Lear and Cordelia, Ford Madox Brown, c. 1850

I’m Nobody. Who are you?

Are you—Nobody—too?

—Emily Dickinson

I begin with a truth lived out in tragedy and life: we must suffer into wisdom. As articulated by Aeschylus’s Chorus in the first play of the Oresteia, “Zeus who set mortals on the road / to understanding… made ‘learning by suffering’ into an effective law.”1That law is pathei mathos, “learning by suffering.” Of course, we might simply suffer, drawing no wisdom from it other than the desire to stop our suffering. In this time of plague, many of us simply want the suffering to end. Suffering is not enough for learning to occur, though. We will need to reflect upon it, and literature is perhaps our best means to do so.

What is the wisdom of King Lear, Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy, and is it the same as the wisdom of the beatitudes as they appear in Jesus’s greatest discourse? Could Lear’s pathei mathos be better understood through gospel wisdom? What does the first beatitude in particular mean, and does it help explain how Lear’s suffering through the loss of “accommodation” transforms him into a more ethical human being?

Shakespeare’s relationship with the English Bible of the early modern period is rich and strange. He probably read the Geneva translation of the Bible and its Protestant commentary, but heard the Bishop’s Bible at church, both of which were forerunners of the King James Bible, the great English Bible so influential upon Anglophone literature for the last four hundred years.2 But Shakespeare uses the Bible the way he uses other sources. As a literary artist inspired by any other text, he imitates but innovates upon what he is imitating, often transforming his source. I will not put the beatitude next to the play as a key to unlock the play, though it does so to a degree; instead, I will put the two into dialogue with one another. Shakespeare goes a long way with the Christian tradition’s understanding of the beatitude, but he augments that tradition, as we will see, by questioning it.3

Here is the beatitude from Matthew 5.3 in Greek, Latin, and contemporary English:

Makarioi hoi ptôkhoi tô pneumati,

hoti autôn estin hê basileia tôn ouranôn.

Beati pauperes spiritu

quoniam ipsorum est regnum caelorum.

Blessed are the poor in spirit,

for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.4

If and when Shakespeare opened his Geneva Bible, he would have seen the first beatitude looking like this: “Blessed are the poore in spirit, for theirs is the kingdome of heauen” (5.3).5 The first beatitude in Matthew’s formulation is the foundation of the seven beatitudes that follow—concerning those who mourn, those who are meek, those who desire righteousness, those who are merciful, those who are pure in heart, those who are peacemakers, and those who suffer persecution (5.4–5.12)—all of which make up an introduction to the Sermon on the Mount, which is the central ethical teaching of the gospel of Matthew and of Christianity itself.6 Since it will be my argument that Lear becomes poor in spirit, I need to explore the beatitude in detail.

What does the beatitude mean? That question is more difficult here than in the gospel of Luke, where its formulation in the Sermon on the Plain is simpler (if still not simple): “Blessed be ye poore: for yours is the kingdome of God” (6.20). The “poor” are hoi ptôkhoi, those so destitute that they would have to beg, and the Vulgate translation, pauperes, seems right to me. Leaving aside other differences, I find Matthew’s distinct form of poverty, “the poor in spirit,” compelling even if not immediately clear. The material poverty of Luke is presumed by the spiritual poverty of Matthew, perhaps a necessary but not sufficient condition for it, but spiritual poverty is clearly something more. The material poverty of poverty is still central. As Servais Pinckaers reminds us, “the lack of material goods and wealth” is “that fundamental poverty, a universal human experience, which is the primary object of Gospel blessedness.”7

Pinckaers describes the materially poor person with acuity and compassion:

The poor man is affected in his basic need for food, clothing, housing, work, a future. His difficulty increases when poverty strikes those he loves as well, and gives rise to fears for their future. He is at the mercy of the unexpected, and all of this is often accompanied by sickness, loneliness, and quarreling. It has to be endured over long stretches, since there is no end in view. It keeps the poor man in obscurity, an object of misunderstanding, lack of consideration, scorn and injustice on the part of the powerful and well-off. It even jeopardizes his honor. Poverty causes profound psychological wounds that mark a man for life, because it attacks his self-esteem and drains his strength. (42)

One sees that material poverty quickly has physical, psychological, familial, and political consequences for the poor person. Pinckaers argues that material and spiritual poverty are more intertwined than people allow and that there is an opportunity in poverty to discover, experience, and be improved if the poverty is accepted: “The poor in spirit are those who have the courage to accept this presence in their lives and come to love it” (43). Why and how would anyone love poverty? Pinckaers:

However varying the forms of poverty may take, they all interconnect and lead us into that fundamental emptiness which lies at the depths of our being: the consciousness of our condition as creatures. We did not make ourselves. All that we have and are comes from another, and will be taken away from us some day, whether we wish it or not. We cannot stop the flow of time even for one instant; we can hold onto nothing as our own. This is the primordial poverty, the central void. (46, emphasis added)

“That fundamental emptiness which lies at the depths of our being”: we might come to love poverty because it is our elemental condition as ultimately and utterly fragile beings, and the acceptance of that fragility might open an otherwise closed soul: “Poverty places us at a crossroads. We can rebel and choose refusal and self-reliance—and this will harden us—or we can accept the suffering and let ourselves be shaped by poverty as we open ourselves to God and others. The decision is crucial” (47). Poverty becomes the occasion for an opening of ourselves “to God and others,” which is itself the occasion for love: the love of God and neighbor that is the central teaching of Jesus in Matthew. When one of the Pharisees asks Jesus for the greatest of the commandments of the Law, he replies, “Thou shalt loue the Lord thy God with all thine heart, with all thy soule, and with all thy minde. This is the first and the great commandment. And the second is vnto this, Thou shalt loue thy neighbor as thy selfe. On these two commandments hangeth the whole Law, and the Prophets” (22.37–40). And when Paul introduces the Christian virtues of faith, hope, and love, he confirms the last’s primacy: “the chiefest of these is loue,” or agapê (1 Corinthians 13.13). According to Pinckaers, poverty prepares us for love. Indeed, “there is no true love without poverty” (49). Since my argument is that Lear’s poverty of spirit will teach him to love, I would like to understand what love is in the sermon.

Love’s primacy is the essential but missing premise in this and the other beatitudes: the poor in spirit are blessed because the love they learn in that poverty is the one experience and act that brings them the kingdom.8 What is love?9 We might profitably begin with Aristotle on friendship, or philia (one form of love), in the Nicomachean Ethics, when he argues that friends wish their friends well for the friends’ sake, and such wishing is mutual and known to be so (8.2.4). Love is the wish for the good of the other. That definition informs Paul’s definition-through-attributes of love in 1 Corinthians 13: “Loue suffreth long: it is bountifull: loue enuieth not: loue doesth not boast it selfe: it is not puffed vp: It doeth no vncomely thing: it seeketh not her owne things” (4–5, emphasis added).

The Christian gospel adds at least two other elements to that high pagan love of philia for it to attain the status of agapê. First, the love of the human other must be informed by and is dependent upon the love of the divine other: love of neighbor depends upon love of God, the second commandment reliant upon the first. Second, the love of both the human and the divine other must eventuate in the sacrifice of one’s own good for the good of the other: “Loue suffreth long.” Christianity transforms ancient love through divine involvement and human self-sacrifice, and nowhere is that seen as clearly as in the person and action of the character who is the rhetor of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus himself, who is the human incarnation of the divine sacrificing himself for those he loves to achieve their flourishing, here blessedness, the blessedness of participation in the kingdom of heaven.

What is blessedness? The blessed are the makarioi, those who are “happy,” but that happiness must be thought of in two distinct ways: the happiness that is blessed is the highest form of happiness, and it results not only from one’s own actions but also from what one receives from God, both in the present and in the future. Human flourishing results from human virtue and divine blessing. Jonathan T. Pennington even translates the first beatitude thus to keep us from too forcefully separating classical and Christian ethics: “Flourishing are the poor in spirit because the kingdom of heaven is theirs.”10 The translation arises out of his conviction that the two cultural matrices of the Beatitudes are the pagan philosophical tradition of virtue ethics and the messianic religious one of Judaism (19–85). The beatitudes “present true human flourishing as entailing suffering as Jesus’ disciples await God’s coming kingdom that Jesus is inaugurating” (153).

That kingdom or basileia has a double aspect within what Christian theologians call the eschatological, the “already” and the “as yet” kingdoms. The kingdom is the blessedness a human being “already” has by participating in the divinely inspired activity of love on earth; the kingdom is also the blessedness a human being will—but not “as yet”—have by participating in that same activity in heaven. Matthew is clear that the kingdom will be fulfilled when Christ returns to judge human beings: “Then shall ye king say to them on his right hand, Come ye blessed of my father: take the inheritance of the kingdome prepared for you from the foundation of the world” (25.34). The “already” kingdom is less obvious but seems to be the fellowship or polity of disciples—those who see themselves as this king’s subjects and activate the new virtue ethic inaugurated by him. At its best, the church would be such a polity. As Jesus recommends in the Lord’s Prayer, “Thy Kingdome come. Thy will be done euen in earth, as it is in heauen” (6.10). That disciples will be rewarded eschatologically is a matter of faith. That they are being rewarded while suffering—in the terms of the first beatitude, the kingdom of heaven is theirs during their material and spiritual poverty—is also a matter of faith, but arguably, an even greater one since the poor are, almost by definition, not flourishing.

For a Shakespearean example, the deities in Prospero’s masque in The Tempest—a play that takes up so many of the questions of our play, but in the key of romance, not that of tragedy—wish for his daughter and her new fiancé not poverty but bounty, as Ceres makes so very clear in her song to the lovers:

Spring come to you at the farthest,

In the very end of harvest.

Scarcity and want shall shun you,

Ceres blessing so is on you.11

It is difficult to imagine a good father wishing poverty upon his children so they might be blessed. Be that as it may, according to gospel wisdom, the virtue of poverty is its own reward now, and it will be rewarded later.

What does the beatitude have to do with King Lear? When Shakespeareans approach the play with the Bible in mind, they tend to draw upon Job, understandably, since the play’s action takes place in a pre-Christian England (governed, apparently, by the Latin pagan deities), and Shakespeare is clearly engaging Job.12 But the play also represents its titular character becoming poor in spirit, acquiring the virtue of love, and entering temporary blessedness—a blessedness that comes apart, though, in such a way as to interrogate and be interrogated by the eschatological kingdom.13 Is the play Christian or not? The answer to that question depends upon how one reads the relationship between the beatitude and the play.

How does King Lear become poor in spirit? We see another language for poverty of spirit in Lear’s exchange with Poor Tom, the role Edgar plays in disguise as he hides to avoid Edmund’s plot against him, a beggar whom Lear sees naked and exposed to the elements, just before the exiled king strips bare to join him in his state:

Is man no more than this? Consider him well. Thou ow’st no worm the silk, the beast no hide, the sheep no wool, the cat no perfume. Here’s three on’s us are sophisticated [Kent, the Fool and Lear himself]; thou art the thing itself. Unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor, bare, forked animal as thou art. Off, off, you lendings, some, unbutton here.14

The natural human being without the “accommodation” of culture—what once was known as “habiliment”—is a poor animal, “the thing itself” in all of its vulnerability as it encounters what Pinckaers calls our “central void.” By this point in the middle of the play’s action, Lear is close to unaccommodated himself.

Lear certainly is not poor in spirit at the play’s beginning, though. He rules the kingdom, not of heaven but of earth. He has the authority to give that kingdom to his daughters; he maintains a retinue of followers; he has three apparently dutiful daughters; he is in his right mind; and he has housing, clothing, and food. We know he has these attributes of “accommodation” because we see him lose them all from his tragic error of dividing the kingdom—an ethical and political error since it assumes, as we shall see, that love can be measured without familial pretense and that a polity can be divided without civil strife, an error that irrevocably reverses his fortune. Lear recognizes that error very early in the play (“I did her wrong” [1.5.25]) as he begins to suffer from that reversal.15

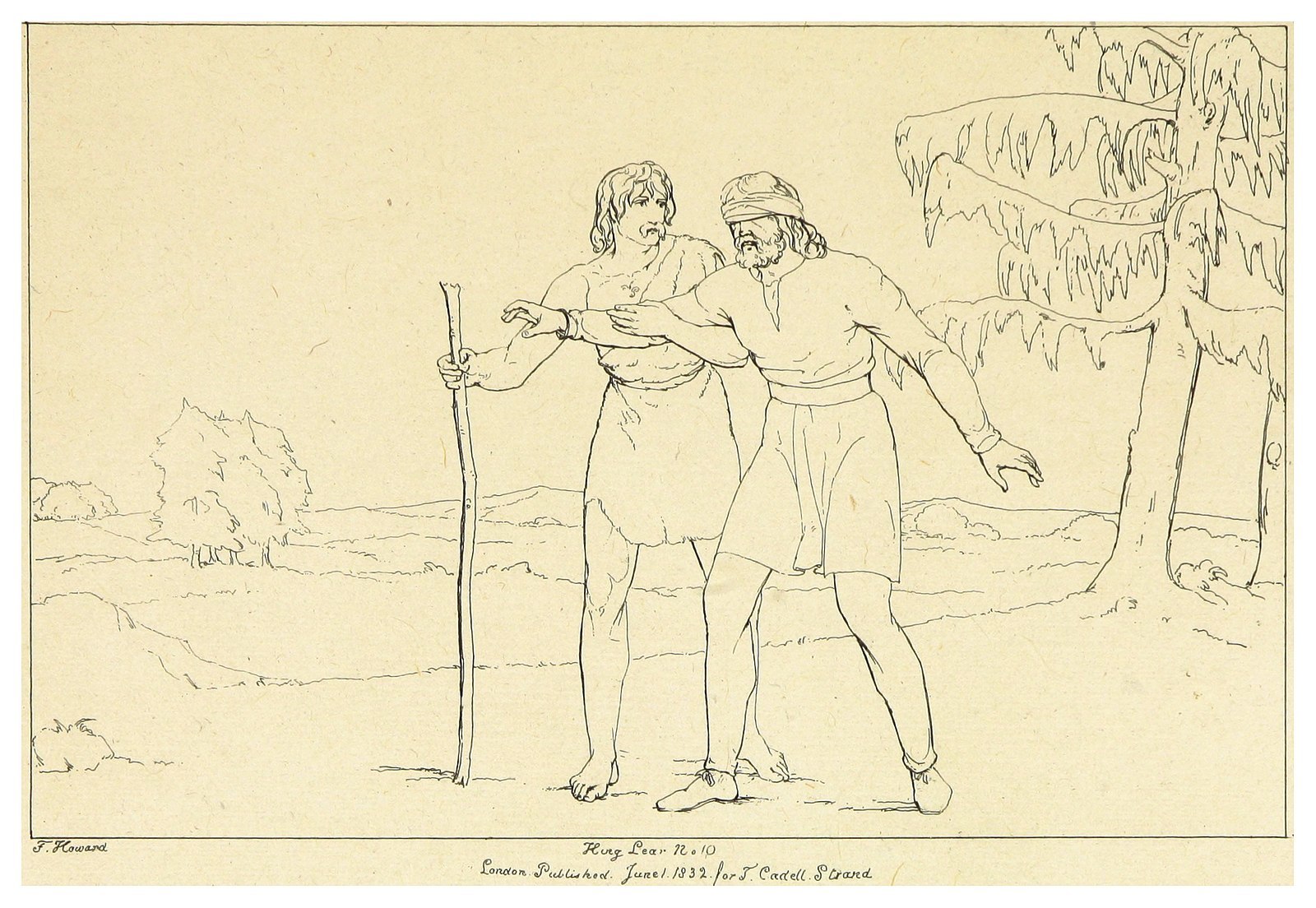

King Lear as depicted in an illustration by Frank Howard in The Spirit of the Plays of Shakespeare (London, 1833)

Immediately before Lear’s entrance, Gloucester indicates his title (“The King is coming” [1.1.32]) and Lear is able to do what kings do, giving him an order he will execute (33–34), then dividing his kingdom (35–48). He sets the terms of the famous love contest, all the while complaining of just the accommodation he will soon miss:

Tell me, my daughters—

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state—

Which of you shall we say doth love us most,

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge. (48–53)

Rule is one of the habiliments of which Lear divests himself, only to miss it once he does. Before act 1 is over, Lear will be frustrated that he can no longer give orders and expect them to be carried out. By then, it is too late, since he has banished Kent, his faithful counselor (1.1.122–88), and disowned Cordelia, his good daughter (109–21 and 264–67), all the while turning over his kingdom and his care to Goneril and Regan, his evil daughters, and their lords (128–39).

Lear quickly loses the followers he had, as the Fool notes in his exchange with Kent, now in disguise as Caius to serve Lear and in the stocks for rowdy loyalty to Lear (2.2.252–70). The Fool teaches Kent what Lear should have known: most followers will abandon the powerful once they lose their power. By the time Lear is on the heath, he will have only two followers (Kent and the Fool) and one covert assistant (Gloucester).

Without more than a nominal title and few allies, he must depend upon his daughters. As he says of Cordelia before disowning her, “I … thought to set my rest / On her kind nursery” (1.1.123–24)—but, of course, having been flattered by her elder sisters’ courtly hyperbole of idolatry (see 1.1.54–61 and 69–76) and offended by Cordelia’s plain rhetoric of genuine love (95–104), he sends his youngest daughter to France and is beholden to the elder sisters, who no longer have any reason to flatter or care for him. The harsh justice of Goneril and Regan negotiating Lear down from one hundred knights to none replays his own tragic error of treating love as measurable, now played as the threatening chastisement and impoverishment of the elderly: as Regan puts it, “I pray you, father, being weak, seem so” (2.2.390). This cruel sport triggers his meditation on the accommodation he will shortly miss once she asks him why he needs even one follower:

O, reason not the need! Our basest beggars

Are in the poorest thing superfluous;

Allow not nature more than nature needs,

Man’s life is cheap as beast’s. (453–56)

Rather than be humiliated thus, he leaves their protective care to hazard the elements, already fearful of his sanity: “O fool, I shall go mad” (475).

When we next see him, he is raging against the natural elements of the storm:

I tax not you, you elements, with unkindness.

I never gave you kingdom, called you children;

You owe me no subscription. Why then, let fall

Your horrible pleasure. Here I stand your slave,

A poor, inform, weak and despised old man. (3.2.16–20)

He now has no protection from the storm, no food, and soon will disrobe himself to join Poor Tom in his unaccommodated state.

We must remember that Matthew’s first beatitude includes the material poverty Luke celebrates, but deepens it into spiritual poverty. Lear becomes materially poor through his own imprudence, his followers’ disloyalty, his two daughters’ abuse, his own mental decline, and the natural world’s severity, but he becomes spiritually poor through the Fool’s instruction and his encounter with Poor Tom.

We cannot look at all of the Fool’s exchanges with Lear, but he is clearly instructing him throughout 1.4:

FOOL. Can you make no use of nothing, nuncle?

LEAR. Why no, boy; nothing can be made out of nothing.

FOOL, to Kent. Prithee tell him, so much the rent of his land comes to; he will not believe a fool. (128–32)

“Nothing” is a resonant term in the play, as is so often observed; it is a not inadequate synonym for “poverty.” The exchange in the scene represents the Fool’s rough instruction of Lear. The fool teaches the wise, or at least powerful, man that he’s a fool:

LEAR. Dost thou call me fool, boy?

FOOL. All thy other titles thou has given away; that thou was born with.

KENT. This is not altogether fool, my lord. (141–44)

Kent, his political counselor (in disguise as Caius since his own exiling by Lear), and the Fool, his serious jester, both instruct him here in his folly. In the very next scene, Lear acknowledges that folly: “I did her wrong.” And in a touching but pointed rebuke, the Fool forces Lear to see the path of pathei mathos behind and ahead: “Thou shouldst not have been old till thou hadst been wise” (1.5.40–41). To which Lear immediately discloses that he is afraid of losing his mind: “O let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven! I would not be mad. Keep me in temper, I would not be mad” (43–45). Madness too perhaps is a poverty of spirit, the loss of the accommodation of reason, here the practical reason of temperance. The Fool’s particular form of friendship is to work on Lear’s behalf toward the human good of a recognition of responsibility for the error that has led to irrevocable reversal, leading him into the poverty of spirit in which his insight blends into madness, and his madness into insight, during the “tempest in [his] mind” (3.4.12). In this state, during his exchange with Poor Tom (again, Edgar disguised as a pauper), who has had his own experience of spiritual poverty,16 Lear recognizes (now that he shares it) the material poverty of some of his subjects:

Poor naked wretches, wheresoe’er you are,

That bide the pelting of this pitiless storm,

How shall your houseless heads and unfed sides,

Your looped and windowed raggedness, defend you

From seasons such as these? O, I have ta’en

Too little care of this. Take physic, pomp,

Expose thyself to feel what wretches feel,

That thou mayest shake the superflux to them

And show the heavens more just. (28–36)

Poverty of spirit is leading to the desire for justice, the fourth beatitude, and we see confirmation that the first beatitude can be the parent of the others. But I would focus on how that spiritual poverty is teaching him to love—first Kent and the Fool, then Cordelia.17

Immediately before Lear’s disquisition on the injustice of economic inequality, there is an apparently small moment I do not think small at all. Earlier, Lear noticed the Fool is cold: “Come on, my boy. How dost my boy? Art cold? / I am cold myself” (3. 2. 69–70). And when Lear and his ragged crew enter the hovel for accommodation, all defer to Lear as king to enter first, but he defers to them: first to Kent after he invites him to enter (“Prithee go in thyself, seek thine own ease” [3. 4. 23]), then to the Fool (“In boy, go first” [25]). This moment is easy to miss, but it is my evidence that Lear’s poverty of spirit is blessed, because it is animating an experience and act of love, of a desire for the good of another over and against one’s own. This subtle gesture is enacting a principle of the eschatological promise of the Christian ethic announced in Matthew: “So the last shal be first, and the first last: for many are called, but fewe chosen” (20.16). That is an instance of antimetabole, the rhetorical scheme of a repeated pair in inverse order:

I doubt I am the first to note this allusion, but I am convinced the argument and figure are just underneath Lear’s gentle command to the Fool: “go first.” One might accuse me of making too much of this moment, but I would say that the Lear we see in 1.1 would have been incapable of that small courtesy, and that virtue arises in small as well as grand acts—indeed, that the grand acts arise from the small ones. From this moment on, Lear shows a marked responsiveness to the presence and expectations of others.

Nowhere is that responsiveness more moving than in his reunion with Cordelia, who has invaded England from France to restore her father. Leaving aside her generous and loving treatment of him, so refreshing after Goneril and Regan’s cruelty, and leaving aside Lear’s fragile mental state, one notes that the scene shows his love for Cordelia, his humiliation having taught him the humility to submit himself to her judgment and ask for forgiveness:

LEAR. I am mightily abused. I should e’en die with pity

To see another thus. I know not what to say… .

CORDELIA, kneels. O look upon me, sir, and hold your hands in benediction o’er

me!(Restrains him as he tries to kneel.) No, sir, you must not kneel.

LEAR. Pray, do not mock me. I am a very foolish, fond old man. (4.7.53–54; 57–60)

During the reunion, Lear experiences love in the mutual submission of daughter to father, father to daughter: “You must bear with me. Pray you now, forget and forgive; I am old and foolish” (83–84). In both 3.4 and 4.7, we see a Lear who, because he is poor in spirit, can and does love.

And from this love, he is momentarily blessed with the earthly kingdom. That kingdom is troubling since it attends real suffering, so calling it blessed is difficult. As Cordelia says, “We are not the first / Who with best meaning have incurred the worst” (5.3.3–4). Remember that meaning best (in the virtues listed in the beatitudes) brings (in this world) the worst—for example, persecution in the eighth beatitude. The reunion of Lear and Cordelia is followed by their capture by enemies, and Edmund sends them away to prison.18 In giving us Lear’s beautiful and moving vision of the kingdom of heaven, participated in to a degree on earth, and hence a potential romance of suffering, Shakespeare not only answers the longing he knows his audience has for a happy ending—giving us a re-reversal from tragedy—but also represents how the earthly suffering of virtue might itself be blessed:

Come, let’s away to prison;

We two alone will sing like birds i’the cage.

When thou dost ask me blessing I’ll kneel down

And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live

And pray, and sing, and tell old tales and laugh

At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues

Talk of court news; and we’ll talk with them too—

Who loses and who wins, who’s in, who’s out—

And take upon’s the mystery of things

As if we were God’s spies. And we’ll wear out

In a walled prison packs and sects of great ones

That ebb and flow by the moon. (8–19)

Lear imagines a blessed existence in which one’s poverty and persecution allow one a space for playacting (including replaying the earlier scene of mutual forgiveness), prayer, song, storytelling, and political gossip, all figured as an understanding of mystery “as if [they] were God’s spies” on earth.19 The speech offers a representation of imprisoned blessedness in the human order.

Yet it does not last long, and Edmund’s interruption of Lear (“Take them away” [19]) is harsh, as seen in the metrics of the line shared by Lear and Edmund (“That ebb / and flow / by the moon. / Take them / away”), a harshness, even violence, made sonic through the metrical substitution of a trochee (“Take them”) for an iamb in the fourth foot of the otherwise iambic line.20 (Shakespeare is especially fond of trochaic metrical substitutions for reversals of action.) Lear’s response to Edmund catches the paradoxical character of the earthly kingdom: “Upon such sacrifices, my Cordelia, / The gods themselves throw incense” (20–21). Is the combination of loss and gain in their new life together blessed?

I ask, of course, because Cordelia is murdered. Lear’s bearing her lifeless body onto the stage is a famously disturbing figure for the pathos of tragic pathei mathos. In the terms of my reading, Lear’s loss of Cordelia exposes the paradoxical character of the earthly kingdom:

Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones!

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack: she’s gone forever.

I know when one is dead and when one lives;

She’s dead as earth. (5.3.255–59, emphasis added)

“She’s gone forever”: the heaven that is his in the earthly kingdom is cracked apart, and Kent’s response indicates what is at stake here: “Is this the promised end?” (261).21 In Lear’s re-re-reversal here, he could not be more impoverished, and his mourning is absolute. How on earth do we call the moment blessed? The offense to human experience in doing so would require an austerity toward human things that would be inhuman, but Shakespeare is the most human of poets. Perhaps Shakespeare is simply refuting the idea of the earthly kingdom, given its cost. Yet the cost is only apparent to Lear himself because of the love that poverty of spirit taught him; after all, when he disowned Cordelia in 1.1, his dismissal was attended by a desire for her nonexistence: “Go to, go to, better thou / Hadst not been born than not to have pleased me better” (235–36). Without the Fool’s instruction during his descent and the reunion with her afterward, arguably, he would have remained in such a state of hatred against her. It is not fortunate that she died, but it is fortunate that he loved her before she did. Just do not call him blessed on earth.

If not on earth, then in heaven, perhaps. Does the play offer the consolation of the heavenly kingdom? Here, Shakespeare is even more brutal to contented faith since he more than once holds out the possibility of a romance resurrection, only to deny it.22 With respect to my case about the beatitude’s place in the play, the anticipatory character of the heavenly kingdom is arguably delusional. Lear’s final lines upon Cordelia’s dead body certainly seem to shatter earthly blessedness:

No, no, no life!

Why should a dog, a horse, a rat have life

And thou no breath at all? O thou’lt come no more,

Never, never, never, never, never.

Pray you undo this button. Thank you, sir.

O, o, o, o. (5.3.304–8)

That wholly trochaic reversal of iambic rhythm (“Never, / never, / never, / never, / never”) catches at least the complete peripeteia of losing one’s child through one’s own error, but it may enact the materialist belief that, after death, we are nothing other than increasingly faint heat in a godless cosmos. Lear’s final lines follow and then hold out, famously, either delusion or hope in the play’s final vision:

Do you see this? Look on her: look, her lips,

Look there, look there! He dies. (309–10)

This vision is irreducibly ambiguous. Whatever “this” is and wherever “there” is, we simply have no way of knowing what Lear sees: Is it a materialist delusion or a beatific vision? I do not need to answer that question, fortunately, to prove that the play, once informed by the beatitude, is interrogating it. No human being would say that Lear is blessed on earth in the death of Cordelia, and no one knows, except through faith, if he is blessed elsewhere. Shakespeare’s romances represent paradisial moments after extreme suffering and death, but King Lear represents extreme suffering and death after a paradisial moment.

What, then, of love? If the ultimate blessedness of the kingdom of heaven for the poor in spirit is a fiction, does that mean the love responsible for that blessedness is also a fiction? Paul would think so, for, as he argues in I Corinthians,

For if the dead be not raised, then is Christ not raised. And if Christ is not raised, your faith is vaine: ye are yet in your sinnes. And so they which are a sleepe in Christ are perished. If in this life onely wee haue hope in Christ, we are of all men the most miserable. (16–19)

Faith, hope, and (one presumes) love are vain without the eternal horizon of reward, according to Paul. What difference does Lear’s courtesy to Kent, the Fool, and Cordelia make if we will all sleep forever in an exclusively material universe?

The Christian response to that question is to defend love as an imitation of God in a world that is not limited to its materiality. That, of course, is the argument of irrefutable faith, which means it is not an argument. The secular response may only be the trace of a faith no longer had, unless one finds Richard Rorty’s defense of “solidarity” in the shared fear of violence compelling.23 The scandal of the Christian order is that it does not love when it knows it should; the scandal of the secular order is that it loves when it does not know why it should. Shakespeare wrote, and his theater company performed, King Lear in the early modern period when, to simplify the history of modernity, one might note that the Christian order was dying and the secular one being born. I certainly cannot resolve the tension exposed here. All I can say is that, in the moment on the heath when Lear loves the Fool (“In boy, go first”), it is the right thing to do. That may be the reflex of an ethical Christianity without metaphysical foundation; that may be a human solidarity found in the human bond alone. I do not know. I know only that the scene is my touchstone: in the storm, notice another is cold and let them enter first. That is the wisdom into which we may suffer in a time of plague while under the influence of the beatitudes, King Lear, and the conversation between them.24

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy