Aug 21, 2023

Dignity Is for the Heart, Not the Ego

College of the Holy Cross

Caner K. Dagli is an associate professor of religious studies at College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

More About this Author

College of the Holy Cross

Caner K. Dagli is an associate professor of religious studies at College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

More About this Author

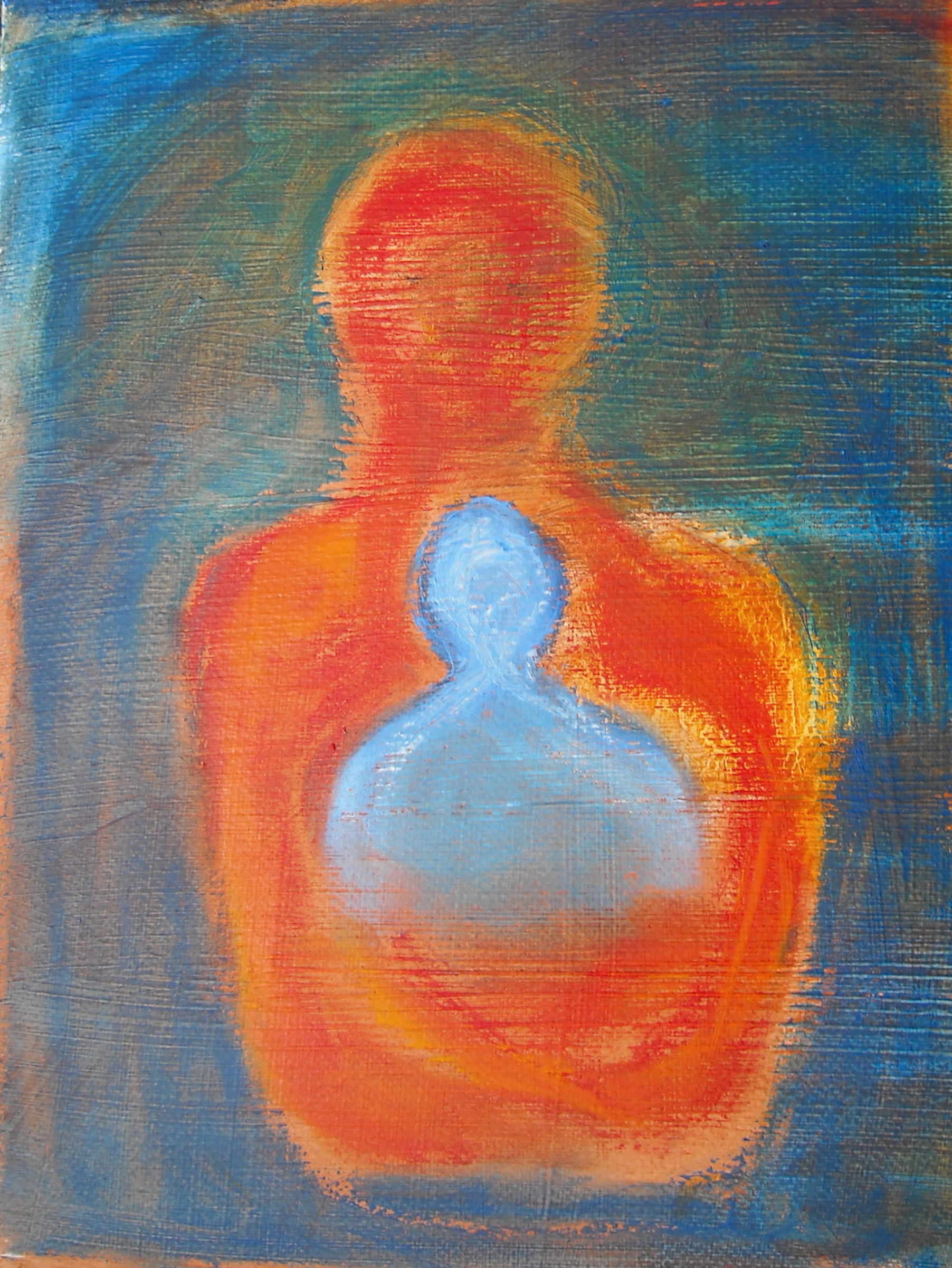

Split Face, Laura Summer, 2020

In The Alchemy of Happiness, Imam al-Ghazālī (d.1111) describes the heart (the spiritual heart, not the bodily organ) as a sovereign who is enthroned in a capital city (the body) and governs through his vizier (reason), his standard-bearer (desire), his superintendent (anger), and his spies (faculties of perception), as well as through his memory, imagination, and other faculties. When this sovereign heart does not direct its inner and outer subjects from its proper place, al-Ghazālī says, the city falls into disarray and ruin. Although human beings have bodies and live in the world, the heart has an angelic nature, exists at the level of the spirit, and has windows that can open onto divine mysteries. The heart is the “I” and the ego is the “self” in the sentence “I disciplined myself.” The heart is what is aware when one is self-aware; it awakens when one stops sleepwalking through life. It brings attention inward from the outward.

Dignity is one dimension of the proper relationship between that heart and the ego. Dignity is my self-mastery in your presence, my self-mastery as experienced by you, and your self-mastery as experienced by me. To have dignity, to demand dignity, and to treat others with dignity are three aspects of the same virtue of restraining the selfish passions. We owe that aspect of spiritual discipline simultaneously to ourselves and to others, and others owe it to us. To act with dignity is to demonstrate not merely ethical behavior, but ethical behavior insofar as such actions are intelligible as a heart mastering the passions and desires that constitute an ego. This means that ultimately there can be no dignity without spirituality and no spirituality without dignity.

The three dimensions of self-mastery presuppose and imply each other. To act with dignity means both to treat others with dignity and to resist the indignities inflicted by others upon oneself. As a form of self-mastery, dignity is immediately charitable and socially aware, because the beauty of a human being mastering the self necessarily leads to the beauty of treating others with dignity as well as the expectation to be treated with dignity by others. Whether one treats another with dignity must be measured against that person’s spiritual heart, not his passions or desires. To rob someone else of dignity, understood in this way, really means to target another’s heart and side with their fears, despair, greed, and vanity until the heart’s place in the soul is toppled. Every human being has a limit to the deprivation, infliction of pain, and insults that he can sustain. Let us remember that the ego can win its battle with the heart with help from the outside in different ways. The Prophet Muhammad s once even forbade insulting a man who was found drunk, saying, “Do not speak thus—do not help Satan against your brother” (Śaĥīĥ al-Bukhārī 6395). To wrong others—to rob them of dignity—is an intrusion upon their hearts, and extreme cases of trespass can bring human beings to a state of bare survival, vulnerability, and hopelessness such that their natural impulses almost necessarily take over. Being placed in a situation that favors the ego to such an extent that one struggles to be more than an animalistic stimulus-response machine feels like an inability to fulfill one’s purpose and to be in control of oneself; thus one experiences a loss of dignity even if one is excused and forgiven in the eyes of God.

Being afraid, hungry, insulted, lonely—these conditions take the energy of the true self away from fulfilling its transcendent purposes. Extreme fear, grief, despair, and loss tax the body and soul and trap the heart in a waking nightmare. Injustice and oppression are tantamount to robbing human beings of their dignity—pushing the hearts of others to the point of losing their ability to be masters of their own egos. Therefore, to treat others with dignity requires that one neither deprive nor frighten them, not be indifferent to their deprivation or fear, and to neither cause them grief nor trap them in loneliness and hopelessness. It does no good to say to someone, “Be dignified no matter the circumstances!” “Be a saint!” is not realistic counsel, although it is a good ideal. The loss of dignity is not something that can be imposed directly from the outside, and rare individuals can remain dignified in the most extreme situations, but outside injustice undermines dignity because it removes the air that allows one’s personal dignity to breathe.

***

Dignity is thus both personal and social simultaneously—whether one recognizes this truth or not. By remembering that human beings are not only a bundle of passions and interests, one can use the ordinary and everyday meanings of dignity and dignified but understand them against a larger and deeper picture of what makes human beings what they are. Unfortunately, in today’s public discourse—liberal and legal discourse since the mid-twentieth century—dignity has become a mysterious substance that inheres equally in all the Darwinian biological machines that we call Homo sapiens, such that one says that all people “are equal in dignity” or “have inherent dignity.” Such uses of dignity as a grounding for rights or as a principle of equality only exist in specialized and quasi-official contexts—like “beverage” or “boarding process.” They constitute an escape from plain language and sincerity and, like corporate jargon or legalese or science speak, announce a certain set of rules about what to think and how to talk.

Once upon a time, dignity denoted rank or prestige, but this now archaic use—as opposed to “being dignified” or “maintaining one’s dignity”—has mostly fallen away except when it comes to statements such as those found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other philosophical and legal contexts. No one ever asserts that people are of unequal dignity with respect to anything; so what then is the meaning or point of demanding a belief in equal dignity? When most people speak today of dignity, they mean a way of being and comportment, with no thought about the now-outdated meanings mentioned above.

Yet dignity is not something one simply has (like brown eyes or vital organs) but something that everyone must do. One must be careful with figurative language like “respecting dignity,” because dignity is that very showing of respect. When one addresses one’s spouse as “my love,” one really means “my beloved.” It would be strange to invent some entity called “belovedness” (or even simply “love”) that inheres in other people and which is the thing that one cares for. But that is what has become of dignity in phrases such as “inherent dignity.” One cannot have respect for dignity any more than one can have compassion for love. One could say we owe our own dignity to others, or that everyone is owed dignity (i.e., dignified behavior). That would be closer to its real use. “Love thine enemy” is a fine maxim, but it is a clear statement of virtue or duty, and no one would confuse it with the notion that somehow everyone deserves the same love. It’s the same with dignity. Only people who fail to understand what love is can say, “All people are equal in belovedness” or “One should love everyone’s belovedness.”

***

“Injustice and oppression are tantamount to robbing human beings of their dignity—pushing the hearts of others to the point of losing their ability to be masters of their own egos.”

A better alternative to saying, “All human beings have equal dignity,” is to say, “All human beings are sacred,” meaning they are inviolable because of their relationship with the Absolute, the Infinite, the Transcendent. At least sacred means something to most people, and as a blank placeholder (which is all “dignity” is now in such contexts) it works just as well. Even if the word “sacred” is ambiguous—it can refer to anything that is deeply important in a nonnegotiable way—it is still much less plastic and vacuous than dignity has become, so much so that some philosophers and medical ethicists have long rebelled against its use. To say that human beings are all sacred involves no quasi-official redefinition of the word. The proclamation, “All these are sacred,” hardly requires mentioning that they are all equal, valuable, and inviolable.

But what are human beings such that they are all sacred? What is it that obliges us to treat others with dignity? What is that being that possesses a heart that masters its ego? The metaphysics is important. Unless we believe concretely that each individual has a soul or heart or spirit—a mysterious self that lies as a potentiality within—then all talk of dignity is a pure demand devoid of an account that makes it make sense. Rather than adopting the naked imperative to believe that all human beings have equal value (a fine imperative but one that makes no sense if we are what the Darwinians say we are), it is wiser to acknowledge that it is only through recognizing the vast differences between individual human beings that one can actually grasp what makes them equal. The equality specific to human beings is not some imputed sameness but a principle of differentiation—the potentiality for the realization of the human virtues that manifests when the heart and the ego are in a correct relationship with each other. That potentiality, which the Qur’an calls the fiţrah, is equal in all of us, but it is never equally realized. Dignity (like any virtue) is not inherent in all human beings any more than love or compassion or courage are, but its potential is equally possessed by all. Indeed, dignity is precisely something that people always possess unequally—but these days we are trapped in an official discourse that compels us to take a concept that evokes hierarchy and use it as a marker of sameness.

In much of the modern literature about dignity we encounter a strong resistance to understanding dignity as having to do with human beings’ spiritual nature. Any position that goes against the Darwinian view of human beings is seen as relying on an “internal kernel,” which philosophers such as Michael Rosen reject because it involves “wider, metaphysical commitments that (to put it mildly) not everyone will accept”—as if everyone accepts the Darwinian metaphysics implicit in so much of the dignity discourse today, and as if Rosen and authors like him were not operating within their own metaphysics. People who generally treat metaphysics as something fairly disreputable or old-fashioned suddenly become metaphysicians themselves when their scientism is called into question (and only then). It would seem we are obligated to treat Darwinism as common sense: “metaphysics for me, not for thee.”

In fact, dignity as jargon has become a euphemism for denying a certain metaphysics. It demands a recognition of something sacred about human beings while remaining incapable of describing what that means because it forbids any departure from the Darwinian picture. We are told to believe that all human beings are “equal in dignity,” but we are given absolutely no explanation of why these beings have this attribute of dignity. It is one thing to demand something, no matter how laudable, and quite another to make it make sense.

We want to say that people are equal but do not want to acknowledge that what makes human beings equal is that very spiritual nature that we now deny them. We want to say that people have autonomy while denying that which makes them autonomous. The Darwinian picture—the unshakable horizon for the dominant discourse about “dignity” today—is precisely what makes human beings unequal and unfree. Think about it: Since human beings are unequal along every biological parameter one can imagine, how can a belief in purely biological human beings give rise to the belief that they are purely equal? Let us abandon Darwinian metaphysics and then we can talk about equality and freedom.

That’s why dignity—not the visceral dignity we all experience to greater and lesser degrees, but the quasi-official one—remains ambiguous and generates endless ruminations about its true nature. The literature is voluminous and never-ending; ambiguity almost seems to be the point. If the demand to recognize equal dignity made sense in light of what human beings are and are capable of (for example, the virtue of dignity), then society would have reached a consensus on how to understand it. But that common understanding will never come so long as the Darwinian view of human beings as nothing other than mechanical bundles of passions remains absolute.

Let us return to the question of self-mastery. The problem with erasing the heart from view is that the place of the heart does not just go away; a part of the ego takes up residence. When we dislodge the heart from its proper seat upon its throne, its role will be usurped by some aspect of the ego—greed, lust, ambition, pride, vanity. Dignity will no longer be experienced as the mastery of the ego by the heart, but instead by how well indulged that particular passion is.

“The Darwinian picture—the unshakable horizon for the dominant discourse about “dignity” today—is precisely what makes human beings unequal and unfree.”

Sometimes, religious thinkers will draw a distinction between freedom from the world and freedom in the world, but the true difference is between freedom of the heart and its enslavement to one or another pull of the ego. For human beings to have dignity, the true self (the heart) must remain on the throne at the center of their being, and no part of the ego (the passions) can be allowed to take its place as monarch over the other passions. The modern world can only ask us to barter one passion for another. One can make demands about “inherent dignity” and “equal in dignity” but one can never dignify egotism by promoting one part of the ego above the other parts. One does not fulfill human purpose—a condition of dignity—but only this or that human desire.

When we talk about dignity in terms of autonomy and freedom, freedom really means an indulgence of one part of the ego. If we talk about dignity as equality, we must ask: Which parameter (among many possibilities) is equal? We cannot all be equal; the equality, the sameness, has to be equality in something. A transgender ideologue would not find dignity in a life that affords economic flourishing for all but denies freedom of expression and sexuality. A free-market fundamentalist would not find dignity in a world of sexual hedonism that also forces everyone into government housing and puts caps on income. Capitalists find dignity in one form of egotism, communists in another, liberals in another, and nationalists in yet another. These ideological conceptions of dignity are all forms of egotism, and individuals have dignity in spite of such ideologies, not because of them.

There can be no equality at the level of interests or passions because everyone has different interests and passions that might change on different days. A man at twenty feels happy about a very different set of things than he feels happy about at fifty. In what respect is the younger self equal to the older self, if only the passions and the interests are involved?

Figure #10, Laura Summer, 2010

A man in European democracies has tremendous freedom to be promiscuous but has almost no say over his children’s education and can expect to be offered state-assisted suicide rather than becoming a burden to his children when he is old and frail. Very few people in the Islamic world would consider even the most materially well-appointed life under those conditions to be dignified or even free. Ukrainian men today are forced to remain in their country to fight, while women are allowed to depart to other countries. If equality is the basis of dignity, do Ukrainian men have it? Whatever those Ukrainian men have, it is certainly not equality. It reminds us that there is no freedom and autonomy as such, but only this or that kind of autonomy and freedom, depending on which particular passion is allowed to rule the soul.

***

An image might make this clearer. Stained-glass windows, such as those in the great mosques of Istanbul, have intricate combinations of colors in unique arrangements. The pieces of glass and their shapes and sizes are different, and the luminosity coming through them varies from window to window, and even the same window varies from hour to hour. Likewise, the luminous heart at the center of every human being is not present in the same way at all times; even in the same person, the light varies with the flow of time. But the potential for light to shine through is always there, and when the light comes through it fills the space all the same. Stained-glass windows can be equally transparent and the light that comes through them might be the same, but the pieces of glass as glass are of different sizes and shapes and colors. The varied pieces of glass can never be equal, and therefore we should never assert that all windows are equally red (if redness is the favored color) or equally blue or equally yellow or attempt to reshape or disfigure them, thereby denying the windows their purpose as a way for light to enter while also destroying and denaturing the balance of colors as they should be. No window generates its own light and no ego produces its own dignity.

Looking at things this way enables us to connect what we already know about dignity to what we already know about ourselves. It is an affront to human intelligence and morality to demand that we regard a saint and a human trafficker as having equal dignity. People can spot dignity as readily as they can apprehend beauty; they can be inspired by its presence and seek to emulate it. Does it make any sense to be inspired by or to emulate a quality we already possess in exactly the same measure as a hero we admire? Dear reader, refuse to obey the imperative to believe that everyone equally possesses a chimerical quality, an imperative that always comes bundled with the contradictory command to believe that we are nothing but biological machines. Believe instead that each human being is an always-sacred entity that can be either angelic or demonic depending on whether he or she lives in that heart whose windows open onto the divine mysteries as al-Ghazālī said, or chooses to obey the ego and to never fulfill the true purpose of this fleeting but consequential life.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy