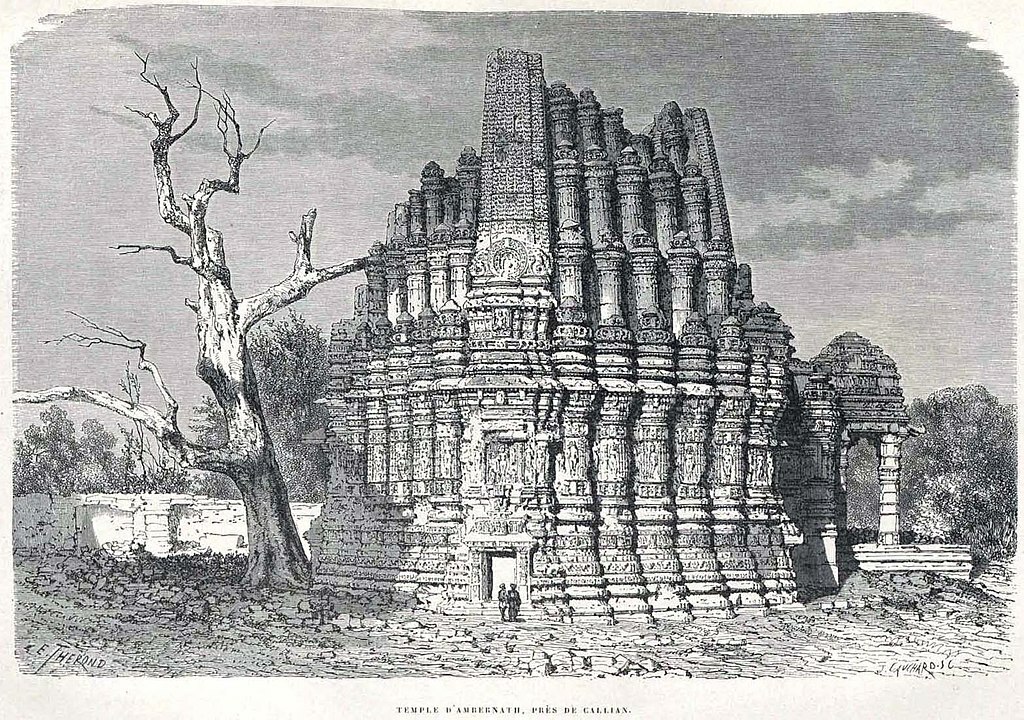

Drawing of the Shiv Mandir of Ambarnath, an eleventh-century Hindu temple in Maharashtra, India / Wikimedia Commons

Across the different religious traditions of the world, a recurring question relates to the type and the measure of similarity between humanity and divinity that can be coherently articulated. To begin with, the divine reality is not just my uncle who is a mortal being subject to the limitations of finitude. However, these religious traditions have also claimed that the divine presence can become vividly expressed in, illuminated by, or refracted through certain human beings—guru, avatāra, prophet, rabbi, and (the) incarnation. How do we imagine this “point of contact” without implying that divinity is simply a magnified version of humanity, in which case we may be tempted to imagine God as a Superman who flies through the sky at an astonishing speed?

During the years when I was in junior school in Assam, India, I did not know that I would someday spend much of my time exploring such questions relating to the religious imagination, yet I must have been unselfconsciously imbibing certain notions of divinity from my socioreligious atmosphere. In those days, most people around me were Hindus, and some family friends and relatives (through interreligious marriage) were Muslims and Roman Catholics. Across these Hindu-Catholic and Indo-Islamic borderlines, I was dimly aware of discussions relating to whether God1 has a specific form or is utterly formless and whether God has become known to us through some medium or God has no intermediary, and I could vaguely sense that these “theological” questions were pretty important to the grownups around me.

Around this time, I started receiving formal instruction in singing the devotional songs composed by the poet-thinker Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). During a Hindu festival of the goddess (devī), my teacher asked me about my plans for the day. I must have given her a puzzled look, and I clearly remember her response. She paused for a moment, peered into my eyes, and declared in Bengali: “ki? thākur dekhte jābe nā tumi?” I will translate her sense of dismay, etched onto my mindscape, literally: “What?! You will not go to see God [thākur]?”

Today, I study Hindu conceptions of the deity, and I reflect on them in conversation with Islamic and Christian conceptions. In these conceptual engagements, I often feel struck—once again—by the visual force of the verbal form dekhte, derived from the infinitive dekhā, “to see.” That I could be so insouciant on a day of the festival that I did not even consider going out to see God was unthinkable to my music teacher. But a critic may claim that precisely this aspiration is shot through with “idolatry”—the human attempt to see God domesticates the boundless divine within a human cognitive compass by elevating a spatiotemporal object constructed with human hands to the status of the eternal. Here, by “critic” I don’t mean just an Abrahamic theologian. For centuries, Jewish, Muslim, and Christian thinkers have indeed grappled with the question of idolatry. What I wish to explore is the theological significance of a somewhat lesser-known fact—that Hindu traditions (also) abound with critics of attempts to re-present the divine through human forms. Over roughly two millennia, both sides of this debate have developed sophisticated arrays of arguments regarding the nature of the divine reality. Abrahamic theologians may find in these arguments some fruitful resources with which to reflect on, and rethink, the concept of idolatry in their distinctive scriptural contexts.

What we refer to as “Hinduism” is a sprawling labyrinth of multiple socioreligious routes, some crisscrossing and some sharply divergent, that have been developing in South Asia over three millennia. So that we do not lose our way in this dense matrix, I will offer as a guiding thread some reflections on a particular theological dilemma that is embodied in a famous narrative in a scriptural text, the Bhāgavata Purāṇa (ca. 900 CE), and in an equally famous vision sketched in another scriptural text, the Bhagavad Gītā (ca. 200 CE). The divine reality at the center of these texts is Kṛṣṇa (Krishna), and the worship of Kṛṣṇa—as the one true source, foundation, and telos of the finite world—has been foundational to many Hindu worldviews in premodern South Asia as well as in contemporary India and diasporic locations.

The dilemma may be sketched out in this way. On the one hand, a meaningful relationship with God—in the form of praise, worship, adoration, or communion—presupposes, at the very least, our ability to speak about God. If God is so radically other that nothing whatsoever can be conceptualized or uttered about God, our only response would be an unmitigated silence. On the other hand, because our speech is interwoven with our human finitude, the cultivation of a relationship with God is already inflected with a form of cognitive objectification. More precisely, the dilemma we have to navigate involves trying to say something about God without reducing God to the status of something. A via media through the horns of this dilemma would be the difficult discipline of an existential equipoise in which our claims of knowing God are informed by our heightened awareness of unknowing God. God is the ever-receding horizon toward which we walk, while it is God’s spiritual gravitation that impels us to embark on this journey in the first place. So, God can be spoken of only through an eloquent silence—to say something about God is to unsay it.