Color Study, Squares with Concentric Circles, Vassily Kandinsky, 1913

Equality words become operative only when a preposition and its object are adjoined to them. “He is equal” is in-significant speech.

So we must say: “equal to,” “the equal of,” “on an equal footing with”; adjective, noun, abstract noun; “equal to my neighbor,” “anybody’s equal.”

Thus no one and nothing can be merely equal. Mere was once used by the great Queen Elizabeth in this locution: “I am,” she said, “mere English.” She meant “nothing but, altogether,” for her birth and her allegiances were being questioned. It is possible to be mere English, less likely when you’re American, and impossible if you’re an immigrant.

It is, however, possible for anyone to be merely kind, that is, kind without ulterior motive—without alloy. Equal, though, you can’t be merely; you have to choose a partner-in-comparison: “I demand equality with…” requires a choice, usually of a category. “I’m every bit his equal” will usually involve a person; “I’m equal to anything,” a qualified situation.

Terms, and the being they denote, that do not need the prepositions, or have them in an odd way, I’ll call, for present purposes, “self-terminal”; they are the two terminals of a relation without a distance—a self-relation. Good is such a term, among the Platonists the chief such term. People are “good at” a job or “good for” each other. But they, and beings higher and lower than they, are also good-in-themselves, just good, merely good—good for nothing in particular but for everything in general. There certainly are such people, also such tools, foods, books—they are what you might call the world’s handymen/women. (I write the last word merely from a friendly desire to show attention to my world’s current silliness.)

Such self-terminals are usually acknowledged by speaking of “good-in-itself,” or The Good (which, in the one Platonic dialogue in which it is mentioned, Republic VI, is described as not only good-in-itself—that is, self-sufficiently, non-relatively good—but also good for bringing a world into being, nourishing it, and making it intelligible). In other words, The Good is, at once, a divinity to be sought for itself, the source of the world’s existence and flourishing, and, above all, of its being understandable by us.

To the well-made and well-governed pagan cosmos, the Christians contribute the notion of human beings as invaluable, as being beyond price, priceless, and thus to be priced way beyond this or that valuable property. Therefore they are incomparable.

I think that many, if not most, Americans willing to declare themselves on this matter—though they might balk at the high-toned locution—would agree to the proposition that all human beings are, in some deep way, priceless, along with being incomparable, and that, in consequence, their lives are untouchable. That is expressed in the majority opposition to the death penalty: even a person who is guilty of the two ultimate crimes of violating a child and committing murder (that is, a killing not done within the law) is to be let to live.

So arises a very confounding perplexity: Why would an incomparable being, the only such kind in our natural world (for all other species provide specimens for study, and specimens would not be representative of their species were they not eminently comparable)—why would, or should, such a being, a human being, be devoted to, even zealous for, equality?

I won’t attempt here to document the pervasiveness of references to equality as a good whose universal approval can be taken for granted. Such proof would overwhelm all other text. I have ringing in my ear a half-caught phrase I read in an international magazine I subscribe to, something to the effect that government-sponsored medical insurance would provide the equal universal coverage we all wish for. Let it stand for the barrage of examples.

Before I launch into my inquiry about equality, a word about equity, a recent bi-word intended to supersede equality. It is a ratcheting up that was to be expected. Equity is, to my mind, a sort of superequality, compensatory inequality. It is a world apart from the natural inequality that appeals to me.

Here is the stark fact about equality, suppressed, perversely, by its very obviousness, but ultimately all-significant: equality is a relation. And it is a mere relation. If you’re equal to someone—to anyone who might be a candidate for being above or below you in some respect—in wealth or reputation or personal happiness—you are nothing that is substantial, except “equal to.” Equality, for better or worse, bestows nothing. A more explicit treatment requires a somewhat abstract inquiry that involves terms somewhat devoid of the living color of human experience, drawn off (Latin: ab-trahere) from our feelings, food, passions, projects—but then, nothing is more concrete, more dense in significance, than an idea.

These different etymologies seem to me to betoken very different takes on equality, perhaps even indicative of national character—though that is to me dubious territory. I am relying here on the usual translation of equality and Gleichheit into each other, as in “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité,” which goes into “Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit.” German equality is not a leveling, being on a plane or topping out at the same height: the metaphorical eradication of spatial difference. It is rather similarity, a sort of defective identity of looks—a likeness, that of belonging to the same kind. Whatever items, however, belong to the same kind only have a kind of sameness. For they are, if the same in kind, different in not being the same item. In fact, they are twice different: once for being two rather than one, and twice for being similar rather than identical. I’ve just referred to sameness as defective identity. I mean that sameness differs from identity. The latter is, as a relation, either self-sameness, a relation a self can have to itself, though perforce a distance-less relation, or self-diremption, again a relation of self to self, but now, of necessity, a self-distancing. It’s the same relation but seen—one in being but two in thinking—from a different perspective, one might even say, of mood. So by calling same-ness “defective identity,” I mean that—by Leibniz’s dictum, which declares that indiscernibles are identical, since to be the same there need to be at least two—these two must be discernibly different, so imperfectly identical.

In sum, so far, equal can be “level in quantity” or “same in shape.” I might say here in passing that the former is unproblematic: line the two amounts up in sequence and if they end together, they’re equal. Or put them in that notional balance, the equation. But the latter is deeply problematic. Let me first say that by “same in shape” I don’t mean “similar.” Similar means, etymologically, “same-like,” so not altogether same—the biggest distinction being that in our world, by a mysterious special blessing, shapes can be the same shape-wise but different size-wise. In geometry, shapes of this latter type are called “similar”; when they share size as well as shape, we call them “congruent.”

A little difficulty arises. There is no way to prove congruence except by coincidence upon superimposition, be it part by part of a figure or whole upon whole. Such coincidence is, however, futile, because neither physical bodies nor geometric figures can really, illuminatingly, coincide. First, bodies can’t coincide because they’re bodies and two bodies can’t be in the same place, and geometric figures can’t be carried safely, without deformation, from one place to another. Second, if you could make bodies or figures coincide, they would immediately disappear into one another, while congruence, equality in size, has to have two terms, since equality is a relation. So congruence is pretty opaque, and Gleichheit, shape-equality, is not so clear.

I should mention here that in German, in fact, both the Latin and Germanic terms are available. I can say: “Das ist mir ganz egal,” “That’s all the same to me” (with a note of cosmopolitan snideness). Or I can say: “Das ist mir gleich,” “I don’t care one way or the other” (in a tone of distanced indifference or masked disillusionment). So much, very minimally recorded, for experiences in speech. No reader will lack them.

Now to the question of central concern: equality is, inspected as a locution, a relation. What kind of a relation? I’ve already said a comparison, though strictly speaking, it might not make sense to talk of being more or less equal; if the items in a pair are not strictly equal, they’re unequal. Yet, because the fall-off from equality is often in a fairly orderly sequence, it does seem permissible to speak of the closest neighbors to the leading examples as being progressively more equal to it; for example, the higher you rise on a salary scale, the more equal you are to the top salary. (A pertinent reminiscence: We were hosting a transatlantic philosophy professor who informed us suitably ill-paid teachers of the liberal arts: “Ich, naturlich, beziehe Spitzengehalt,” “I, naturally, draw a peak salary.” He made our day.) A more genuine description of equality is that equal is unique while unequal is multifarious. For wherever comparison is possible, when items in a pool of comparables are pronounced equal, you know just what must be the case for them to be so called: some measure, count, or description makes them so. When, however, they’re pronounced unequal, you know that their actual relation might be anything amongst their possible pertinent properties. Because there is an indefinite quantity of possible properties on either side of equal, unequal covers a multitude of sins, and equal offers unique rectitude. Of course, that rectitude might be boring.

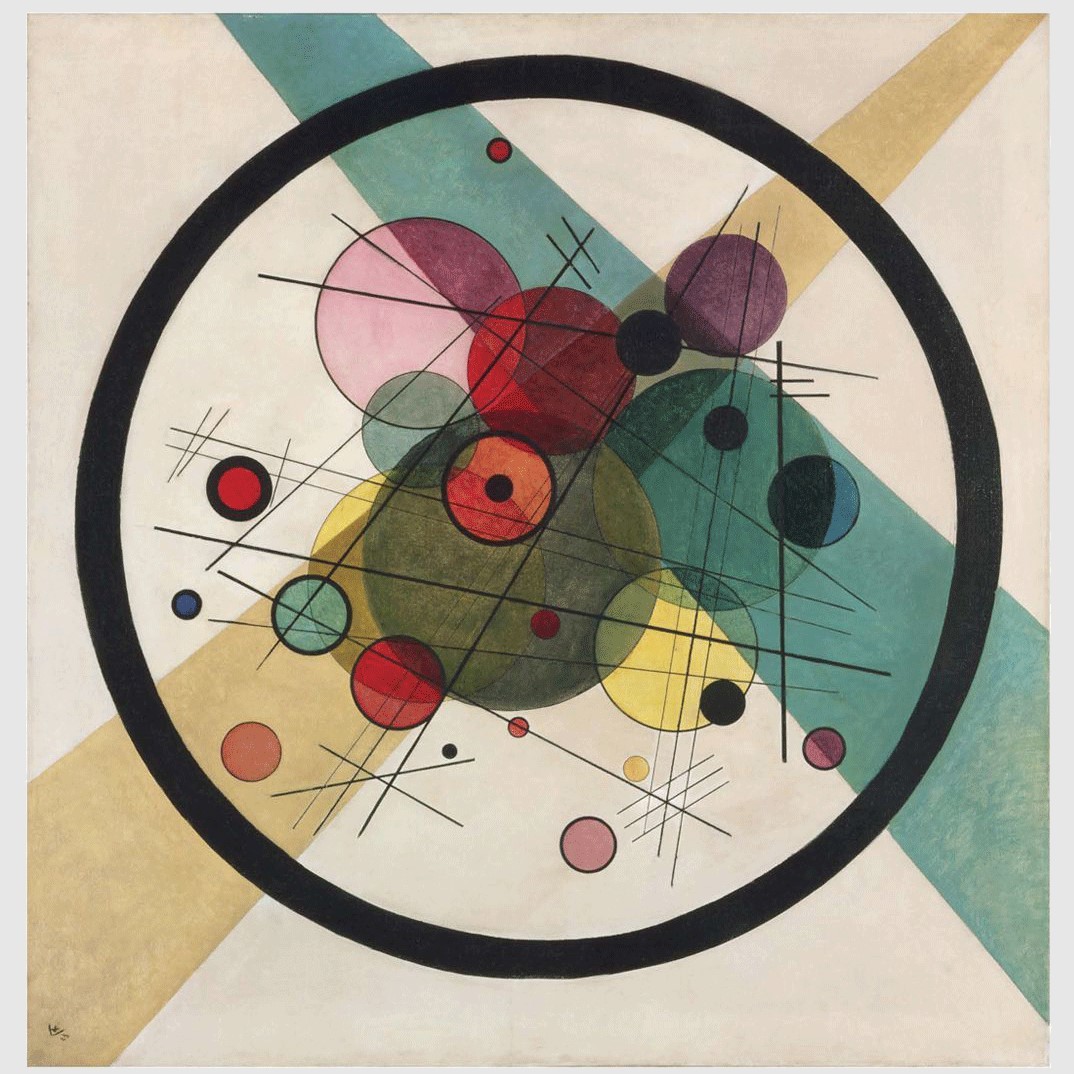

Circles in a Circle, Vassily Kandinsky, 1923

But no, as a sort of hinge between more or less, many and few, excessive and scanty in the realm of assessment, and as a sort of falling-short in the territory of identity, equality is full of those perplexities that adhere to really interesting notions. Such notions ask to be penetrated to their essence. But equality is a relation, and relations, congenitally betwixt and between, evade essence, the verbal articulation of a substantial being, one that is concretely there, real, “thingly.” So, without retracting its relationality, even relying on it, I want to say that equality is shown to have its vitality by the fact that it has its own, very particular, vices: envy and resentment. Anything so strong featured must have some potency. I think this holds for the equality-relation, very especially.

Since equality is, so to speak, essentially a relation, it depends, once more, on comparison, and comparison evokes close inspection—especially so since equality is a relation of near sameness, all-but identity, as-close-as-possible similarity. So narrow, peering scrutiny is the mode of equality-regard: Are they beneficiaries of something I’m entitled to? Do they have privileges I deserve? Have they just plain got more than me?

Yet because of the complexity of private, social, and professional life, all carried on simultaneously, and a practically inexhaustible complexity of goods and ills, in both kind (modality) and quantity (degree), perfect equality is never attainable, and if there is hunger for it, it is never assuaged. The passions, the vices, that energize this unsociable socializing, this respectless regard, are, as I’ve said, envy and resentment.