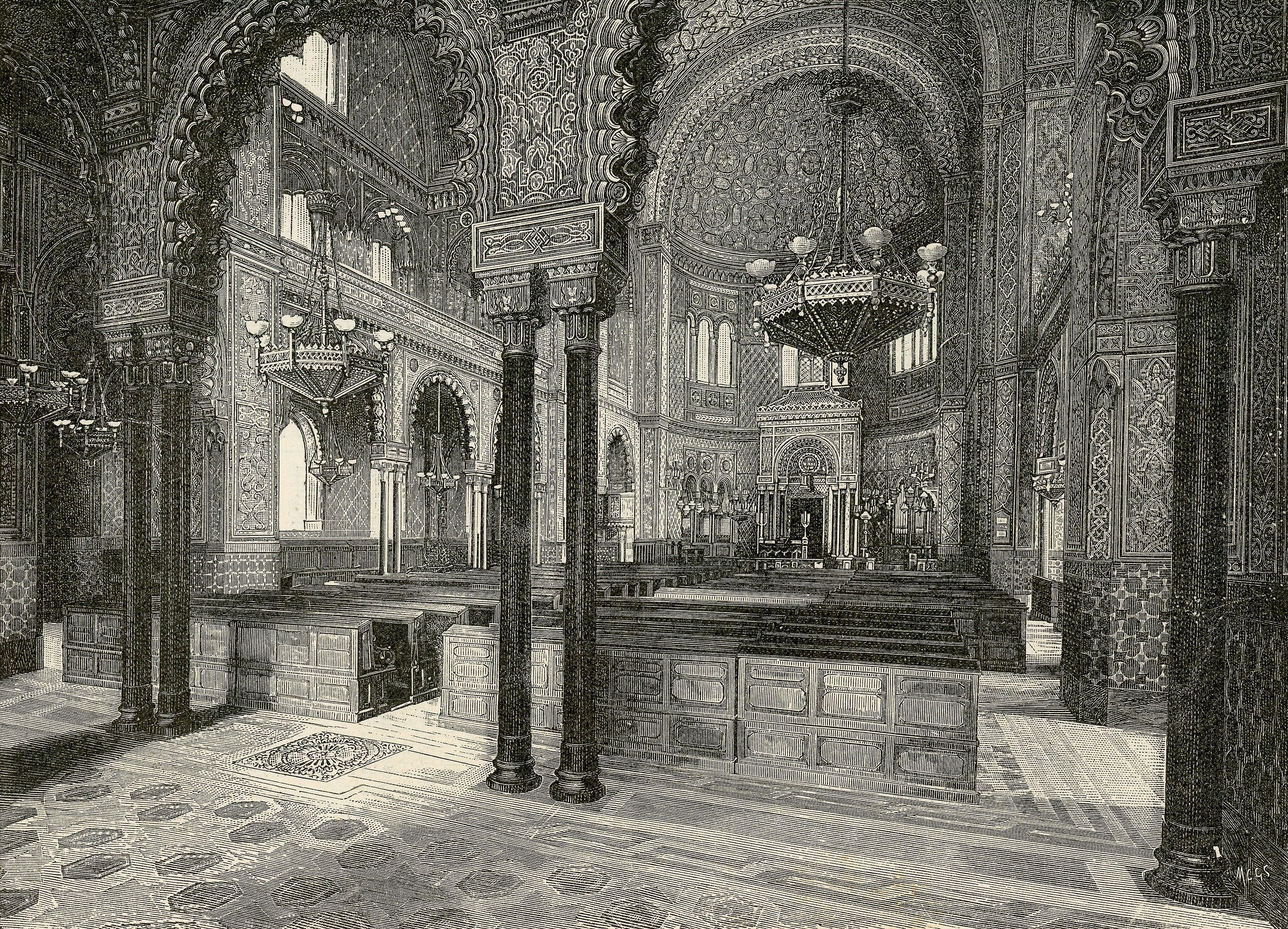

Interior of the Great Synagogue of Florence, Strafforello Gustavo, 1894

What religion is it that…

1. worships the one and only God, the God of Adam, Abraham, and Moses;

2. is scripture-based and law-centered;

3. begins its scripture with creation and ends it with redemption;

4. traces its origin to Abraham;

5. requires male circumcision;

6. calls for daily charity (Qur’an 2:226);

7. ordains multiple daily prayers (11:114);

8. affirms a resurrection and a judgment (3:16, 6:36, 22:69);

9. makes the case for resurrection as a rebirth (22:5);

10. considers Israel the People of the Book;

11. advocates pilgrimage to its religious center (22:26–37), to which it turns in prayer;

12. cites Moses saying to his people: “O my people, enter the holy land that I have ordained for you” (5:20);

13. prescribes frequent fasting (2:183);

14. proscribes the eating of pork, blood, or carrion (5:3, 16:115);

15. mandates ritual slaughtering;

16. commends the mention of God’s name before eating (6:121);

17. insists on the ceremonial washing of the hands (5:6);

18. requires head coverings and modest dress;

19. demands special consideration of orphans (4:10, 107:2);

20. prohibits usury of one’s own (3:130, 4:161);

21. designates a day of the week for prayer and scripture (62:9);

22. forbids marital relations during menses (2:22);

23. prohibits relations with one’s father’s wife (4:22); and

24. declares that taking one person’s life is tantamount to killing all mankind (5:32)?

Obviously, I am describing Islam (only the Qur’an is cited).

Obviously also, I am describing Judaism.1

With so much in common (the list above is illustrative only), how is it that Islam and Judaism are not working more closely together to bring about the universal acknowledgment of the one God and His program for humanity? On the contrary, the enmity between Muslims and Jews threatens to undermine for the nonbeliever the credibility of the one and only God, blessed is He. If those who call Abraham “father” cannot get along, what are people to think of their God, who is proclaimed “king and father of us all”?

We are living in times of unprecedented religious opportunity. God has given the Abrahamic family a window of opportunity to advance beyond sibling rivalry in the direction of fraternal cooperation. We are moving from being islands in the worship of the one God to peninsulas reaching out to one another. The either/or mentality of the past is giving way to the both/and of the present. Our link to Abraham, through posterity or through membership in his household, facilitates our working together to bring others to the recognition and worship of the one God. This is achieved by following Abraham “in keeping the way of the Lord by doing what is right and just” (Genesis 18:18). Anyone who worships the one God becomes a witness to God (shāhid). We either testify truthfully by our deeds or we bear false witness by our deeds.

Judaism dubs a moral action in the name of God as “the sanctification of God’s name” (kiddush Hashem) and its opposite as “the desecration of God’s name” (ĥillul Hashem). Whenever we bear witness to God’s commitment to righteousness and justice, we sanctify God’s name; whenever we testify falsely, we desecrate God’s name. As the worshipers of the one God, we hold the keys to God’s reputation. The honor of God’s name, may it be blessed, is contingent on us and our deeds.

When the worshippers of the one God promote life, peace, and justice equally, they become the sanctifiers of God’s name; when the worshippers of the one God promote death, conflict, and injustice, they become desecrators of God’s name. In reality, it is impossible for one to affirm that “he who kills a single life is as though he killed all mankind” (Qur’an 5:32) and then to kill in the name of God. To do so makes God small, not great. There is no greater sacrilege than killing the pride of God’s creation in the name of the living God. According to the Oral Torah, “Anyone who sheds the blood of man diminishes the presence of God.” Murder is literally blasphemy, guaranteeing a place in hell.

To merit the title “the children of Abraham” requires a commitment to an “alliance of Abraham”—that is, a commitment to carrying on Abraham’s legacy. As the Qur’an says (8:68), the nearest of all people to Abraham are those who follow him. Then why is intolerance among the peoples of Abraham so rampant that it threatens to undermine the formation of any partnership for bringing about the universal recognition of the one God, blessed be He?

One answer is that attitudes to tolerance correlate with approaches to truth. What impedes an Abrahamic alliance is the illusion of having a monopoly on the truth. If one party has all the truth, the other has nothing. Lacking truth leads to lacking validity; lacking validity leads to lacking the right to be. Nothing is more threatening to the alliance than one party claiming a monopoly on the truth. As followers in the footsteps of Abraham, we should see ourselves as seekers of the truth, like Abraham (Qur’an 6:74–83),2 not as owners of it. Religious people are possessed by the truth, not possessors of it.

There is an illuminating Jewish tradition on this score. It goes back to the creation of humanity. Like Qur’an 2:38, it reports the angelic opposition to the creation of man, telling us that

When the Holy One, blessed be He,

came to create man,

the ministering angels were divided

into camps and factions.

Some said, “Let man be created”;

others said, “Let man not be created.”

The angels are identified with the four religious qualities: truth, kindness, justice, and peace, based on Psalm 85:11:

Kindness said: “Let man be created,

for he will perform acts of kindness.”

Truth said: “Let man not be created,

for he reeks of deceit.”

Justice said: “Let man be created, for

he will perform acts of justice.”

Peace said: “Let man not be created,

for he is full of contentiousness.”

With a split vote of two and two, what was the All-Merciful to do? We all can notice that man has been created. People thus assume that the All-Merciful simply outvoted Truth, siding with Kindness and Justice against Truth and Peace, making it a vote of three to two, thus bringing about the creation of man through democratic means.

No, says the tradition. Rather, the Holy One, blessed be He, grabbed Truth and threw it out of the court. Why expel Truth from the heavenly deliberations when God could have tilted the scales by joining with Kindness and Justice? The answer is that Truth is God’s signature and that even God can’t overrule His own seal of truth.

The Central Synagogue of Aleppo; photo: Wikimedia Commons, Govorkov

Truth is identified as God’s seal, not man’s. God alone exercises a monopoly on the truth, not human beings. We are seekers of the truth; God is owner of the truth. We at the most grasp part of the truth; God grasps the whole truth. Thus, we pray, “Guide me in Your truth and teach me” (Psalm 25:5). Nothing verges on the idolatrous more than laying claim to divine prerogatives. When man arrogates to himself divine prerogatives, he closes himself off to the divine. This obtains even were one to claim only that one’s revelation exhausted the truth. Everybody knows that every scripture has generated multiple schools of interpretation, precluding any school of interpretation from having a monopoly even on the meaning of its own scripture. And even if there were such a monopoly, it would not prevent fallibility. As we all know, fallibility and humanity go together. Only God qualifies for infallibility.

No human being can claim a monopoly on God’s meaning in scripture. In fact, as time goes on, we understand more and more of scripture, implying a growth in truth. Like a good fragrance, scriptures do not release all their truth at any one time, to any one generation, even less to any one individual. Rather than laying claim to the whole truth, the religious person seeks to grow in truth. We are servants of the truth; God is the master of the truth.

Were I summoned to court, sworn to tell the truth—the whole truth, and nothing but the truth—I would say, “I can tell the truth, and nothing but the truth, but I cannot tell the whole truth: that is a divine prerogative.” We are not authorized to usurp divine exclusivities. All human perspectives are partial. Only God has the whole picture. We cannot even see the front and back of a book simultaneously. We are like the proverbial blind men grabbing parts of the elephant, trying to figure out what it is.

Religious tolerance is predicated on the recognition that we are not to “play God,” blessed be He. We call God “all-knowing,” for God and God alone knows and understands all. As the Jewish theologian Joseph Albo said about God, “If I knew Him, I would be Him.”

The alternative is a principled pluralism, not relativism. It opposes relativism as it opposes absolutism. It affirms the human capacity for making truth claims. One can even legitimately claim the greater truth of one’s religion. Having more truth, however, is not tantamount to having all the truth. That only God, blessed be He, has. As religious people, we trust only God to have the whole truth, as the Qur’an says (3:159): “God loves those who trust in Him.”

Awareness of the pluralism of truth safeguards against exaggerated claims and religious smugness. It allows for the existence of competing visions of the truth where there is a commonality of goals and a commitment to grow in truth.

An example of this is the controversies between the ancient exegetical schools of Hillel and Shammai. According to the tradition, the schools of Hillel and Shammai are examples par excellence of controversies “for the sake of heaven.” For years, each school argued its case, claiming it was right, implying the other was wrong. Finally, a heavenly voice proclaimed about the views of both schools: “These and those are the words of the living God, but practice follows the school of Hillel.”

Now how can opposing views both be the words of the living God? The answer of the tradition is that both parties sought truth, not victory. Indeed, when parties struggle for the truth, their controversies are dubbed “for the sake of heaven,” destined to endure. Why is this so? Should not the quest for truth lead to harmony, or at least resolution? No, says the tradition, the pursuit of truth is an ongoing process, leading to a clash of opinions. The more intense the quest, the less the unanimity. Such controversies endure beyond their original advocates. This is not the case with self-serving controversies, in which disputes are resolvable by the death of one of the parties. Since the issue was personal, gain or loss decides the conflict.

These competing exegetical schools argued over the full range of Jewish legal issues and worldviews. The more than three hundred recorded controversies between them deal with issues of personal life, blessings and prayers, the separation of priestly dues and tithes, marriage and divorce, Levitical purity and abstinence, sacrifices and the priestly service, as well as civil and capital cases, not to mention the order of creation and the worthwhileness of life.

God has given the Abrahamic family a window of opportunity to advance beyond sibling rivalry in the direction of fraternal cooperation.

How did the controversies affect the relationship between the two schools? There are two pictures of their relationship: one of violent conflict, the other of respectful disagreement. According to the first, the school of Shammai once outvoted that of Hillel, issuing eighteen prohibitions over the objections of the school of Hillel. How did the school of Shammai succeed against the more numerous school of Hillel? The answer is that the school of Shammai ambushed the school of Hillel, slaying most of them. The six who escaped to make their way to the academy were insufficient to stave off the negative vote. Thus, the school of Shammai carried the day. A similar violent picture is recorded elsewhere. Both sources conclude that the day the school of Shammai achieved victory was as calamitous as the day the golden calf was made—a potent picture of how sincerity of motive (“for the sake of heaven”) and the resort to violence coalesce. The claim to the possession of all the truth paves the way to the delegitimization of the other and the arrogation to oneself of the right, if not the duty, to eliminate others as opponents of the truth.

According to Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin, in the introduction to his commentary on Genesis, the reason for the violence was:

The people then were religious, and pious… but they were not honest in their general conduct. Because of the baseless hatred lodged in their heart, whomever they saw deviating from their opinion of religion was suspected of heresy. Accordingly, they came to bloodshed and all other evils of the world.... Since God, blessed be He, is honest, however, He does not tolerate such religious people unless they walk honestly and not crookedly, even if their motive is for the sake of heaven.

Religious motives alone are insufficient safeguards for preventing conflicts from erupting into violence. On the contrary, the belief that one is acting for the sake of heaven and “for the greater glory of God” may goad one to commit violence against an opponent, who is perceived as acting only out of self-interest. Such was the way of the Shammaites.

Were the Hillelites any different? The same work of the Oral Torah describes Hillel’s way as that of “loving peace, pursuing peace, loving humanity, and bringing them nigh to the Torah.” It is no wonder that the Talmud describes Hillel’s patience with abrasive potential converts as “bringing them nigh to the Torah.”

Is it possible to maintain that alternative policies are bridgeable by respect and tolerance? There is no mention that both parties considered the other’s words to be of the living God. That was left to the determination of the heavenly voice. But how can the heavenly voice claim that conflicting positions reflect God’s word? One answer proposed is that different positions are true for different ages; another is that different positions are valid for different contingencies. Yet another alternative is the realization that both perspectives are inspired and address the same problem, with neither being spun out of ulterior motives. The validity of both confirms the existence of alternative ways of grasping the divine word. Since the fullness of the divine word cannot be contained in a single human perspective, a plurality of perspectives and understandings is needed to fill out the human grasp of divine truth. Even revelation, says Judaism, was appropriated according to the capacity of the recipient. Once divine expressions, however, are reduced to human linguistic formulations, they become subject to all the ambiguities and limitations of language.

The recognition of plural solutions need not lead to paralysis. For one thing, as mentioned, different solutions may apply to different times or circumstances; for another, they may reflect that the totality of a problem requires more than one solution, or indeed, even what appear at times to be conflicting solutions.

The whole truth is an object of divine cognition alone; it exceeds human grasp. Since any human perspective is limited to part of the truth, the whole truth may not be graspable without contradiction. This may be what the physicist Niels Bohr meant when he said, “The opposite of a correct statement is a false statement. But the opposite of a profound truth may be another profound truth.” An understanding of the limited nature of human truth, as opposed to divine truth, is poignantly expressed by Rabbi Aryeh Leib Heller in his introduction to the fourth part of the Jewish Code of Law, entitled K’tsot ha-Ĥoshen:

One trembles at the thought that one might say about the Torah things that are not true, i.e., that the human mind is too weak to grasp the truth…. The Torah was not given to ministering angels. It was given to man with a human mind. He gave us the Torah in conformity with the ability of the human mind to decide, even though it may not be the Truth... [but only] be true according to the conclusions of the human mind.

Since the truth is the seal of the Holy One, blessed be He, we must concur with a description by Solomon Schechter of the Gaon of Vilna: “Neither men nor angels are trusted with the great Seal. They are only allowed to catch a glimpse of it, or rather to long after this glimpse. However, even the longing and effort for this glimpse will bring man into communion with God and make his life divine.”

It is the commitment to the fullness of truth that enables one to navigate between the perils of relativism and those of absolutism. For the first, anything goes; for the other, everything but itself is condemned. Our commitment to a pluralism of viewpoints sprouts not from the soil of indifference nor from the erosion of religious conviction but from the heterogeneity of human knowledge and richness of method.

What is that method? According to the Oral Torah, the school of Hillel did not prevail because of the heavenly voice, but rather the voice sided with them because “They were receptive and self-effacing.” They were receptive in that they studied their rulings along with those of the school of Shammai; they were self-effacing in that they taught the other position before advancing their own.

The Hillelite policy conformed to that confirmed by the divine voice—namely, the assumption that conflicting views can be equally committed to the truth. They, however, did not mistake their passion for truth with its possession. Instead, they felt duty bound to ensure that their disciples hear the alternative view by teaching it to them first. That did not entail any lessening of commitment to their understanding of the truth as they perceived it, only that they sundered the nexus between right and legitimacy. While only one may be right, both are legitimate as long as both strive for the truth for the sake of heaven.

This also explains the defeat of the school of Shammai. Not only did they not teach the other position first, but they refused it a hearing at all. After all, since they were toiling for the sake of heaven and possessed the truth, were they not entitled, indeed obliged, to protect God’s truth? For them, error had no rights and was unworthy of being taught to impressionable students. It is not coincidental that the same school that refused to give the school of Hillel a hearing was the very school that resorted to violence to secure ideological victory.

I can tell the truth, and nothing but the truth, but I cannot tell the whole truth: that is a divine prerogative.

Once delegitimization sets in, it knows no bounds. By initially laying claim to no less than 51 percent of the truth, commitment can be maintained without feeling obliged to negate alternatives. Total commitment to a vision of truth need not necessitate the belief that the truth is exhausted by that vision. On the contrary, as the above method attests, by attending to the truth in other views, one’s own truth tends to grow.

By teaching the alternative position in their academy, the school of Hillel had to wrestle with the alternative. In order to retain the loyalty of their students, the Hillelites had to upgrade their arguments. By sifting out the chaff from the wheat, their final stances were all the stronger. The result was transformative. The school of Hillel carried the day. Indeed, the tradition reports multiple cases of the school of Hillel reversing its position in favor of Shammai, but at the most only one instance in which the school of Shammai acted accordingly. For Shammai, truth was a closed system that speaks with a brittle univocity. But truth unchallenged, not revitalized by argument, tends to lose its cogency. Unable to bend, it breaks. In the end, they lost. The Shammaite position illustrates that in the presence of monopolistic claims on the truth, truth stagnates, differences lead to mistrust, diversity threatens unity, and violence gets legitimated.

The Shammaites lacked sympathy for complexity, and tolerance for ambiguity. When the quest for unambiguous solutions of complex problems is driven by simple-mindedness, it can lead to violence against the other to eliminate the alternative and to quell one’s own doubts. The drive for premature certitude leads to impugning the other’s motives, believing that were they really interested in the truth, they would concur with us. The more we make of our opponents one-dimensional cardboard figures, the easier it is to disdain them or even to eliminate them.

The Hillelite position, on the other hand, demonstrates that a pluralistic mentality can sustain collegiality in the face of diversity. It is not easy to hold that pluralistic understandings of the Torah are consonant with its divine origin. Yet the divine origin of the Torah does not guarantee singleness of meaning. A student of the Torah must develop receptivity to the various manifestations of truth. This demands a high tolerance for ambiguity. When people, however, are educated to believe that their truth claims are exhaustive, their tolerance for ambiguity diminishes. But without such tolerance, God’s revelation in all its dialectical fullness will overwhelm the prospective student, leaving him or her with a smaller truth rather than a greater one.

Differences become tolerable when room for them is allocated in the divine economy. Coordinated action is possible to the degree that there are common aims. The previous Chief Rabbi of Palestine (now Israel), Abraham Kook, explains in his commentary to the Prayer Book why pious scholars are called builders:

For the building is constructed from various parts, and the truth of the light of the world will be built from various dimensions, from various approaches, for these and those are the words of the living God.... It is precisely the multiplicity of opinions which derive from variegated souls and backgrounds which enriches wisdom and brings about its enlargement. In the end, all matters will be properly understood and it will be recognized that it was impossible for the structure of peace to be built without those trends which appeared to be in conflict.

Diversity of perspective is also a function of diversity of role. Again, differences become tolerable, indeed desirable, to the degree that we serve some common goals. In our case, it is to bring about the magnification and sanctification of the divine name, blessed be He.

How is this relevant for forming an alliance of virtue among the three Abrahamic religions? Assuming the God of history has an outline for history, we need to ask how the competing claims to the legacy of Abraham can be coordinated to further a divine vision. One model for this, envisioned by the great Moses Maimonides almost a millennium ago, concludes his code of Jewish law:

It is beyond the human mind to fathom the designs of the Creator; for our ways are not His ways, neither are our thoughts His thoughts. All these matters relating to Jesus of Nazareth and Mohammed, who came after him, only served to… prepare the whole world to worship God with one accord, as it is written, “For then will I turn to the peoples in an intelligible language, that they may all call upon the name of the Lord to serve Him with one accord” (Zephaniah 3:9). Thus, the messianic hope, the Torah, and the commandments have become familiar topics of conversation in the far isles and among the many peoples.

Our task is to envision a contemporary model for the constituents of the Abrahamic family to effectuate the magnification and sanctification of the divine name for the redemption of all.

As a Jewish contribution to the project, here is the agenda of the Aleinu prayer that concludes every service, thrice daily:

Therefore, we put our hope in You,

Adonai, our God:

To see soon the radiance of Your might;

To remove all idols from the earth so

that all false gods will be totally eliminated;

To establish the world as the kingdom

of God so that all the people of flesh

will call upon Your name; To turn to You all the wicked of the

earth: all the inhabitants of the world

will recognize and know

That to You every knee will bend and

every tongue vow.

Before You, Adonai our God, they will

bend and kneel, thereby rendering

glory to the honor of Your name.

Namely, they all will accept the

authority of Your kingship so that

You will quickly reign over them forever,

For kingship is Yours, and for ever and

ever may You reign in honor.

As it is written in Your Torah: “Adonai

will reign for ever and ever” (Exodus 15:18).

And it is said: “And Adonai will be king

over the whole earth; on that day,

God will be One and His name One”

(Zechariah 14:9).

The religious challenge of this generation is to orchestrate the commonalities and diversities of the Abrahamic religions into a symphony. The symphony of religious life results from each playing its own instrument well, aware that the richness of the music produced together exceeds that produced separately. Harmony results from differences coordinated, not suppressed. Although focused on making our own music, we minimize cacophony by maximizing harmony, advancing the goal of the orchestra to produce a symphony.

In other terms, just as biodiversity can create a richer agricultural yield, so can religious diversity generate a richer theological vision of God’s truth for humanity.

A version of this essay was delivered as a talk at the sixth assembly of the Forum for Promoting Peace in Muslim Societies, Abu Dhabi, December 10, 2019.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy