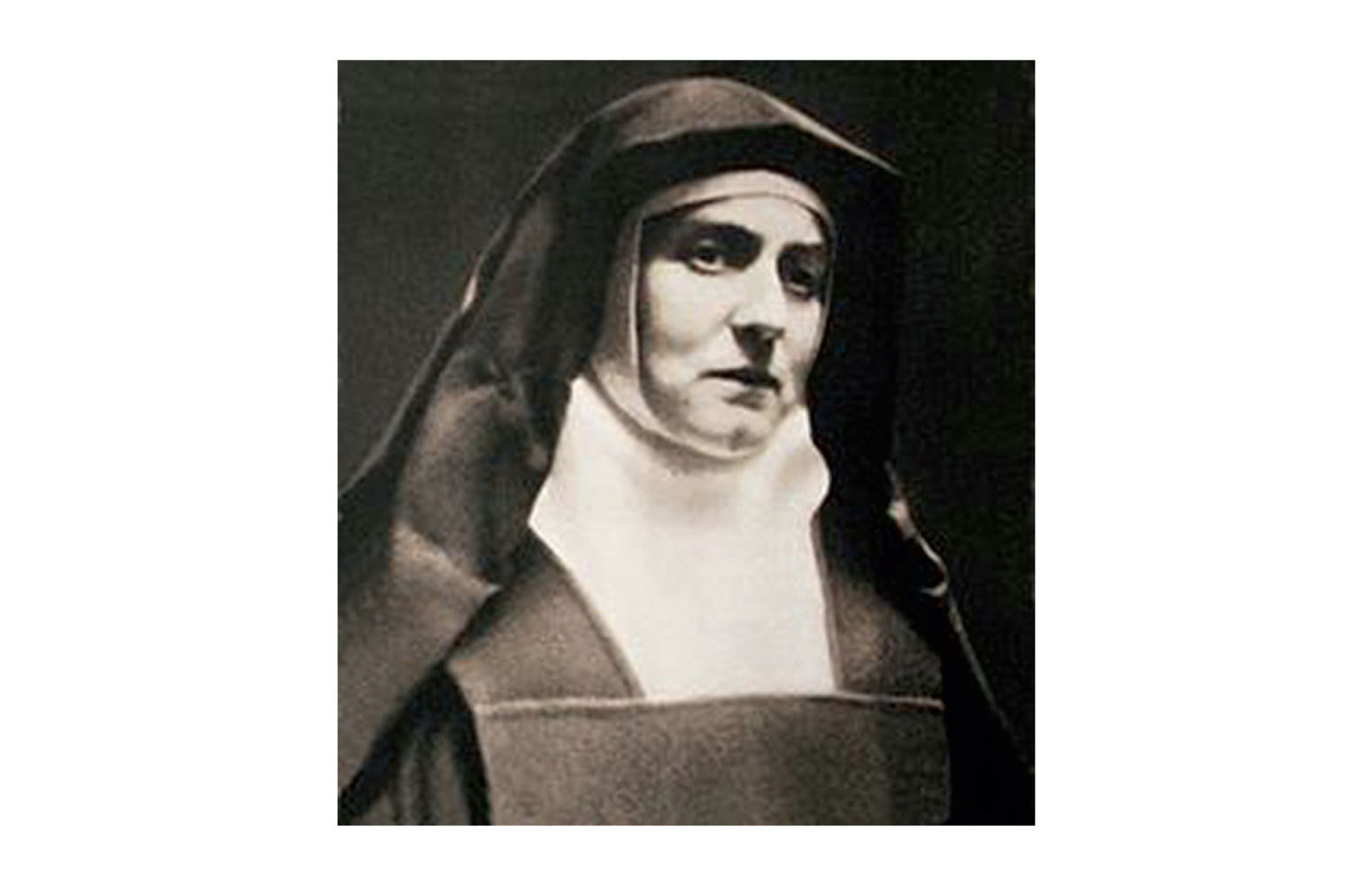

Edith Stein, a German Jewish convert to Roman Catholicism, became a nun of the Carmelite order and was executed by the Nazi government.

[Knowledge in general]

Knowledge is the mental [geistig] grasping [Erfassen] of an object. In the strictly literal sense it means grasping something that has not been grasped before. In an extended sense it includes an original [ursprünglich] possessing without beginning and a having-in-possession that goes back to a grasping. All knowledge is the act of a person.

Knowledge as newly grasping can in turn be taken in a broader and narrower sense. It has the broader sense when the perception [Wahrnehmung] stands for sense knowledge and the narrower sense when the object of the knowledge is said to be states of affairs or knowledge is said to appear first in judgment. In the latter case it denotes the insight [Einsicht] that something is, or that something is thus, or that something is this. States of affairs can be known on the basis of an intuitive [anschaulich] grasp of objects or on the basis of other known states of affairs. But in the end any knowledge of affairs harks back to an intuitive grasping of objects. Intuitive grasping can be sense perception or intellectual viewing [schauen].

[Objects of knowledge]

In all knowledge the object is given as a be-ing [Seiendes]. To the various kinds of knowledge acts there correspond different objects, different ways in which the objects are given and different ways in which the objects are. Things, their properties, processes, are objects of sense perception. Their way of being given is their appearing to the sense, and their way of being is their existing in space and time.

Intellectual viewing may be the grasping of persons having minds, of their acts and properties, or of objective [objektiv] individual structures of mind, or it may be the grasping of ideal objects. The way that individuals possessing a mind and their accidents are given {50} is the understandable expression. A person’s way of being is being-there-for-itself [Für-sich-selbst-dasein] and being-open-for-what-is-other [Für-anderes-geöffnet-sein]. The way of being of objective individual structures of mind is being-there-through-persons and being-there-for-persons. The way of being of the ideal is being in (a concrete individual), really [wirklich] or possibly.

Being cannot be defined for it is presupposed by any definition since it is contained in every word and in every meaning of a word. It is grasped along with anything that is grasped and it is contained in the grasping itself. We can but state the differences of being and of be-ings.

[Divine and finite knowledge]

The knowing person is a be-ing. The act of knowledge is a be-ing, what is known is a be-ing. When the knowing person knows himself, the knower and what is known are the same be-ing. Only in the case of Pure Act can we say this of a knowledge act and of what is known. In any finite temporal act the knowledge act and what is known are distinct, even when the knowledge act is what is known and when it is known in a reflection, which is the awareness accompanying the act and coinciding with it in time. Hence we must say that every finite act of knowledge transcends itself.

Pure Act, which is Absolute Being and which is everything that is an outside of which there is neither being nor be-ings, cannot transcend itself. Everything that is, is in it and is known in it. Hence no be-ing can be unknowable (or more precisely, unknown). If we call {51} a be-ing “intelligible” insofar as it is known … and render “intelligible” as “thought [Gedanke],” we may then call all be-ings “thoughts.” But it still does not follow from this that every be-ing must be knowable for finite minds, nor that we may speak of “thought” in the same sense in the case of God and finite minds.

A be-ing’s knowability and its being known have meaning only in reference to a knowing mind that does not possess knowledge originally but must gain it step by step. It is not obvious to our insight [einsehen] that every be-ing must be knowable to such a mind. It is immediately obvious only that no one can make statements [Aussage] about a be-ing of which he knows nothing. So if I say “there may be a be-ing that I cannot know,” the words are meaningful only if I know something about it, to be precise, enough so that it is obvious to my insight that there is a gap in this knowledge and that it cannot be filled in with my own means of knowing. For a mind able to conceive a formal notion [Idee] of being—the need for the notion to be materially filled in the various modes of being and the mind’s inability to take stock of the possible fillings in—“being” signifies more than can enter into its knowledge. So for such a mind the equation being = being-knowable does not hold (as long as the knowledge is supposed to cover the be-ing completely). But it is not obvious to our insight that there must be some finite mind for which every be-ing would be fully knowable. Therefore only the equation being = being-known-by-God holds, but not being = being-knowable (fully).

[Accessibility to a mind]

This poses two questions: (1) Must some be-ing be accessible to every finite mind? (2) Under what conditions is a be-ing accessible to a finite mind?

Ad 1 [reply to the first question]. The being of persons having minds is essentially living aware of self and directed to objects. So there can be no mind to which no be-ing would be accessible, that is, to which nothing would be knowable. Self-awareness (in the sense of reflection) and acts directed to objects are distinct types of knowledge. But the mind itself can also be the object of an act of knowledge.