly sophisticated methods and theories to investigate the nature of consciousness over the course of thousands of years.41 The insights on which I base my argument that it is impossible to build an AI with a human-level consciousness are beholden to these traditions, especially to Islamic philosophy.

Consciousness is characterized by an absolute immediacy that transcends all objectifiable experiences, so it is futile to think of consciousness as a “problem,” since doing so objectifies it. Moreover, if consciousness must be proven in the same sense that, for instance, the table or the tree is proven, then consciousness is just one object among others, at which point any talk about consciousness being the unobjectifiable ground of experience becomes a futile attempt to prove what does not exist at all. In addition, there is no reason to think that consciousness comes into existence only when there is an I-consciousness in relation to an external object, since our logical sense demands that consciousness must exist first, in order that it may become self-conscious by the knowledge of objects with which it contrasts itself. More elaborate proofs show that consciousness can only be the underlying subject in all of our experiences; hence, it must be more fundamental than both our reflective and intersubjective (involving multiple) experiences. It suffices here to note that consciousness is a multimodal phenomenon having nonreflective, reflective, and intersubjective modes.42

With this background in mind, let us look at Searle’s definition of consciousness, which is widely discussed by many AI experts:

Consciousness consists of inner, qualitative, subjective states and processes of sentience or awareness. Consciousness, so defined, begins when we wake in the morning from a dreamless sleep—and continues until we fall asleep again, die, go into a coma or otherwise become “unconscious.” It includes all of the enormous variety of the awareness that we think of as characteristic of our waking life. It includes everything from feeling a pain, to perceiving objects visually, to states of anxiety and depression, to working out crossword puzzles, playing chess, trying to remember your aunt’s phone number, arguing about politics, or to just wishing you were somewhere else. Dreams on this definition are a form of consciousness, though of course they are in many respects quite different from waking consciousness.43

The first thing to observe about the above definition is that it is nearly tautological. Searle had to use the word “awareness” a couple of times to define consciousness. It is similar to the problem of defining “being”: one cannot undertake to define “being” without beginning in this way: “It is…”; to define “being” one must employ the word to be defined.44 The same happens with the term “consciousness,” which cannot be defined inasmuch as it is the ultimate ground of all knowable objects. Whatever is known as an object must be presented to consciousness, and in this sense, it is both the reflective and nonreflective ground of all things and of all intersubjective relations. In order to be defined, “consciousness,” much like “being,” would have to be brought under a higher genus, while at the same time differentiated from entities other than itself belonging to the same genus. However, this would violate the premise that it is the ultimate knowing subject of all known objects.

More importantly, Searle’s definition neglects the multimodal structure of consciousness that comprises reflective, nonreflective, and intersubjective modes—the multimodal structure that poses the greatest threat to the computational-reductionist paradigm that seeks to explain consciousness in terms of sentience or functional properties of the mind.45 This paradigm prompts computer scientists to transfer all mental characteristics to consciousness and analyze it in terms of specific mental events or states. It is no wonder that, according to Searle, consciousness “begins” when we start our day from a dreamless sleep and lasts until we fall asleep again—that is, consciousness is a subset of the wakeful state. Hence, consciousness is excluded from nonreflective phenomena such as dreamless sleep, coma, or intoxication. Consequently, scientific literature shows that dreamless sleep lacks mentation, whereas traditional philosophies consider it an instance of peaceful, non-intentional, and nonconceptual awareness.46

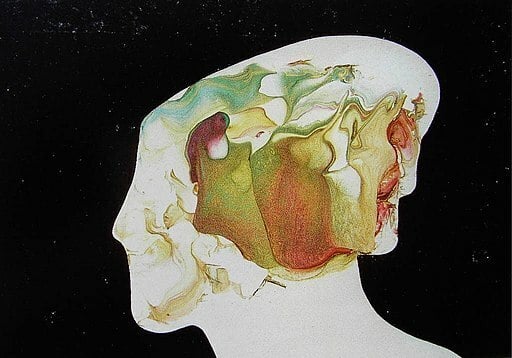

The concept of non-reflective consciousness brings into the open the furthest limit of the purely empirical approach to the study of consciousness.47 This is because consciousness is a first-person phenomenon, and such phenomena are irreducible to the third-person objectivist stance that characterizes various computational-functional theories of consciousness. Moreover, since consciousness is the very essence of human subjectivity, there is no way to step outside consciousness in order to peek into it, as it were. In other words, since the starting point of empirical science is reflective judgment, it already presupposes the subject-object structure as well as non-reflective consciousness at the most foundational epistemic level. And as alluded to earlier, it is non-reflective consciousness that grounds reflexivity, not vice versa. All of this begs the question: If consciousness is multimodal and has a non-reflective ground, how can we analyze it empirically through scientific instruments? The non-reflectivity of consciousness implies that the moment we try to grasp it through our mind we find an objectified image of our consciousness therein rather than consciousness itself. Hence, reflection or introspection can never grasp the nature of consciousness.

The computational theories of consciousness objectify consciousness twice: first when it conceives consciousness in the mind as an object of scientific investigation, and second when it seeks to demystify it by observing and then theorizing various psycho-physical states, which are but manifestations of consciousness rather than consciousness itself. The conceptual difficulty besetting the empirical approach lies precisely in its inability to see the multimodal structure of consciousness, which persists as a continuum despite its reflective and intersubjective modes. It also won’t help to simply deny this multimodal structure, because any time we try to deny nonreflective consciousness, we are inevitably employing reflective consciousness to do so—which shows, in a way, that the refutation of consciousness as the underlying ground of subjectivity already presupposes its very reality.

Nevertheless, I agree in part with Searle’s definition (or rather description) of consciousness. As Searle says, consciousness is present in all of our mental and intellectual activity, whether it is about playing chess or about arguing politics and philosophy. But consciousness is not merely characterized by a subjective feel, as Searle and other philosophers have argued. Rather, there is an aspect of consciousness that is more basic and foundational than even the subjective irreducibility of consciousness.

Nonmodern traditions affirm the multimodality and multidimensionality of consciousness, with the empirical consciousness of the individual self manifesting only a limited purview of Absolute Consciousness, the divine source of all consciousness. That is, empirical consciousness characterized by a subject-object structure represents only a restricted portion of the individual self, and the latter represents only a tiny part of subtle consciousness, the intermediate-level consciousness between the divine and the human self. Nevertheless, the individual self is not cut off from the global reality of consciousness. What distinguishes the individual self from the rest of the vast, subtle world of consciousness is its own particular tendencies and qualities. Also, consciousness is capable of gradation like light and is similarly refracted in the media with which it comes in contact. In a nutshell, the ego is the form of individual consciousness, not its luminous source, while Absolute Consciousness is infinite and unbounded. One can say that everything in the cosmos is imbued with a consciousness whose alpha and omega is Absolute Consciousness. But if each thing in nature manifests a particular mode of divine consciousness, that implies that even the so-called inanimate objects are alive and conscious in varying degrees. Such a perspective is not to be mistaken with contemporary panpsychism, as expounded by atheist philosophers such as Galen Strawson and Philip Goff, who also argue that consciousness pervades all of reality, including matter.48

Taken together, the above insights on the nature of consciousness refute the idea that consciousness can be replicated in a machine, because whatever is replicated is an objectified image of consciousness rather than consciousness itself. Moreover, the multimodality of consciousness brings out its complex manifestations in various domains of existence that transcend algorithmic patterns.49

Proponents of Dataism propagate a mechanistic and functional definition of intelligence that is similar to their conception of consciousness. For example, John McCarthy defines intelligence as “the computational part of the ability to achieve goals in the world.” Although McCarthy admits that there are various kinds and degrees of intelligence, it essentially involves mechanisms.50 Other popular approaches to intelligence acknowledge its multidimensional characteristics, but still within a functionalist paradigm. For instance, according to psychologist Linda Gottfredson, intelligence is “a very general mental capability that, among other things, involves the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly and learn from experience.… It is not merely book learning, a narrow academic skill, or test-taking smarts. Rather it reflects a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings.”51 One can mention Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences or Goleman’s theory of emotional intelligence in a similar vein, but they all ultimately consider intelligence as a mechanical process limited to its analytic and emotional functions. There is little room to incorporate contemplation or the synthetic power of intelligence, which is self-consciously capable of asking questions related to the meaning and existence of life.52 I broach the discussion of intelligence while discussing consciousness since it is impossible to conceive of thinking (the hallmark of intelligence) without presupposing consciousness. But the prevalent mechanistic-functional approach prevents us from seeing the interconnectedness between all these realities that define human selfhood. Once intelligence is reduced to its analytic functions, there is little room left to see how it is contingent on a moral psychology or purification (tazkiyah) for its growth and perfection. Hence, the Islamic tradition distinguishes between universal and partial intelligence. And a complete theory of human intelligence describes the unfolding of intelligence from potentiality to actuality. It explains the transformation of intelligence from its lowest degree to the highest through a universal agency such as the Active Intellect (the agent intellect responsible for actualizing the potential of the human intellect) and ethical and spiritual lifestyles that shape the function of human intelligence. Human intelligence consists of reason, intuition, understanding, wisdom, moral conscience, and aesthetic judgment in addition to computation. However, in an AI-dominated world, “intelligence” implies only the analytic function of computation. Hence, for the proponents of Dataism, there is no fundamental difference between natural intelligence and artificial intelligence—which is to say we are nothing but a computer and its algorithms! Here this paradigm, which refuses to step outside of its functionalist, machine-oriented approach, reaches a dead end.

Science Fiction or Reality?

If the above reflections on consciousness and human intelligence hold any ground, then we need not fear a dystopian future in which machines substitute for human beings as the most intelligent species on the planet. It also means Dataism’s dream of achieving the Singularity and materializing a transhuman life by uploading the mind to a computer is more grist for science fiction than reality. But this does not mean we should not be worried about the corrosive effect of AI colonialism (defined in terms of control, domination, and manipulation) on human values. Increasingly, people are defining themselves and their lives and aspirations in terms of the achievements of machines, and they do not hesitate to degrade and downgrade their own intelligence vis-à-vis AI.

Moreover, the new ideology of Dataism leaves no room to explore and fulfill the grandest aspirations of humanity, such as truth, love, beauty, and meaning. Invoking a materialistic philosophy of science, Dataism reduces meaning to an emergent aspect of computation. For the proponents of Dataism, science tells us that our reality at a small scale consists of elementary particles whose behavior is described by exact mathematico-physical models. At an elementary level these particles interact and exchange information, and these processes are essentially computational. At this most basic level of description, there is no room for a subjective notion of meaning. But while making all these claims, the beings providing this scientific description of reality conveniently forget that they are conscious beings not reducible to any physical phenomena. It is worth quoting in this connection the great physicist Erwin Schrödinger, who points to the lack of philosophical reflection among science-educated people:

It is certainly not in general the case that by acquiring a good all-round scientific education you so completely satisfy the innate longing for a religious or philosophical stabilization, in face of the vicissitudes of everyday life, as to feel quite happy without anything more. What does happen often is that science suffices to jeopardize popular religious convictions, but not to replace them by anything else. This produces the grotesque phenomenon of scientifically trained, highly competent minds with an unbelievably childlike—undeveloped or atrophied philosophical outlook.53

So, at heart, the problem of AI falls back on the ideological interpretations of science and the scientific method. The authority of science is so pervasive in our culture that since the Enlightenment, we have tended to define human identity and worth in terms of the values of science itself, as if it alone could tell us who we are. But defining the self in only scientific terms tends to obscure other forms of identity, such as one’s labor, social role, or moral and spiritual values. To be sure, we can be described on many levels, from the molecular to the psychological to the spiritual. Science allows us to see ourselves as complex natural, physical objects. But that is barely adequate. For we are subjects of our own experience, intention, thought, and judgment, not just objects. However, in a Google-dominated world, people are increasingly influenced by reductionist and machine-oriented views of self, consciousness, intelligence, and personhood, because the net or AI rarely provides non-modern perspectives on these issues. Which to say, the encroachment of AI colonialism on human values is very real.

But AI colonialism is at work in other ways too. In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Harvard social psychologist and philosopher Shoshana Zuboff argues that we are moving into a new kind of economic order in which a handful of companies collects the big data that we generate and exploits it as raw material for the purpose of making money in ways that are obscure to most people.54 Harari reaches a similar conclusion in 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, asserting that big data algorithms might create digital dictatorships in which all power is concentrated in the hands of a powerful few, while most people suffer not only from exploitation but also from irrelevance.55 The point is that we must warn ourselves of the Faustian bargain: trying to achieve greatness at the expense of our own soul.