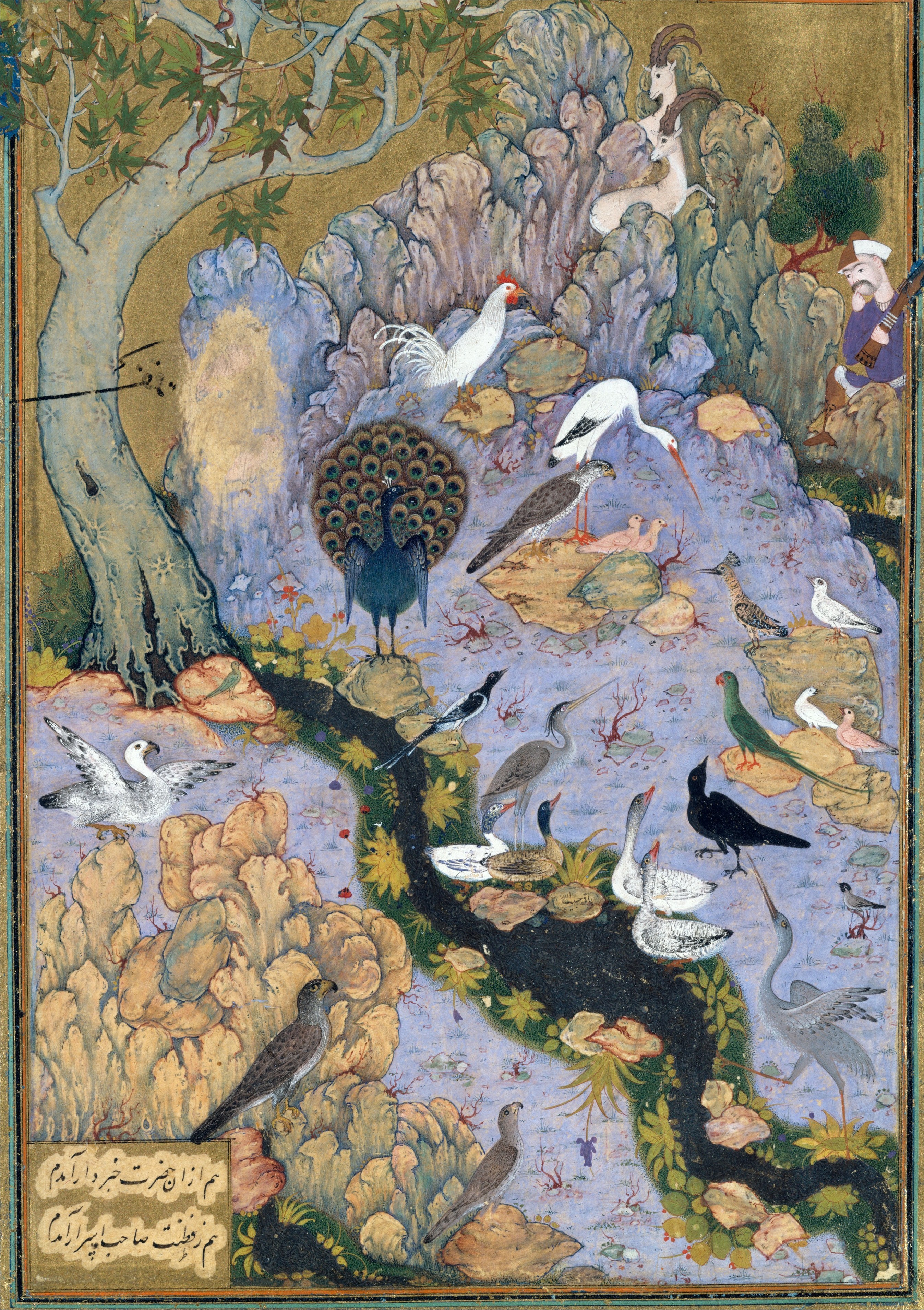

A folio from an illustrated manuscript of The Conference of the Birds, Habiballah of Sava, c. 1600

Marcus Aurelius and Farīd al-Dīn ¢Aţţār did not have much in common. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE) was a dour and stoical Stoic. Much of his time as emperor was spent campaigning against the barbarians on the northern frontiers of the empire during a reign enlivened by an internal revolt in Syria, a flood in Rome, a famine, and a plague. Farīd al-Dīn ¢Aţţār was a pharmacist and perfumer in Nishapur in northeastern Iran, a mystical poet of verve and wit, who lived from the mid-twelfth century to about 1220. The only things they really had in common were unfortunate encounters with barbarians from the north—¢Aţţār is thought to have been killed when the Mongols sacked Nishapur—and an intense concern with the meaning of life and how it should be led, which they each enshrined in brilliant books still well worth reading.

Marcus Aurelius was born to the purple, the nephew of one emperor and the adopted son of another. His name changed and acquired new additions through life, eventually becoming Imperator Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, along with various other titles, but since we know him best through his intensely personal collection of reflections, the Meditations, I will refer to him as Marcus. The chronicles of Rome record his official life. He received an excellent education, as befitted an intelligent member of the imperial family. His uncle, the Emperor Hadrian, spotted his talent while Marcus was still a teenager. Because his father had died, he was adopted by Emperor Antoninus Pius, who himself had been adopted by Hadrian. Adoption in this period had become the preferred mode of imperial succession, leading to a series of first-rate emperors, replacing the often messy modes of succession in the generations following Julius Caesar. With the death of Antoninus in 161, Marcus became co-emperor with Lucius Verus, another adopted son of Antoninus, who then died suddenly in 169, leaving Marcus as sole emperor, a position he held until his death on campaign in Vienna in 180. The last years of his life were mostly spent campaigning against invading Germanic tribes along Rome’s northern frontiers. His excellent education prepared him for the administrative work that flowed endlessly to him and that he seems to have handled with a competence and conscientiousness that earned him respect; this work probably accounts for the occasional complaints about lack of sleep found in his Meditations. His death and the succession of his erratic son Commodus marked the end of what Gibbon referred to as the most happy and prosperous time in the history of the world.

Marcus, much to the dismay of Fronto, his distinguished tutor in Latin rhetoric, “converted” to philosophy. He was, in fact, the last significant member of the Stoic school, one of the several schools of thought that competed for the legacy of Socrates and Plato during the centuries after their deaths. The Stoics were, well, stoics. Though they made major contributions to logic, physics, and metaphysics in works that survive only in fragments, we know them best through the surviving ethical works of the Roman Stoics Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus himself. The stern Stoic notions of duty and indifference to pleasure and pain live on through certain aspects of Christian ethical ideals and through the republican virtues of the American founding fathers. They certainly fit the needs of a soldier-emperor such as Marcus.

So what of the Meditations? They are a series of several hundred disconnected jottings, ranging from a couple of lines to a page or so. Marcus seems to have begun the work soon after he became emperor and added to it from time to time. It is written in excellent Greek but, despite obvious care in its composition, was evidently not intended for publication; indeed, its proper Greek title is τὰ εἰς ἑαυτὸν ἠθικά (Ethics, to himself). If it was written in the order we now have it, it may have started as an attempt to take stock of his life, since the first book (of twelve) is devoted to an accounting of those people and circumstances for which he was grateful, generally for their role in shaping his education and character. It disappeared from history until an early-tenth-century bishop and bibliophile had a fresh copy made of a manuscript “so old indeed that it is altogether falling to pieces” and sent it to a friend. This copy is the basis of every known manuscript.

The Meditations are intensely personal, often expressing dissatisfaction with the author’s own failures to live up to his Stoic ideals. Although Marcus does not have much to say about his role as emperor, it is implicitly present on every page. Perhaps it is anachronistic to imagine that Marcus saw his role as holding off the inevitable triumph of barbarism for another generation, though that is what he did. He certainly does mention the classic Stoic doctrine that pleasure, pain, and worldly fortune and misfortune are matters of fundamental indifference, to be ignored by the rational soul. The more common theme of the Meditations is how to be a good man, “to rise in the morning and do the work of a man.” The world, Marcus insists, following his Stoic masters, is a harmonious whole, made so by God, or Nature; Nature and God seem to be more or less the same for Marcus. A man’s nature is to be good and to play his part in the whole, the whole sometimes being society and more often the universe as a totality. One must therefore love one’s fellow men, something Marcus frequently chides himself for failing to do. Not only does his position as emperor expose him to the worst of human character, but his own temperament is decidedly ascetic, to the edge of misanthropy. Indeed, several short entries consist solely of a series of insults obviously directed at an unnamed individual who had drawn his ire.

Bust of Marcus Aurelius in the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul, Turkey; photo: Eric Gaba / Wikimedia Commons

Marcus’s ethics are of this world, which seems appropriate since, as emperor, his chief duty was toward this world. For him, the “work of a man” is work for the well-being of other men. Although he insists on the perfection of the universe, he generally does so as a way of telling himself that seeming evils ultimately are a matter of indifference, because what seems evil to the individual may be good in the context of the universe as a whole. Thus, pleasure and pain are matters of rational indifference, probably the most notorious Stoic doctrine.

Death preoccupied him. He had seen much death and realized that his own death might not be distant. It is not to be feared, he insisted over and over. Even the longest life is a fleeting moment. Whether death is dissolution into atoms or something else, it is a relief from the trials of life and, as a function of Nature, not to be feared. For any man, no matter how great or famous, in a short time, all who knew him will be gone, and soon after, all memory of him will be lost and his achievements forgotten.

What are we to make of the Meditations? It is obviously the work of a noble spirit and a tired man—a man worn down by responsibilities and endless work but determined to live up to a demanding code. It offers an ethic of this world for those with responsibilities to this world. That and the appeal of Marcus’s earnest quest to be a good man have kept this work—written late at night, in fragments, on the frontier of an empire about to begin its decline—fresh and appealing almost two millennia later.

A thousand years later and five thousand kilometers to the east, the druggist and perfumer Farīd al-Dīn ¢Aţţār wrote his epic poem The Conference of the Birds (Manţiq al-ţayr), a classic of the literature of Sufism (Islamic mysticism). Considering that Marcus and Attar shared an intense concern with the same topic—how human beings should lead the good life—the books they wrote could scarcely be more different or reflect more different personalities. If Marcus had not been a Stoic, we should certainly have called him stoic, and if he had a sense of humor, he left no trace of it in his Meditations. On the other hand, ¢Aţţār was a lively writer and a wit, for The Conference of the Birds, though a spiritual classic, is a very funny book. Whereas Marcus sternly rebukes himself for his failings, the characters in the little tales that fill ¢Aţţār’s book enlighten us by their amusing predicaments.

The Conference of the Birds is a charming allegory whose frame story might have been told in a few hundred lines, but ¢Aţţār constantly interrupts the narration with anecdotes, ranging in length from a few lines to twenty pages, generally followed by a few lines explaining the moral of the story. The poem is written in lively rhymed couplets, suited to the brisk and witty tone of the narrative. In the frame story, from which the book takes its title, the birds notice that they alone of the kingdoms of the world do not have a king. When they meet to discuss the problem, the hoopoe1 takes the chair and explains that they do indeed have a king: the immortal phoenix, the Simorgh, who lives on Mount Qāf, at the edge of the world. They need only go and pay their allegiance to him. At that point, the birds, each of whom represents a human type, begin to make their excuses, and are in turn answered by the hoopoe. In due course, the birds set out, suffering hardships that lead to most of the birds either perishing or turning back; however, when the thirty remaining birds reach the Simorgh’s palace, they are turned away by a herald. Eventually the herald grudgingly admits them, but he also presents them with a document detailing all their sins. Purified by humiliation, they finally realize that they, the thirty birds—sī morgh in Persian—are themselves the Simorgh.

On their journey, the birds pass through seven valleys: seeking, love, knowledge, detachment, unity, wonderment, and poverty and annihilation. These are ¢Aţţār’s version of the stages of the mystical life, as found in every mystical tradition. It is tempting to talk in detail about the flawed human types represented by the various species of birds answered by the hoopoe before they set out: earthly love, greed, pride, false humility, and so on. However, two much more basic themes run through the book: the rejection of the lower self and the necessity of love. A few examples illustrate the former: a miser is reborn as a mouse in his own house, tormented by the thought that no one is guarding his hoard of money; two Sufis who are parties to a lawsuit are rebuked by the judge, who points out that if they can afford lawyers’ fees, they can’t truly be men of spiritual poverty; a fly pays with his only possession (a grain of barley) to be carried to a beehive, where he becomes mired in the honey and regrets his folly. In addition, the book is replete with stories of lovers, such as the Sufi moved to sorrow about his own state by the sight of a woman grieving by her daughter’s grave because she knew, which he did not, the object of her love. Joseph, whose beauty moved Potiphar’s wife to reckless passion, appears more often than any other character in the book. Greatest and longest of all is ¢Aţţār’s tale of Shaykh Śan¢ān, the elderly religious scholar who had made fifty pilgrimages and was the recognized master of four hundred students. He is inspired by a dream to go to Rome, where instead of converting the populace to the true faith, he becomes enamored of a beautiful Christian girl, at whose whim he becomes a Christian, worships the cross, and tends her pigs.

The Conference of the Birds is not exactly a guide to the mystical life but rather an advertisement for it. There are carefully written Sufi manuals to guide masters and disciples on the path, but this is not one of them. Like other masterpieces of art and literature, it works on many levels, including amusement and aesthetic pleasure, but most fundamentally, it serves as a rebuke and reminder of what is truly important. You may chuckle at the folly of a character in one of the anecdotes, only to realize you are looking at yourself.

These two books have much in common. They are written by two men who believed no concern is more urgent and pressing than to know the proper way for human beings to live their lives. These are thus books that one might return to over and over in the course of a long life, finding new lessons to ponder each time. Both men are intensely concerned with death and the ephemeral nature of all things human, though ¢Aţţār, who probably wrote his book around age forty and who was quite clear about the nature of the afterlife, viewed it rather more lightly than did Marcus, for whom death was a looming presence whose outcome he did not know with any certainty. One senses that he was steeling himself for death like a soldier preparing for battle. Both authors were firmly convinced that the things of this world, however attractive they might seem, and however providential the arrangement of nature might be, were a distraction to be ignored as much as possible. One can without difficulty find ¢Aţţār’s seven valleys in Marcus’s private struggle with his soul.

There are differences too. Marcus, though he strives for a Stoic indifference to the pleasures and pains of the world, offers us an ethic for this world. He makes no claim to know what is beyond this life, merely saying that, one way or another, death is not to be feared. Moreover, even though he frequently stresses the importance of venerating the gods, or the God, he does not convey much about spirituality. Finally, Marcus does not share ¢Aţţār’s belief in the centrality of love. However much Marcus might honor the gods, he does not claim to love them. He does talk about the duty to love one’s fellow men, but he frankly admits he does not enjoy it. The only people he really seems to like are craftsmen, whose dedication to their crafts—so different from the idleness of the courtiers who surround him—he sincerely admires. His love for humanity is expressed in his conscientious attention to his duties as emperor; nothing in his soul is remotely like the exuberant delight ¢Aţţār clearly takes in the foibles of humanity. ¢Aţţār’s path is no easier than Marcus’s, but it would seem to be more fun, and is certainly more fun to read about.

In one thing ¢Aţţār was clearly right and Marcus wrong. Whereas Marcus repeatedly returns to the theme of the perishability of all human things and the fact that great men and their deeds will soon be forgotten, ¢Aţţār boasts that his book will live until Judgment Day. Marcus’s book, whether he ever intended anyone else to read it or not, has endured for almost two millennia and still speaks as clearly as ever to earnest people. ¢Aţţār’s book is as fresh and appealing as it ever was. I doubt either will soon be forgotten.

Translated by Martin Hammond (Penguin Classics, 2014)

There are many translations of the Meditations. I have used the translation of Martin Hammond (New York: Penguin Classics, 2014), which was done in sober modern prose, without archaisms, and which has a good introduction by Diskin Clay and notes on almost every paragraph. This is a nicely produced compact hardbound edition—“suitable for carrying in one’s pocket while on campaign,” as Marcus might suggest.

Buy NowTranslated by Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (Penguin Classics, 2011)

For ¢Aţţār’s The Conference of the Birds, I have used the revised translation by Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis (New York: Penguin Classics, 2011). This edition contains ¢Aţţār’s introduction and epilogue, which were omitted in the original 1984 edition. The translation uses rhymed heroic pentameter couplets modeled on Dryden but without the archaisms of many older translations of Persian poetry. I have also referred to the translation by Sholeh Wolpé (New York: W. W. Norton, 2017), which employs blank verse for the frame story and the moralizing passages and prose for the anecdotes. It omits the poem’s introduction. A number of other translations, old and new, exist, but I did not use them while writing this. Personally, I prefer the Darbandi-Davis translation, which seems to me a remarkable achievement in reproducing the content and style of the original, but tastes in both poetry and translation vary dangerously.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy