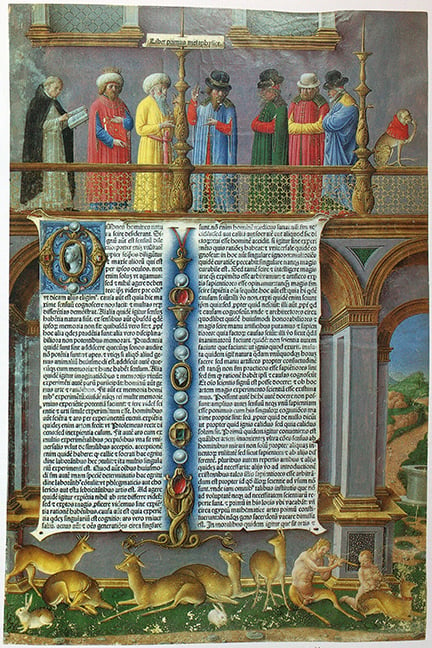

The beginning of Aristotle’s “Metaphysics,” showing philosophers in conversation, with an ape at right, as a counterpole, 1483

The intellectual legacy of Abrahamic religion is incomplete without natural theology, the soft-boundaried yet discernible enterprise of rational inquiry about the existence and nature of God, and indeed the natural world insofar as it is related to God. Arguments from (for example) Ibn Sīnā, Anselm, Ghazālī, and Aquinas enjoy regular attention even in contemporary philosophy of religion—so much so that it is difficult to imagine the discipline without them. But even if natural theology has always faced critics “from the inside” of the traditions for which it is ostensibly a servant, in secular Western democracies today its principal foil is surely naturalism, the view that “reality is exhausted by nature, containing nothing ‘supernatural.’”1 On naturalism, it’s not just that arguments of the abovementioned sort are unsound; it’s that the very methods of natural theology must be rejected, especially insofar as they involve appeals to evidentiary standards that lie beyond the remit of the empirical sciences.2 While debates do rage in subfields such as metaphysics and the philosophy of religion, naturalism enjoys preeminence in anglophone philosophy departments writ large, having achieved the rare feat of persuading a sizable majority of philosophers.3 Naturalism is its own traditio, with which mainstream philosophical and scientific academies are entrusted to hand on to their students. In these institutions, naturalism is not just a reflective answer to certain questions of metaphysics or the philosophy of science but also something like a broader academic “paradigm.”4 Naturalism is “how things are done around here.”

My purposes herein do not concern the soundness of particular arguments in natural theology, though perhaps it is not so inconspicuous that I do hold many of them in high regard. Instead, I want to ask and attempt to answer another question—one that pertains to naturalism as a paradigm of intellectual culture: Is naturalism ideology?

Some preliminaries first. By “ideology,” I do not mean some abstract idea or system of ideas that is independent from and innocent of the social lives of those who might consider its merits in a seminar room. I mean instead something like what Karl Marx meant when he spoke of a “German ideology”—that is, an institutionally dominant “production of ideas, of conceptions, of [false] consciousness”5 that is systematically ordered toward the legitimation of the concrete social relations of a given historical moment. Ideology in this pejorative sense involves two specific, signature misrepresentations: (1) a misrepresentation of what is really only in the interest of a particular social group as being in the interests of people in general, and (2) a misrepresentation of what is contingent and historically specific as though it were necessary. To use Brian Leiter’s terms, these are the “Interests Mistake” and the “Necessity Mistake,” respectively.6 Ideology always involves certain core false or unwarranted judgments that are implied in these two signature misrepresentations. The interesting thing is not just that ideologies misrepresent—it’s how they misrepresent.

I think that the case for the ideological character of naturalism turns out to be rather surprisingly strong. Although critics of naturalism tend to be skittish of such claims about ideology given certain commitments of their progenitor, one need not be some sort of committed “historical materialist” to see the point here: if it is possible for institutionally dominant ideas to misrepresent in these socially relevant ways—and surely it is—then something like ideology in the Marxian sense is possible and perhaps even likely. For naturalism, the shoe fits surprisingly well.

First things first: ideology gives shape not just to any consciousness, but false consciousness. Does naturalism satisfy this description? In an admirably frank paper published recently in the journal Philosophy, Thomas Raleigh offers some reasons to think so:

I used to spend a fair amount of time thinking and worrying about naturalism. In particular, I used to think it was an important philosophical question.… [But] “naturalism” is really no more than an empty term of approbation that philosophers tend to bestow on theories that they find plausible and withhold from those they find implausible. The methodological moral I suggest we draw is that we should just stop talking about naturalism entirely—at least when doing serious first-order theorising in philosophy.7

Why this deconversion? I won’t rehash the entirety of Raleigh’s argument (which is worth reading in full), but it’s worth emphasizing a couple of salient points.

If by “naturalism” we mean the metaphysical thesis that only natural things exist, then it is hard to see what the descriptor “natural” adds to our understanding of anything, or even what it would mean to hold the opposite, “supernaturalist” view. To illustrate, Raleigh asks us to consider a thought experiment involving some future, credibly scientific, empirical discovery of real, causally efficacious ghosts. Much to our surprise, the thought goes, these ghosts have turned out to be observable and to have certain bizarre properties that do not fit well with our previous understanding of the natural world. What would a card-carrying naturalist’s response to this surprising discovery be? Would it count as evidence against naturalism as a metaphysical thesis?

It seems like it should, since one of the principal motivations for being a naturalist in the first place is to exclude “weird,” “spooky,” or “immaterial” things from one’s world. Yet, as Raleigh notes, were this to happen, “there would not be any point in asking whether ghosts are ‘natural’ or ‘supernatural’.… Once we admit that they are part of reality, what further possible theoretical interest would be served by asserting or denying that they are part of ‘nature’?”8 In other words, would we take such a discovery to falsify naturalism, or would we take it as a particularly surprising broadening of our conception of what constitutes the natural world?9 Raleigh’s point is that there is no good way to tell and, thus, naturalism as a metaphysical thesis is fatuous. Unless we have in advance some specifying and thus limiting conditions for what counts as “natural,” naturalism as a metaphysical thesis has no content or real claim on anything. It’s empty.

But a more lightweight, “methodological” (as opposed to metaphysical) conception of naturalism fares no better, according to Raleigh. If naturalism simply means (for example) that “scientific inquiry is our only legitimate form of inquiry,”10 then we’ve relieved the burden from the term “natural” only by shifting it rather conspicuously to the term “scientific.” But of course the so-called demarcation problem (i.e., the problem of demarcating scientific from nonscientific theories in a principled way) in the philosophy of science is notoriously difficult. Broad appeals to empirical access or observation will not do the trick, since many credibly physical theories, including the most successful ones, regularly reference non-observable entities. Indeed, as Raleigh points out, Isaac Newton’s theory of gravitation was initially rejected on account of its failure to limit itself to certain “mechanistic” accounts of causal explanation. It was a “spooky” theory, even though we recognize it today as among the greatest of all scientific discoveries.11 And the situation becomes even more hopeless when considering the science of mathematics, whose proper subject matter arguably involves few if any observables at all. In other words, if Newtonian physics and modern mathematics don’t get to count as sciences, then we need to rethink our criteria.

All in all, methodological naturalism does not seem to fare much better than its brasher metaphysical counterpart.12 As Bradley Monton puts it in a widely cited essay,

If science really is permanently committed to methodological naturalism, it follows that the aim of science is not generating true theories. Instead, the aim of science would be something like: generating the best theories that can be formulated subject to the restriction that the theories are naturalistic.… I maintain that science is better off without being shackled by methodological naturalism.13

It should be pretty clear what the point is here: naturalism faces very serious challenges, not just with respect to its truth or warrant, but even with respect to its meaningfulness as a paradigm. Naturalism has an “emptiness” problem. But does it have an ideology problem as well?