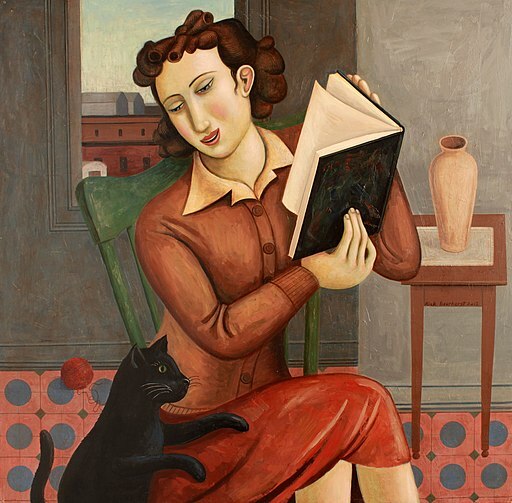

The Distracted Reader, Rick&Brenda Beerhorst, 2013

We all feel distracted, continually dragged aside to other things. We are often too distracted even to pay attention to loved ones sitting right in front of us. How then can we hope to discern carefully our place in this world, and what we are called to be in God’s eyes?

One of the early lessons in the monastery involves the sin of curiosity, a lesson that sounds confusing enough, even to us in an academic and properly curious monastery, that we tend to use the Latin form for it, curiositas. The best English translation is “being nosy,” though that is metaphorical and is a bit silly. But for my own Cistercian tradition, wanting always to know what’s going on around the corner, what the other monks are doing, who’s walking by the window, what that guy is eating, what the odd noise over there is, not to speak of the boundless realm of news and comment one might feel the need to know, all this interest, for all its seeming innocence, seems a sign of having lost touch with the real goal of the moment and of the whole quest: to know yourself and seek God. We can’t afford to be among those who, St. Paul says, “walk in idleness, not busy at work, but busybodies” (see 2 Thessalonians 3:6–12). Full of action—walking, busy—but not getting anywhere. Distracted.

Attention and distraction are not easy to define. Although we might think of distraction as what comes from outside to draw us away from attention, the monastic notion of curiositas suggests that the tendency to succumb to the outer distraction arises from an inner distraction: a lack of contact with, or even a resigned frustration with, the real spiritual work. And then, that real attention the monks aim for is not merely for the sake of efficiency in tasks, though that is part of it. Attention is not simple mindfulness practice—the attentive observation, in stillness of judgment, of the arising and departing of mental states for the sake of attaining greater skillfulness of mind—though this sort of attention to self seems to be an important part of the quest. And again, attentiveness is as much a social grace as an academic skill (think of the attentive host) and the depth of its meaning seems to reach toward the perfection of the spiritual life in prayer. After all, how hard it can be to pay attention at the service, at prayer! This difficulty remains an important challenge for most religious people. We are religious, we believe, so why can’t we keep ourselves from getting distracted? In some way prayer configures itself simply as a form of attention rather than distraction. Yet, if we paid absolute attention to the mystery we celebrate when we serve in the presence of God, if we achieved perfect attention and really engaged with total fullness… would we even survive? The Lord tells Moses, “You shall not be able to see My face, for no human can see Me and live” (Exodus 33:20). Our distraction from the fullness of things might also just concern our being here in this world still. Thus, perhaps the problem of attention is not just about my cell phone; it is about our human condition as temporal and as fallen beings. Prayer in this life is not so much “paying attention” as continually and repeatedly returning to attention, a steady practice of turning back to that which matters most.

Of course we are drawn to other things—we are with friends having fun, but suddenly everyone at the table is busy texting. And yes, we should be somewhat ashamed of it. At the same time, isn’t our soul designed to pay attention to many things, to be drawn to interesting and delightful matters? Marking this capacity as central to his work, the poet Dante creates a dialogue in the middle of his Purgatorio in which he is taught about God’s creation of the soul. The character Marco Lombardo speaks:

Issuing from His hands, the soul—on which

He thought with love before creating it—

is like a child who weeps and laughs in sport;

that soul is simple, unaware; but since

a joyful Maker gave it motion, it

turns willingly to things that bring delight. (Purg. 16.85–90)

This soul, a child of God’s joy, rejoices in whatever comes toward it bringing delight, and we should occasionally pause to remember how beautiful this is—how young, agile, and terribly distractable the soul can be even as the body gets... less supple, to put it nicely. The problem, however, and the reason we regret and get embarrassed by our distractedness, is that we need our souls also to be mature; we don’t want to be distracted from our more serious, hopefully noble purposes by every triviality. Even if we wanted to be innocent little things forever, we can’t. Marco Lombardo goes on to lament that the world offers us so little formation, so inadequately curbs our bad curiosities and promotes our good delights, that our chances of mature success are slim. Dante knows how dangerous distraction can be: in the first canto of Inferno he finds himself at the edge of death, “in a dark wood,” but admits he cannot explain how he got there; “so full of sleep” was he “just at the point where [he] abandoned the true path” (Inf. 1.10–12).

So whatever distraction is exactly, we know it can be deadly, and whatever attention is, we know it deserves praise. St. Bernard of Clairvaux is praised in some early Cistercian texts because on one of his many peregrinations across Europe in defense of the unity of the Church, he walked past the entirety of Lake Geneva without noticing it; he had weighty matters in focus. This story recalls St. Benedict’s teaching on humility, a set of twelve steps toward attaining perfect love of God, the last of which says that the monk “manifests humility in his bearing no less than in his heart,” such that wherever he may be, whether walking, sitting, or standing, “his head must be bowed and his eyes cast down”; he keeps himself perfectly mindful of God’s judgment and constantly says to himself, with the tax collector of Luke 18:13, “Lord, I am a sinner, not worthy to look up to heaven” (Rule 7.62–66). In this, however, St. Benedict praises not an angry self-hatred but a radical attention and openness to receive. For St. Benedict is himself praised for having such an attitude and for receiving a marvelous vision. In the life of Benedict that Pope Gregory the Great (d. 604 CE) narrates, the elderly monk stood praying at his window in the depth of the night when a beam of light came in and he saw the whole world gathered into one within it, and the soul of a friend who had just died ascending from the world up into heaven in a fiery globe. As Gregory explains, the inner vision of the mind makes the soul “slacken” and expand: “It’s not that heaven and earth were contracted, but that the soul of the beholder was enlarged, rapt in God, so that it might see without difficulty that which is lower than God.”

Everything all at once: now that is a bold moment of attention—or the fulfillment of a long work of proper attention, all the more noteworthy considering how concrete and practical St. Benedict was in his life and in his Rule; his head did not float in the clouds. So how do we achieve this? How can we so train the little joy-child that is our soul that we are ready to really see what we need to see and not get dragged away by other things?

Isn’t it curious how the distraction develops in this story? First, lust—no surprise, though note it relates to food and confirms the importance of restraint in eating. Then the soldier temptation: Pachomius was a pagan soldier before he became a Christian monk and founder of large monastic “fortress-cities” in the Egyptian desert, so this is also a biographical temptation, a memory of the past. Then, straightforward noise and violence, the stress of life. But last of all (how clever!), the distraction of humor. The demons are reduced to child’s play, but somehow that innocent silliness proves the most dangerous—what harm is there to laugh a little? The story brilliantly boils down the nature of distraction and of victory over it.

We often blame technology for our distractedness, and Kreiner shows how this afflicted the ancient monks too. For them, though, the technology was the book, to which she dedicates her fourth chapter. St. Anthony the Great, the original Christian hermit, eschewed all use of books and simply lived from his memory of Scripture. But books could also be important tools for learning, obviously, for enabling the mind to make new connections. After all, as Kreiner observes, meditation was not about mere stillness, but about movement: “Minds that meditated were supposed to warm up, jump, stretch, hold tight. They made cognitive connections that felt like gathering flowers, concocting a medicine, or building something from salvage” (149). This ideal guided monks to illustrate their books in curious ways, adding all those figures and illuminations and complex designs that we might think of as distractions, but which were ways of calling attention to connections, guiding interpretation, and reminding the reader of the richness of meaning—think of those pages of the Lindisfarne Gospels, and what their beauty suggests about the riches of scripture. Of course, a good book could also become a good pillow, so discipline was necessary even in reading.

Besides well-made books, good stories too were essential. Much of the Christian monastic tradition is in the form of hagiography—stories about the holy women and men of the past and dialogues with them—because these striking stories are easy to remember and thus can help us fight distraction. Sometimes the memorable story is also slightly disturbing: Theodoret of Cyrrhus and the poet-theologian Jacob of Sarug (both in ancient Syria) report that the great St. Simeon, who is famous as a stylite (a monk who lives on an elevated pillar), stood for so long in prayer that one of his feet became “grossly infected” and, as the poetic homily explains, rather than stop for necessary help, Simeon just cuts off the bad foot and keeps praying on one foot. The story is not meant to teach a lesson about medical practice but to be a slightly freakish reminder of the importance of posture in prayer. You almost hear: “Remember how seriously Simeon took it! You can at least kneel a little or bow or sit up straight!” Kreiner explains that this tactic is part of the “visceral seeing” or “corporeal imagination” of late antiquity. One begins to wonder: is it not just technology that distracts us, but our lack of good stories? The new Simeon will not live on a pillar and cut off his foot; will it just be something about his phone?