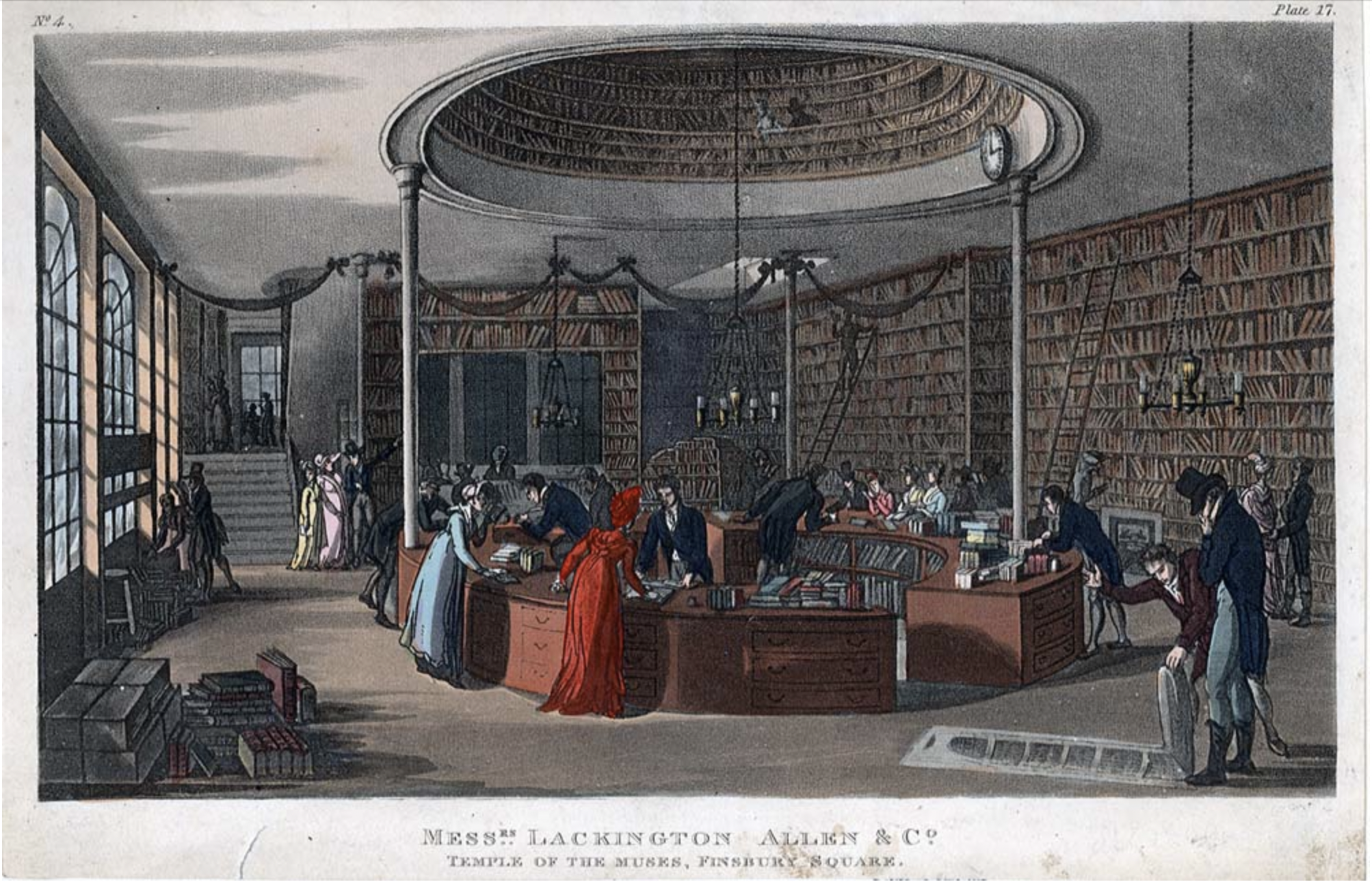

Interior view of the Jones & Co bookstore in Finsbury Square, London known as "Temple of the Muses," engraved by William Wallis c. 1828

Penetrating the poetry and religious life of a past era is a challenge. The vast soundscape of Victorian religious discourse often falls flat on modern ears. Added to this, it’s easy, and fairly commonplace, to dismiss much of this period’s literature as imperial, to assume that it’s not worthwhile to read the works of writers who lived at the heart and height of the British Empire. I’d like to challenge that assumption and suggest that poetry from this period often exhibited a courteousness we can learn from—a sensitivity in its handling of the myriad influences coming out of empire because its citizens routinely met with religious differences at home.

Still, even as a Victorian scholar, when I lately reached for The Death of Œnone, Akbar’s Dream, and Other Poems (1892) by the British Poet Laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), I questioned how well I would be able to interpret its design and Tennyson’s intentions. As his final collection, the volume occupies a unique position in his oeuvre. Tennyson revised its contents five times before his death, just managing to see it through the press in his final weeks. It distills and embodies his lifelong grappling with religion. “Akbar’s Dream” is the fifth of twenty-three poems in the collection, and its inclusion in the title indicates its prominent position in the volume.

“Akbar’s Dream” speaks to questions of religious tolerance, to the complex images of Indian history and Eastern religions in Victorian imaginations, to Akbar’s (and Tennyson’s) Persian Sufi influences, and to a much wider project of growing religious awareness unfolding in Victorian Britain in the late 1800s.1 To my mind, it raises questions: What should be our comportment during interreligious dialogue? How can we practice civility and tolerance in a way that nurtures syncretic dialogue and porous exchange? What might poetry from an imperial moment in history offer us in a postcolonial-aware era?

The poetry of another Victorian poet, Edwin Arnold (1832–1904), is also worth considering alongside Tennyson’s “Akbar’s Dream.” The influential Arnold worked hard to draw the religious peripheries of empire into the mainstream in Britain. Arnold may not have always succeeded in accuracy where non-Christian religions were concerned, but he did seek to bring about more civility in interreligious matters and to instruct his readers on how to approach and accept religious differences with composure. Poetry in the Victorian period was a particularly potent medium for efforts of this kind. It could set unfamiliar histories and beliefs into familiar stanzas, meters, and rhymes. Today, as readers, we are often unused to navigating poetry but, by examining poetic works, we impose on ourselves slower reading practices and opportunities for careful attention to context and intention.

“Akbar’s Dream”

Tennyson had little patience for displays of religious intolerance. He stood by his friend, the theologian F. D. Maurice (1805–1872), when he was dismissed as chair of theology at King’s College, London, for his unorthodox views.2 For decades, Tennyson remained close with Benjamin Jowett (1817–1893), a cleric and classicist, who similarly jostled up against the abrasive fronts of Anglican orthodoxy.3 Jowett fed Tennyson ideas for his poems throughout their friendship. Toward the end of their careers, he nourished Tennyson on a steady diet of comparative religion, what was then a new and developing enterprise seeking to produce a systematic account of the growth and nature of religious belief around the world and through the ages. The phrase “unity in diversity” served as comparative religion’s central maxim, and one historic figure in particular rose to prominence in the minds of comparative religionists: the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1542–1605), who ruled most of the Indian subcontinent from 1556 to 1605.

Akbar believed that the diverse religions across his empire—Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity among them—should be respected and interrogated in a spirit of tolerant curiosity. He famously held a court at Fatehpur Sikri in which different religious viewpoints could be expressed. By 1582, Akbar began to promote what was called Tawĥīd-i Ilāhī, or “Oneness of God,” which is now referred to as Dīn-i Ilāhī, or “the Divine Faith.”4 Grounded largely in esoterism and belief in divine monotheism, it was nevertheless an eclectic selection of what Akbar considered the best concepts and rituals from every religion. Victorian audiences interpreted it as an admirable attempt to simultaneously acknowledge and transcend religious differences. When Jowett brought the history of Akbar to Tennyson’s attention, Tennyson became enraptured with Akbar’s example of religious liberalism—from Akbar’s rejection of religious persecution as a political ploy to his civility toward practitioners of diverse religions. Moved by the significance of Akbar’s example, Tennyson sought to bring the historical context, religious import, and spiritual atmosphere of Akbar’s reign to the page in verse.