Jun 13, 2018

From Savagery to Civilization

University of Dallas

Scott F. Crider has published extensively on the works of William Shakespeare and maintains the English Renaissance as one of his major research interests.

More About this Author

University of Dallas

Scott F. Crider has published extensively on the works of William Shakespeare and maintains the English Renaissance as one of his major research interests.

More About this Author

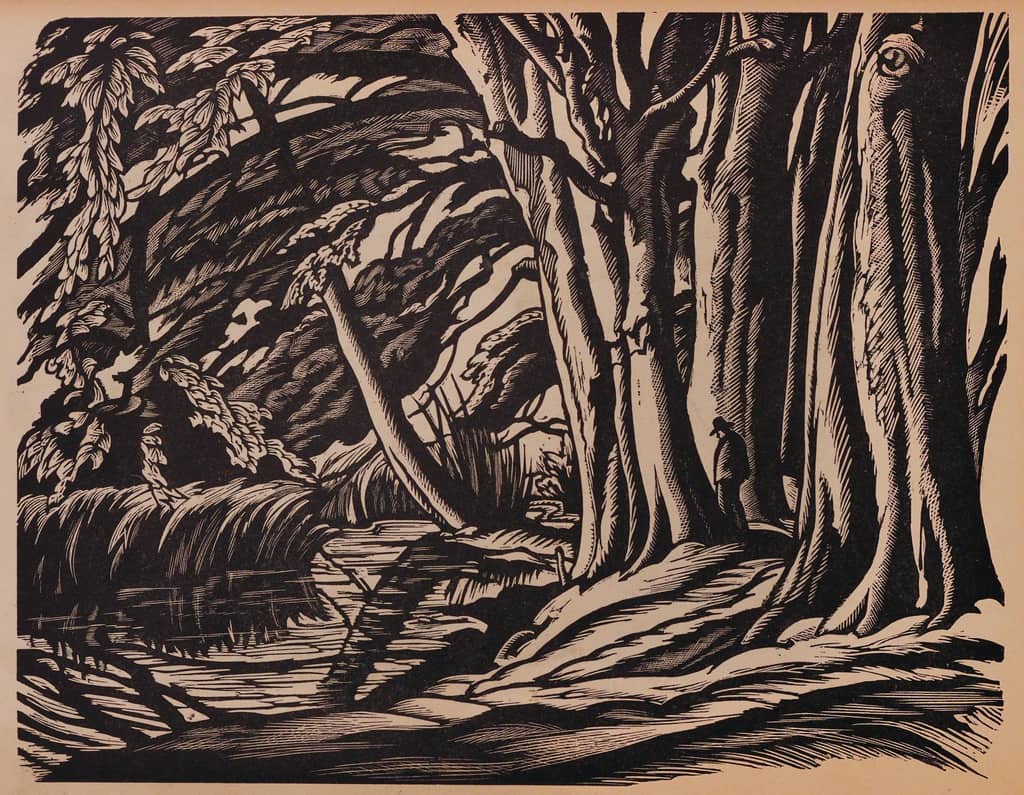

"The New Woodcut," Malcolm Salaman, c. 1930

There is an understudied genre of literature in the West one might name “Myths of the Origin of Language.” The most famous instance of the genre is Cicero’s—first in de Inventione (On Invention), then in de Oratore (On the Orator). The myth is simple: once upon a time, human beings weren’t human yet since they lacked language; a great founder then gave them language, and they became truly human. Cicero likes the myth so much that he tells it twice. Here it is from de Inventione:

For there was a time when men wandered at large in the fields like animals and lived on wild fare; they did nothing by the guidance of reason, but relied chiefly on physical strength; there was as yet no ordered system of religious worship nor of social duties; no one had seen legitimate marriage nor had anyone looked upon children whom he knew to be his own; nor had they learned the advantages of an equitable code of law. And so through their ignorance and error blind and unreasoning passion satisfied itself by misuse of bodily strength, which is a very dangerous servant.

At this juncture a man—great and wise I am sure—became aware of the power latent in man and the wide field offered by his mind for great achievements if one could develop this power and improve it by instruction. Men were scattered in the fields and hidden in sylvan retreats when he assembled and gathered them in accordance with a plan; he introduced them to every useful and honorable occupation, though they cried out against it at first because of its novelty; and then when through reason and eloquence they had listened with greater attention, he transformed them from wild savages into a kind and gentle folk. (1.1.2)1

As with so many other early modern English writers educated in the Latinate rhetorical tradition, George Puttenham knew this myth well.2 He retells Cicero’s myth in the opening chapters of The Arte of English Poesie, a popular work in late-sixteenth-century England. The book as a whole is no doubt of little interest to non-specialists, but the myth itself should be extremely interesting to anyone interested in poetry and the human. In Puttenham’s retelling of the Ciceronian myth, the inventor of language and human civilization is no longer an orator but a poet—or, rather, a crew of poets. Why? The first reason is historical: rhetoric (the art of persuasion) and poetry (the art of representation) were not considered wholly separate arts until the early modern period.3 But I want to focus on the second reason. While both rhetoric and poetry are productive arts, poetry—perhaps because of its name, poiein, meaning “to make” in Greek—emphasizes the constructive, fabricating power of language. If what makes us human is language—and it is, whether one believes language is natural, cultural, or a combination of the two4—then what fulfills our humanity most is the language that makes human culture, a culture which, in turn, remakes us from savagery to civilization. Poetry is an architectonic art for Puttenham because the most important arts—the art of politics, for example—all rely on the power of language to remake humanity in the culture that is humanity’s habiliment, and its principles of ordering its representation—through meter, stanza, and figuration—are in deep accord with the soul’s longing for ethical, political, and cosmic ordering.

“Before the world-historical event of language, we were rather unimpressive—living in the wild, 'vagrant and dispersed like the wild beasts, lawless and naked.'”

Hamza Yusuf joined Scott Crider to discuss the function and finer details of poetry in our time.

The work opens with his definition: “A poet is as much to say a maker” (93).5 And, for Puttenham, that is why poets are like the God of the Hebrew Bible: they may be described as “creating gods” (94). Even so, they are also imitators since they represent what has already been made by God: “[P]oesy [is] an art not only of making, but also of imitation.” The poet is both human—derivative of God in mimesis, or representation—and divine—original like God in poiesis, or making: the poet imitates what is already made, and the poet makes what has never been made before. Interestingly, after what looks like a digression of English prosody, Puttenham tells his myth proper. I include it in full:

The profession and use of poesy is most ancient from the beginning, and not, as many erroneously suppose, after, but before any civil society was among men. For it is written that poesy was the original cause and occasion of their first assemblies, when, before, the people remained in the woods and mountains, vagrant and dispersed like the wild beasts, lawless and naked, or very ill clad, and of all good and necessary provision for harbor or sustenance utterly unfurnished, so as they little differed for their manner of life from the very brute beasts of the field. Whereupon it is feigned that Amphion and Orpheus, two poets of the first ages, one of them, to wit Amphion, built up cities and reared walls with the stones that came in heaps to the sound of his harp, figuring thereby the mollifying of hard and stony hearts by his sweet and eloquent persuasion. And Orpheus assembled the wild beasts to come in herds to hearken to his music and by that means made them tame, implying thereby how by his discrete and wholesome lessons uttered in harmony and with melodious instruments, he brought the rude and savage people to a more civil and orderly life, nothing, as it seemeth, more prevailing or fit to redress and edify the cruel and sturdy courage of man than it. And as these two poets, and Linus before them, and Musaeus also and Hesiod, in Greece and Arcadia, so by all likelihood had more poets done in other places and in other ages before them, though there be no remembrance left of them by reason of the records by some accident of time perished and failing. Poets therefore are of great antiquity.

Then forasmuch as they were the first that intended to the observation of nature and her works, and especially of the celestial courses, by reason of the continual motion of the heavens, searching after the first mover and from thence by degrees coming to know and consider of the substances separate and abstract, which we call the divine intelligences or good angels (daemones), they were the first that instituted sacrifices of placation, with invocations and worship to them as to gods, and invented and established all the rest of the observances and ceremonies of religion, and so were the first priests and ministers of the holy mysteries. And because, for the better execution of that high charge and function, it behooved them to live chaste and in all holiness of life and in continual study and contemplation, they came by instinct divine and by deep meditation and much abstinence (the same assubtiling and refining their spirits) to be made apt to receive visions both waking and sleeping, which made them utter prophesies and foretell things to come. So also were they the first prophets or seers (videntes), for so the scripture termeth them in Latin after the Hebrew word, and all the oracles and answers of the gods were given in meter or verse, and published to the people by their direction.

And for that they were aged and grave men, and of much wisdom and experience in the affairs of the world, they were the first lawmakers to the people and the first politicians, devising all expedient means for the establishment of commonwealth, to hold and contain the people in order and duty by force and virtue of good and wholesome laws, made for the preservation of the public peace and tranquility. The same peradventure not purposely intended but greatly furthered by the awe of their gods and such scruple of conscience as the terrors of their late invented religion had led them into. (96–97)

Puttenham’s mythic history of the evolution of humanity has several episodes: there is the potential humanity before the poetic event of actualizing that potential; the poetic event itself; and the stages of development that follow—scientific, religious, legal, and political. It should be pointed out that this evolution is what language is for, according to Puttenham, who explains later that “language is given by nature to man for persuasion of others and aid of themselves” (98). Language is for human society, and it is an art: language is made by human beings for human beings. Before the world-historical event of language, we were rather unimpressive—really no more than animals—living in the wild, “vagrant and dispersed like the wild beasts, lawless and naked” (96). Because of our disordered “manner of life,” we “little differed . . . from the very beasts of the field.”

“Poetry actualizes in human nature its potential for the soul’s integrity and the city’s justice by reordering the soul and the city through poetic ordering.”

Puttenham recounts the foundational poetic event twice (and allows that there may have been others), first through Amphion and then through Orpheus, both of whose poetry is accompanied by the music of the harp. Amphion built the city of Thebes by moving and arranging stones through his poetic art; Orpheus gathered and tamed the animal kingdom through his. Building cities and taming nature are, for Puttenham, figures for the transformation of the human soul. Amphion mollifies the “hard and stony hearts by his sweet and eloquent persuasion”; Orpheus “brought the rude and savage people to a more civil and orderly life.” After that poetic transformation of the human soul, resulting accomplishments occur. The poets invent natural philosophy or science, then religion (since they move from the moved heavens to the first mover), making them “the first priests and ministers of the holy mysteries” and “the first prophets.” Afterwards, they become “the first lawmakers” and “the first politicians.”

A question arises: why is it that poetry does this and not merely rhetorical language per se? Language is the condition of possibility of sociality in Cicero, but Puttenham argues relentlessly that poetry is that condition. Why? Puttenham, as it becomes clear, believes that poetry’s artistic character of poetic ordering prepares the soul for participation in civil ordering and is somehow an analogy for it. His discussion of meter might make those who are not English majors roll their eyes and perhaps lead them from finishing a book on the history of prosody in Book 1, the formation of poetic stanza in Book 2, and the figures of speech in Book 3—the three books making up the whole of the treatise. We live in an era of prose, yet Puttenham defends verse:

But speech by meter is a kind of utterance more cleanly couched and more delicate to the ear than prose is, because it is more current and slipper upon the tongue, and withal tunable and melodious, as a kind of music, and therefore may be termed a musical speech or utterance, which cannot but please the hearer very well. Another cause is, for that it is briefer and more compendious and easier to bear away and be retained in memory, than that which is contained in multitude of words and full of tedious ambage and long periods. It is, beside, a manner of utterance more eloquent and rhetorical than the ordinary prose, which we use in our daily talk, because it is decked and set out with all manner of fresh colors and figures, which maketh that it sooner inveigleth the judgment of man and carrieth his opinion this way and that, whithersoever the heart by impression of the ear shall be most affectionately bent and directed. The utterance in prose is not of so great efficacy, because not only it is daily used, and by that occasion the ear is overglutted with it, but is also not so voluble and slipper upon the tongue, being wide and loose and nothing numerous, nor contrived into measures and sounded with so gallant and harmonical accents, nor, in fine, allowed that figurative conveyance nor so great license in choice of words and phrases as meter is.

So as the poets were also from the beginning the best persuaders and their eloquence the first rhetoric of the world, even so it became that the high mysteries of the gods should be revealed and taught by a manner of utterance and language of extraordinary phrase, and brief and compendious, and above all others sweet and civil as the metrical is.(98)

Poetry—language in verse and stanza and highly figurative language—is more measured and concise than prose, more memorable, and its musical compression is “sweet and civil.”

Why? Because the remembered poem’s ordering principles re-order the rememberer in sweetening and making more civil the soul of the one who learns poetry by heart. In the conclusion of the book, Puttenham argues that “art is an aid and coadjutor to nature” (382). If we bring that broad understanding back to Puttenham’s belief that poetry makes us human, we can see why. Poetry actualizes in human nature its potential for the soul’s integrity and the city’s justice by reordering the soul and the city through poetic ordering—metrical, stanzaic, and figurative. The poets may imitate human nature, and that is one of their derivative powers. Even so, they influence and alter raw human nature into civilized human nature. They are like gods in their power of making, not just imitating, and what they make is us.

This raises profound ethical questions, questions Puttenham does address. For now, it suffices to emphasize his hope for poetry:

Finally, because they did altogether endeavor to themselves to reduce the life of man to a certain method of good manners and made the first differences between virtue and vice, and then tempered all these knowledges and skills with the exercise of a delectable music by melodious instruments, which withal served them to delight their hearers and to call the people together by admiration to a plausible and virtuous conversation, therefore were they the first philosophers ethic and the first artificial musicians of the world. (99)

Poetry calls people as people together and is the primary art of the human world.

Allow me to conclude with a moment from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice.6 Shakespeare knew Puttenham’s book, published long before the play, and one can hear Puttenham’s myth in Lorenzo’s discussion of music with his new wife, Jessica. The whole exchange is rich and ethically complicated, as is the play, but Shakespeare gives Lorenzo a myth Puttenham would recognize, and he does so in poetry more beautiful and sweet than any of Puttenham’s prose:

How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!

Here will we sit and let the sounds of music

Creep in our ears. Soft stillness and the night

Become the touches of sweet harmony.

Sit, Jessica. Look how the floor of heaven

Is thick inlaid with patens of bright gold.

There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’st

But in his motion like an angel sings,

Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubins.

Such harmony is in immortal souls,

But whilst this muddy vesture of decay

Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it. (5.1.54–65)

Musicians enter:

Come, ho! and wake Diana with a hymn.

With sweetest touches pierce your mistress’ ear,

And draw her home with music.

The music plays, and, after Jessica discloses that she is “never merry when [she] hear[s] music,” Lorenzo begins his Puttenham-inflected myth:

The reason is, your spirits are attentive,

For do but note a wild and wanton herd

Or race of youthful and unhandled colts,

Fetching mad bounds, bellowing and neighing loud,

Which is the hot condition of their blood,

If they but hear perchance a trumpet sound,

Or any air of music touch their ears,

You shall perceive them make a mutual stand,

Their savage eyes turned to a modest gaze

By the sweet power of music. Therefore the poet

Did feign that Orpheus drew trees, stones, and floods,

Since naught so stockish, hard, and full of rage,

But music for the time doth change his nature.

The man that hath no music in himself,

Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,

Is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils;

The motions of his spirit are dull as night,

And his affections dark as Erebus.

Let no such man be trusted. Mark the music. (66–88)

The sweet power of poetry can change our nature and draw us home to ourselves and our associates. Again, Jessica’s troubled spirit darkens the festive close of a play whose festivity is underwritten by the ruin of her father.7 But, taking Lorenzo’s lines as a set-piece, we can see that English poetry’s most important poet and creating god of the human soul is well aware of his own poetic enterprise: the sweet harmony of the human being made in the home of poetry.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy