Feb 6, 2020

Counting the Minutes

University of Birmingham

Sophia Vasalou’s research focuses on the development of virtue ethics in the Islamic intellectual tradition, with a specialization in Imam al-Ghazālī's work.

More About this Author

University of Birmingham

Sophia Vasalou’s research focuses on the development of virtue ethics in the Islamic intellectual tradition, with a specialization in Imam al-Ghazālī's work.

More About this Author

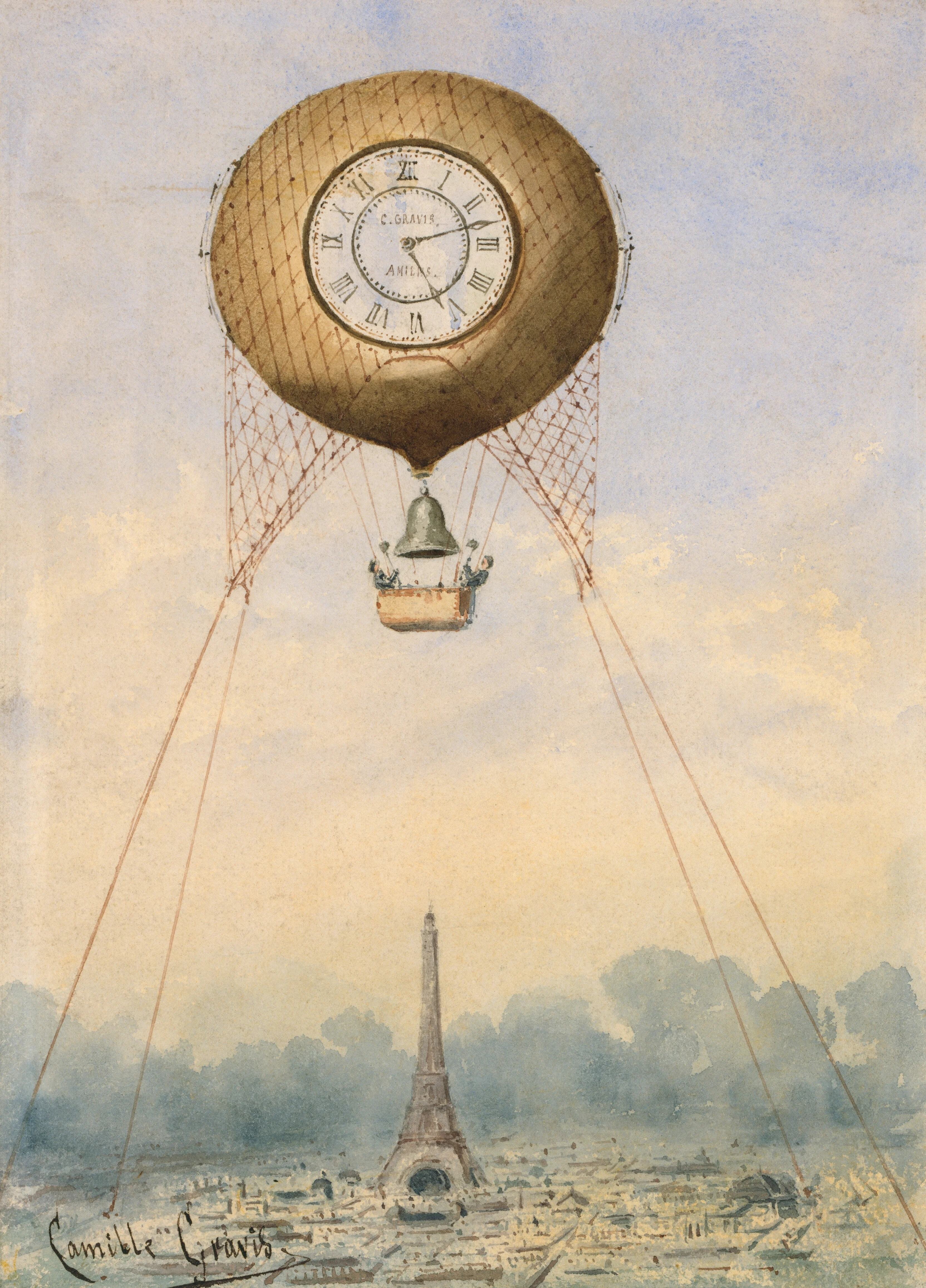

Captive balloon with clock face and bell, Camille Gravis, circa 1889

Since our office is with moments, let us husband them.

It takes a good deal of time to eat or to sleep, or to earn a hundred dollars, and a very little time to entertain a hope and an insight which becomes the light of our life.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Is time experienced differently by different people? In different cultures? Across different places and times? Is there a better and worse way to relate to time? And if we wised up to it, would it revolutionize the way we handle the most basic units of our lives: our minutes, hours, and days?

The answers to some of these questions will seem obvious to us self-conscious moderns, hounded as we are by the tempo of life ceaselessly ratcheted up by wave after wave of technological advances. When the social psychologist Robert Levine published his book The Geography of Time in 1997, against the background of a long string of studies exploring the cultural history of timekeeping, his general insight would not have surprised many readers. Put your feet down at one point on the earth’s surface, and you will find that the pace of life changes dramatically from what you knew it to be at another. Time in Brazil or Burundi is not time in Switzerland or New York. This can be seen by, among other things, comparing the performance of different countries on a number of simple but telling measures, such as how long pedestrians take to cover a distance of sixty feet in downtown areas and how accurate public clocks are.

An important way of describing different temporal cultures is in terms of a distinction between “clock time” and “event time.” Clock time is the type of time we are most familiar with: linear time divided into regular, fixed units and measured through mechanical (and now digital) timepieces. In cultures that follow clock time, the clock is the central cue in deciding when an activity stops and starts (a university lecture, a children’s party, night-time sleep). Cultures that live on event time inherit an older way of thinking about time, which is attuned to the more fluid and organic rhythm of natural events. Even today, farming communities in Burundi are more likely to fix time by reference to natural processes (“when the cows go out to graze,” “almost the morning light,” “when the rooster sings”) than to the standardized time units of our familiar clocks. These different attitudes to time, Levine observes, have a predictable correlation to economic status. The stronger the economy in a given locale, the faster the pace of life, and the greater the dominance of clock time.

Many of us will instantly recognize ourselves from Levine’s sketch as living in a clock-time culture. This culture was made possible by the emergence of increasingly accurate means of measuring time that supplanted the wayward sundials and water clocks of previous eras, with the invention of the pendulum in the sixteenth century marking a watershed moment. Newly controllable, having been granulated into minutes and seconds and their subdivisions, time was then zealously pressed into the service of the ideals of efficiency and productivity that have become a hallmark of modern postindustrial societies and their marketing economies. Time is money—too valuable (in this hard-nosed sense of value) to be wasted.

The eighteenth-century American polymath and political luminary Benjamin Franklin was one of the prophets of the modern attitude to time and the new morality it germinated. Among other moral qualities, the virtue of industry was singled out for special praise across his writings. It was one of the thirteen virtues included in the celebrated program of self-reform that Franklin detailed in his autobiography, and it also came up for special mention in his pseudonymously published Poor Richard’s Almanack. Idleness, doing nothing, offends against the immensity of time’s value, time being “of all Things the most precious.” The maxim of industry as a virtue is about extracting every last shred of value from this precious resource: “Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions.” By “useful” activity, Franklin mainly had economically productive work in mind.

If we’re to understand how great achievements become possible, we need to anatomize how high-achieving people structure their hours and their days.

One of the most interesting expressions of this new morality was a more controlling attitude toward time and its individual units, starting from the basic unit of a day. The partner principle of industry was “order,” and the way Franklin sought to fortify the latter, he explains in his autobiography, was by drawing up in his notebook a clear “scheme of employment for the twenty-four hours of a natural day.” Specific time slots were allocated to specific activities, with continuous blocks earmarked for “work,” interleaved with bands of time dedicated to other activities, such as reading, conversation, music or “diversion,” and washing and having dinner. Franklin’s days would be bookended by two questions: “What good shall I do this day?” (morning) and “What good have I done today?” (reviewing the day in the evening).

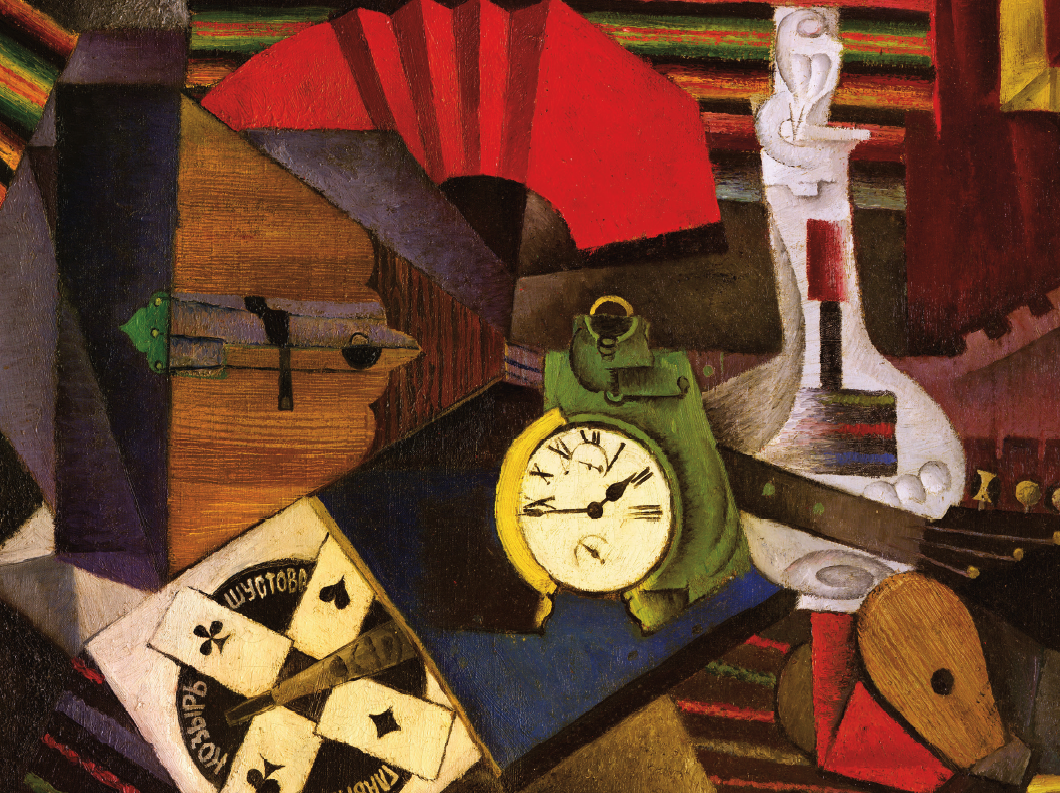

The Alarm Clock, Diego Rivera, 1914

Franklin’s ideal of bustling industry, and the memorable maxims in which he immortalized it, still reverberate in our culture. (“Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise!”) In his highly controlled schedule—itself a textbook example of clock-time rule—we will recognize the kernel of familiar recommendations found in many modern time-management guides. Set goals, schedule your day, the more granular the better. We may also recognize, in the near-voyeuristic interest we take in the personal information divulged by Franklin, the broader fascination we have developed in the private lives and daily routines of others. Mason Currey’s recent book Daily Rituals, which documents the daily routines of successful artists and intellectuals, exemplifies this fascination well, while also pointing to the attitude toward time that underpins it. If we’re to understand how great achievements become possible, we need to anatomize how high-achieving people structure their hours and their days.

Yet while many of the features of Franklin’s model of a well-spent day clearly reflect the specific cultural climate of dawning modernity, whether the same could be said about all of its features is an interesting question. For one, the exercise of starting off and then winding up the day with a moment of quiet reflection on one’s aims (prospective) and one’s success in realizing them (retrospective) evokes a practice that has found a place among many historical schools and thinkers concerned with the “art of living” in its broadest sense. The best-known case is provided by philosophers in the ancient world, such as the Stoics and Epicureans, whose practices have been limpidly documented by the French scholar Pierre Hadot.

In his Meditations, we see the Stoic emperor Marcus Aurelius bracing himself for the day ahead with reminders and self-admonitions: “Say to yourself in the early morning: I shall meet today … treacherous, envious, uncharitable men … . I can neither be harmed by any of them … nor can I be angry with my kinsman.” In the essay On Anger, Seneca describes the exercise of self-examination he carried out at the end of each day and how he would bring himself before his own inner court to stand trial, reviewing everything he had done or said over the course of the day. “Could anything be finer than this habit of sifting through the whole day? Think of the sleep that follows the self-examination!”

More purely than Franklin, Aurelius’s and Seneca’s focus in this before-and-after meditation on the day is not on work in the economically useful sense but on the actualization of moral norms and spiritual ideals. Taken in this sense, analogues of the practice can be found in numerous religious traditions, including Christianity and Islam. Hadot cites, indicatively, the words of the sixth-century Christian monk Dorotheus of Gaza: “We ought not only to examine ourselves every day but also every season, every month, and every week, and ask ourselves: ‘What stage am I at now with regards to the passion by which I was overcome last week?’”

The emphasis on the need to control the day by a deliberate look forward and then a look backward is thus an old one. It is also a very natural one—the natural extension of any endeavor to effect some type of change in our life. How could moral ideals and reflective conceptions of the “art of living” take root in our life unless they were tethered more concretely in the flow of time? It may be that, reading a book one day or listening to a lecture, you discover there’s a new way you’d like to be, to lead your life; you arrive at a new insight about what you’d like your priorities to be. You read some Stoic writer, say, and you’re captivated by the thought of how differently you’d live if you could really take to heart the distinction between what depends on you and what doesn’t. How do you stop this aperçu from evaporating into thin air the moment you shut the book, and ensure it actually changes the way you live in the future? It’s easy to balk at this question, as, on the simplest level, it broaches the fundamental mystery of how people change. But on another level, the answer seems clear. You need to find ways of interacting with this aperçu again, and regularly, in the time that follows, building such interactions into the granular structure of your day, with its concrete succession of minutes and hours.

Thus, even if we acquired the technical capability to measure and fix the minutes and seconds only recently, the drive to control time—to plant hooks on its slippery form—seems a natural corollary of the human aspiration to change. This is also evident from the wider interest taken by many of the thinkers just mentioned in planting such hooks beyond the curtain-rising and curtain-falling moments of the day. The morning and the evening may be opportune moments to regroup. But to really put one’s principles and ideals into practice requires a more ongoing kind of attention to the present moment—a constant watch for occasions that mobilize these principles.

Woman Reading, Edouard Manet, 1879-1880

Yet what about Franklin’s sense of the value of time, of the immorality of wasting it? It is a moral sense that most of us will have imbibed by the time we have grown into fully functioning adults and taken our place in the social world, and for many of us, it will be twinned in our minds with the imperative of productivity and “useful” work. The tyrannical nature of this imperative has provoked countless cultural polemics, especially as our world has sped up with the advent of new technologies. One thinks of recent calls to embrace the Dutch concept of “doing nothing” or the “slow movement,” or of more philosophical critiques of the work ethic and its regnant virtues. This was Bertrand Russell’s aim in his 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness,” where he decried the “immense harm … caused by the belief that work is virtuous” and the instrumental mentality it fostered: “modern man thinks that everything ought to be done for the sake of something else, and never for its own sake.” Russell’s aspiration was instead to “induce good young men to do nothing.”

It is natural to think of this ethic, with its emphasis on the value of time and its productive use, as a distinctively modern phenomenon, and indeed pathology, one deeply tied up with the capitalist economy whose workings it so evidently and marvellously oils. Certainly, one struggles to find similar attitudes to time among Greco-Roman philosophers, even though for many of them reflection on the finitude of life—hence scarcity of time—plays a crucial moral role. We will live differently if we “live each day as if the last,” in Aurelius’s words.

For every hour of our lives, a tradition goes, there is a corresponding vault in the transcendent realm. Each vault can be filled with right actions, filled with wrong actions, or left empty.

Yet it will then be interesting to consider the viewpoint of one important premodern thinker, the eleventh-century Muslim intellectual Abū Ĥāmid al-Ghazālī—not only as a way of pursuing historical questions about how we classify different attitudes to time and chronicle their cultural evolution, but also as a way of pitching the more relevant question of how we ought to relate to time. One of the many grounds of al-Ghazālī’s fame is his attempt to chart an all-inclusive Islamic “art of living” in his magisterial multivolume work The Revival of the Religious Sciences. This is a project he spools out over an eye-watering three thousand pages of printed text, developing his views about what we should believe, how we should act (toward God, toward others), and what we should be like, detailing with special care the qualities of character we should strive for and the qualities of character we should uproot.

If the small matter of three thousand pages is worth underlining, it is because it poses even more sharply the quandary mentioned earlier: reading a book, listening to a lecture, a new way of being flashes before you—how do you stop this aperçu from evaporating into thin air, a mere flash in the pan … ? How do you go from merely admiring the ideas you read on the page to actually living them? An urge to exert control is a natural response, and what must be controlled is time. We will not wonder, then, to find al-Ghazālī, near the very end of the book, offering some guidance that explicitly proposes to tether this ambitious spiritual program in the concrete and granular structure of lived time.

This guidance appears in a volume running under the title On Vigilance and Self-Examination. The title already tells half the story. It is a story about our relationship to time, beginning with the basic unit of a day. Al-Ghazālī’s first set of bookmarks on the day mirrors the ones planted by ancient philosophers: we must begin the day by stamping it with our intentions, and we must end it by surveying the stamp we actually produced. What will seem extraordinary coming from more familiar conceptions of how to bookmark the day is the paradigm al-Ghazālī uses to describe this process. It is a paradigm that belongs to the world of economic activity, and comes complete with the vocabulary of trade, capital, profit, and bookkeeping. No less interesting, it comes with a clear recognition of the logical implications of the idea that we should frame the day through admonition and self-examination. To the extent that we imagine this in performative terms, as an enacted exchange, we must inevitably think of our selves as comprising two different parts: the one that gives admonition and the one that receives it, the one that is examined and the one that does the examining.

Even among Stoic writers (Seneca is a good example), this moment had a specific dramatic character that pointed to these implications. Talking about self-examination, Seneca invokes the paradigm of the court of law, with the person then divided into two dramatis personae: the judge and the arraigned. We are used to thinking of the law as the central paradigm for moral thinking in the Abrahamic religions. Al-Ghazālī may thus defy our expectations. In his dramatization, the two parties are the merchant and his business partner. Rising in the morning, we must put an hour aside to address ourselves, like a merchant instructing his partner about to go out for the day to conduct business, taking a pledge from him about how he will use his assets. “My lifetime is the only stock I possess. Once it’s gone, gone is my capital, and lost is the hope of trading and seeking profit.”

The hoped-for profit is the purification of the soul, which underwrites its salvation. The stock is time. And time is this new day we have been granted, made up of twenty-four hours. For every hour of our lives, a tradition goes, there is a corresponding vault in the transcendent realm. Each vault can be filled with right actions, filled with wrong actions, or left empty. Every hour has potentially salvific value; every second. “Every single breath we draw while we live is an irreplaceable gem, which can be used to purchase a treasure that entails everlasting bliss.” So go forth knowing the true measure of the minute and the hour, and do your best not to waste them and incur a terrible loss. Every evening, you will be called to account for the hours and minutes you have spent.

The attitude of vigilance instilled by this daily covenant, concluded and then audited at the head and foot of the day, finds its complement in the attitude al-Ghazālī urges us to adopt in the moment-by-moment unfolding of the day. At every elapsing moment, there will always be something that it is our duty to do; that it is our duty to avoid; or that, while falling short of duty, it would be better or best for us to do (such as things that benefit our body or mind). The present is simply never neutral. It always contains a normative demand. Our task is to identify this claim and then fulfill it. Hence, the present moment must always have the character of striving (jihad). Striving in this moment, we need to live it as if it were our last.

Were we to look for the origins of al-Ghazālī’s economic paradigm for thinking about time, we would no doubt find some of its most important roots in the language of the Qur’an. In a well-known verse, God is described as having “purchased” from believers their lives and their possessions in return for paradise (9:111). This is God’s covenant with humankind, which one’s daily covenant with oneself (the higher part of the self addressing the lower) essentially recapitulates. The Qur’an is also rife with references to profitable and ruinous transactions, warning against the foolishness of buying “the present life at the price of the world to come” (2:86). Lurking here, should one care to look for it, is an idea of human dignity. Those who buy this world at the cost of the next sell themselves short, or cheap: they owed themselves better.

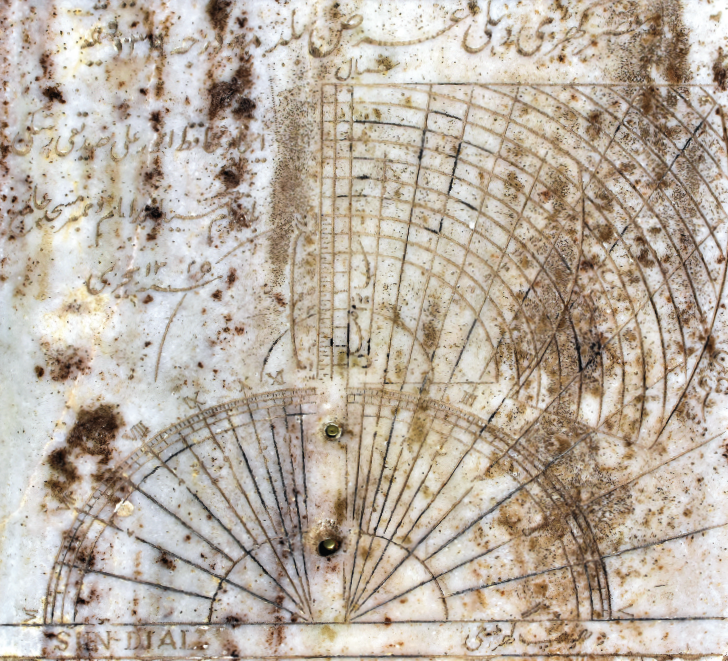

A sundial in the Jama Masjid, Delhi, India; photo: Graham Beards

The question of origins is a relevant one if we’re interested in gaining a fuller understanding of what shapes conceptions of time in different cultures. Yet putting this question to one side here, many things may strike us as remarkable in the picture of time that flows from the economic paradigm al-Ghazālī employs. On one level, al-Ghazālī’s way of thinking about time will seem remarkably, almost uncannily, familiar. This includes, above all, his view of time as a quantifiable commodity we should put to the most productive possible use and jealously guard against waste. Benjamin Franklin, we may speculate, would have found much to admire in this attitude, in al-Ghazālī’s strictures against idleness and his emphasis on maximal productivity. Al-Ghazālī’s metaphor of transcendent “vaults” that we can—and should—diligently keep filling crystallizes this emphasis especially clearly.

Al-Ghazālī’s attitude, to be sure, is not an exemplar of modern clock time in the familiar sense, where the clock dictates the rhythm or duration of events. Al-Ghazālī is not interested in how activities should be scheduled. He presupposes only the more basic understanding of time as composed of a number of countable units, with the hour the chief such unit. Yet these are isolable units, it’s important to note, that register as being objectively “out there”—actually existing containers capable of being filled in different ways. The metaphor of “vaults” again encapsulates this idea clearly, though here one might also credit the timekeeping technologies of al-Ghazālī’s day for making certain ideas more thinkable. While the famous water clock installed at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, a lodestone for historians old and new, was built after al-Ghazālī’s lifetime, water clocks were constructed in the Islamic world from early Abbasid times, and there was a public clock at the Umayyad Mosque from at least the tenth century, which marked the passage of the hours in rather baroque fashion. The idea that time can be broken down into units whose beginning and end may be objectively determined (however imprecisely) thus reflects the timekeeping practices of al-Ghazālī’s era.

The act of sitting down to the table to eat can become a moment of contemplative expansion as we bring a meditative wonder to bear on it and our thought follows a movement upward from the created order to the Creator.

Yet whatever differences may separate our relationship to the clock from al-Ghazālī’s, another contrast may strike us more strongly. Because while al-Ghazālī’s views about the productive use of time may seem uncannily close to home, his idea of what productive means, or what the relevant product consists of, will be far less so. When self-help books on time management take us by the ear to show us how to “get more done,” they certainly don’t mean how to get more good deeds done or how to acquire a greater number of virtues, as al-Ghazālī appears to suggest. They’re not thinking of a “moral” product but, above all, of work in the garden-variety sense—Benjamin Franklin’s and Bertrand Russell’s sense—in addition to the other non-work activities we have to juggle in everyday life (quality time with friends and family, our weekly quota of physical activity, and so on).

The idea that we should seek to maximize our moral performance might thus make us bristle. Modern moral philosophers, in particular, have had much to say against the demanding model of morality that al-Ghazālī presents. At every moment, there’s some normative demand for us to meet; all space is moral space, all time a time to be moral. We may term this, kindly, a “principle of moral plenitude.” Less kindly, we might consider it a form of moral totalitarianism. Either way, this is a morality that simply asks too much.

Yet first of all, and to get some of the facts straight, the word moral does not quite get at al-Ghazālī’s concern. There are many reasons for this, but one of the most important is that the activities al-Ghazālī thinks of as populating normative space aren’t confined to that narrow class we would comfortably identify as moral, such as visiting the sick or volunteering at soup kitchens. He’s not thinking of us as casting about all day for something virtuous to do, paragons of a bustling goody-two-shoes morality. The activities that al-Ghazālī thinks are demanded of us include the contemplation of nature (taken as a divine creation) and the study of enlightening books, religious and otherwise. It also includes activities we would call moral in a more generous sense: the pursuit of ways of bettering the self.

With this broadened understanding of the range of values al-Ghazālī is promoting, his account of how we should relate to time may now appear in a different light. Buried beneath the crusty exterior of his totalizing principle, we may be able to discern a rather more seductive idea—an idea that arguably explains why such a principle might appeal to someone in the first place. Call it the “principle of evaluative plenitude.” It’s the idea that every single thing we do, every moment of waking awareness, every instant of our lives, might carry value, be significant, be ordered to some meaningful end. No moment need be lived in vain, with nothing to show for it; there is value—service—to be extracted from every instant of experience.

A further brush-stroke to al-Ghazālī’s picture crystallizes this possibility a little more clearly by playing down the emphasis on quantifiable performances. It’s not simply about moving through time with the aim of accruing the largest possible number of distinct actions bearing some special normative stamp (“make a charitable donation,” “perform an act of humility,” “meditate on scripture,” “pray”). It’s also about changing our relationship to the activities we normally pursue, including the most ordinary and mundane. With the right turn of attention, there is no act that cannot become significant. The act of sitting down to the table to eat can become a moment of contemplative expansion as we bring a meditative wonder to bear on it and our thought follows a movement upward from the created order to the Creator. The way we sit or sleep or even go to the toilet can be transfigured through the type of spiritual vigilance al-Ghazālī advocates—ultimately a kind of God-consciousness in which our consciousness is remolded by our awareness of God’s. There are more significant ways to be sitting or standing, lying down and straightening up. Every action, even the simplest, can become a devotion. Spiritual value can be extracted from everything we do.

Al-Ghazālī’s picture of a well-lived day is thus the picture of a life bursting at the seams with value. His exemplar moves forward through time with a ferocious sense of mission, intent to press every instant into the service to which it is called. Commenting on the concept of human selfhood, the American philosopher Josiah Royce suggested that the purposes we pursue form the foundation of our self: “I cannot answer the question ‘Who am I?’ except in terms of some sort of statement of the plans and purposes of my life.” Hence, “a person, an individual self, may be defined as a human life lived according to a plan.” This plan, Royce emphasized, must be characterized by a strong degree of unity, as otherwise we remain “a cauldron of seething and bubbling efforts to be somebody, a cauldron which boils dry when life ends.” A self is thus a life that has a single purpose running through it—a single loyalty. In many ways, al-Ghazālī provides us with a consummate expression of selfhood as Royce conceptualizes it. While “planning” in the more familiar sense holds no interest for him, the Ghazālīan agent faces the day with a unity of purpose, and a passionate drive to achieve it, second to none.

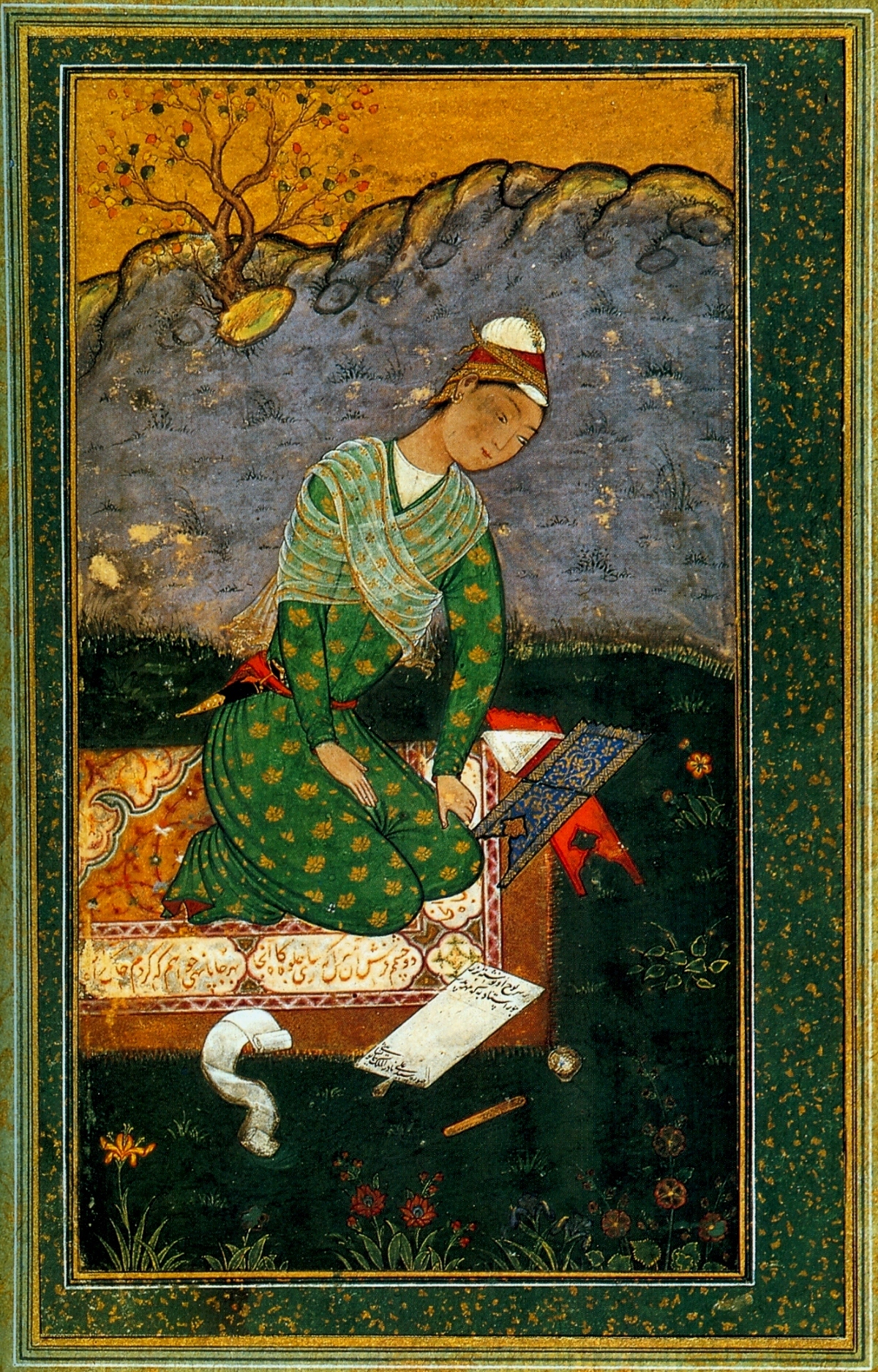

Portrait of a young writer, Mir Sayyid Ali, 1550

Yet of course this raises a question that has already been in the wings. We may be able to admire this drive and the sturdy sense of self it secures, and we may also be able to daydream what it would be like to live in the evaluative universe that supports it, in which every moment has a definite service and vocation to which it is called. What Royce describes philosophically as a condition for being a coherent self also, after all, corresponds to a psychological need that many of us will recognize from actual experience. Few if any of us relish “seething and bubbling” to no effect, and many of us long to find a clear purpose that will give a fundamental order to our lives—a loyalty capable of commanding our complete devotion. Royce’s codicil that the very act of searching for purpose may constitute a unified purpose in its own right will seem like cold comfort to those who feel they have not yet succeeded in this quest—a rather abstract kind of consolation prize. The same constituency may wonder what use there is in holding up a splendid image of what it would be like to live life with an all-encompassing sense of significance that transforms our attitude to time, if this is not a genuine possibility for us. Al-Ghazālī’s conception of time, and of the vocation of individual moments, ultimately takes its meaning from a particular type of worldview with deeply religious foundations. If those who do not share this worldview allow themselves to enter into the attractiveness of the conception that al-Ghazālī unfolds, they will simply be dreaming a dream that does not belong to them. What then is the utility of pausing to engage with this conception at any length? How could it possibly help us tackle the question of “how we ought to relate to time,” as I suggested earlier?

Questions of “utility” are never easy to answer, even for texts and thinkers with whom we may feel a more immediate sense of community. What do I “gain,” for example, from reading the French essayist Michel de Montaigne’s response to the deeply familiar lament “I haven’t done a thing today”? “Why! Have you not lived? That is not only the most basic of your employments, it is the most glorious.” The meaning of this response is not written on its sleeve, of course; by “living,” Montaigne does not mean existing in the biological sense. He means living well, or fittingly, imparting “order and tranquillity” to the conduct of our life. This type of achievement is far greater, Montaigne insists, than those things we traditionally view as achievements: waging wars, building cities, amassing wealth. Taking in this viewpoint, I make no direct gain; my life does not change in the instant. But one can only hope that I now have available to me a new idea that might, when the time is right, bear fruit and help me criticize the ends I pursue and the yardsticks I use to measure myself and my “performance.”

On one level, the fruitfulness of engaging with al-Ghazālī’s understanding of time can be framed in directly analogous terms. Like Montaigne, he provides us with a stimulus for critically reflecting on how we understand the concept of an achievement. In this, al-Ghazālī is certainly not unique. Uniqueness or originality does not determine the value of a point of view, but if we wished to locate the special interest of al-Ghazālī’s outlook and its more distinctive edge as a tool for critical reflection, we might find it in his deployment of a language so intimately familiar to us to make an otherwise so unfamiliar point. Al-Ghazālī’s peculiarly modern appeal to time as a quantifiable resource that may entail profit or loss and his emphasis on productivity and warnings against waste are combined, as I noted earlier, with a very different conception of what productivity might mean. Perhaps if I woke up in the morning, and thinking ahead to the achievements that would make this day seem well-spent, I replaced my habitual metrics with a different type of list—setting goals for kindness or gratitude, for the cultivation and improvement of friendships or the exercise of my reflective and appreciative capacities—my life would go better for me. I might be able to say at the end of the day, with the Stoics, “I have lived,” instead of being anxious to wake up again the next morning to start the Sisyphean cycle all over. Having been shaped by a culture where everything that counts must be capable of being counted, perhaps instead of trying to get myself to stop counting, I simply need to change what I count.

Such a way of answering the question “What use?” may take us some of the way and explain why we might not be worse off for entering into the conception that al-Ghazālī unfolds, even in the absence of a commitment to its founding worldview. It will only be part of the way, since none of the ways in which we fill such an alternative to-do list will ever have the urgency and definiteness of the Ghazālīan agent’s. And certainly it won’t take us to the “dreamy” world structured by the principle of evaluative plenitude, where every instant of time has a valued vocation. Yet we sometimes find a viewpoint useful not because it helps us change how we act or think (as I just suggested), but because it simply helps us see ourselves more clearly. Knowing another may be the best means of getting to know ourselves. And for this, even dreaming another person’s dream can be useful.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy