Dec 19, 2018

Language Is Not Mechanical (and Neither Are You)

College of the Holy Cross

Caner K. Dagli is an associate professor of religious studies at College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

More About this Author

College of the Holy Cross

Caner K. Dagli is an associate professor of religious studies at College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts.

More About this Author

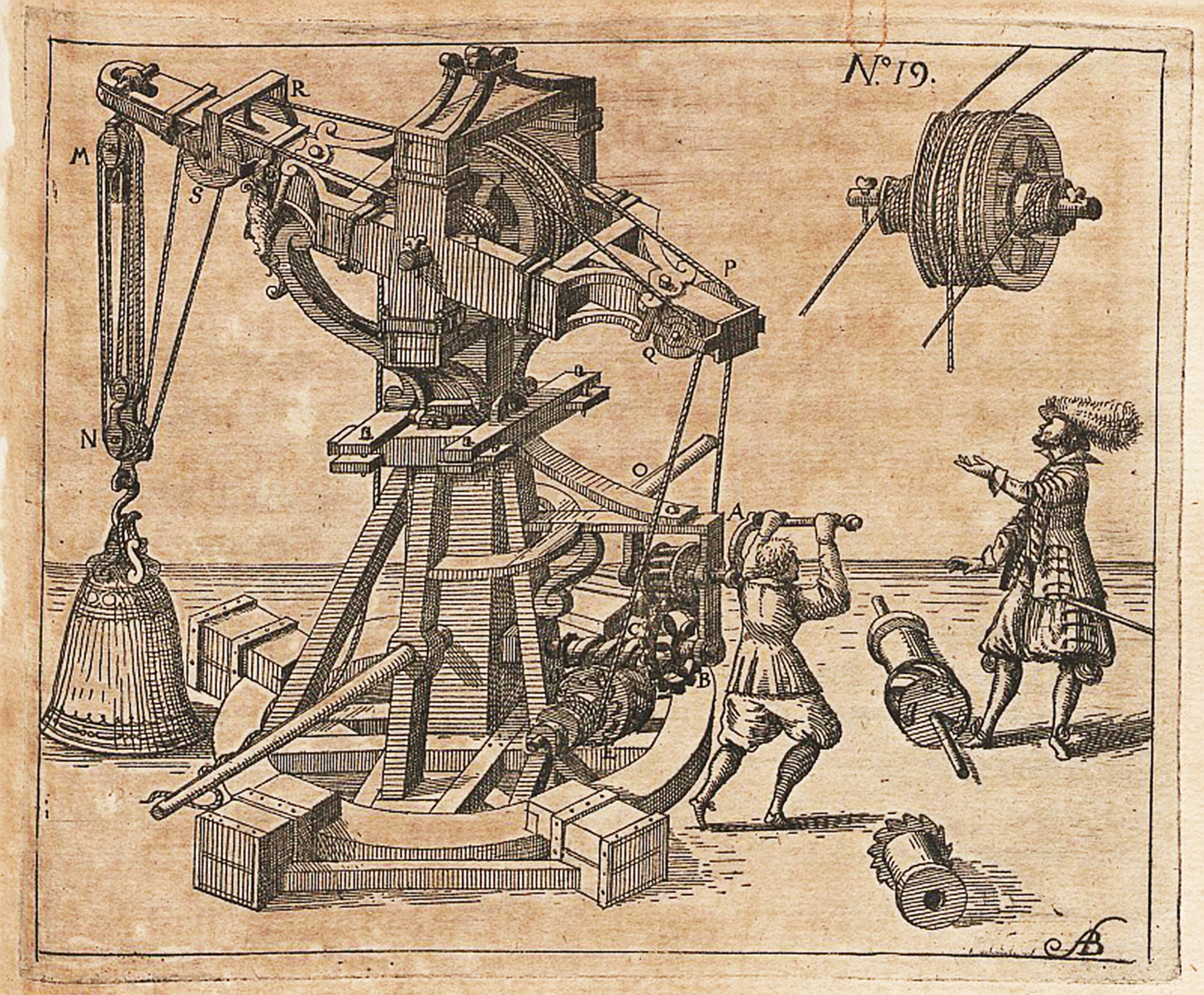

The world is reduced to physical components in mechanical philosophy. Illustration: Hieronymus Megiser, 1613

Once upon a time, to explore ultimate questions meant finding out about being. One might start with “What is it to be a human being?” but eventually end up at “What is it to be at all?” In traditional Islamic, Christian, and Jewish thought, the ultimate aim was to understand the relationship between Being and beings, or between God and things. The cosmos was conceived of as a hierarchy of beings, meaning that not only were there different beings (your soul, your body, your pet, your chair) but different levels of being (rational, animal, vegetable, mineral). Human beings knew things because humans and things were in the same realm of being, and knowledge was a real relationship between one being and another. However the details of this relationship were described by different thinkers, there was an assumption that the knowing faculty of a human being is actually connected with the known object.

The first modern thinkers abandoned the traditional explorations of being and instead reframed ultimate questions in light of a new vision that divided the world into two distinct substances: mind and matter. Starting in the seventeenth century, figures such as Descartes, Galileo, and Newton left God and the human mind intact as immaterial entities, but they conceived of the rest of the cosmos (including our own bodies) as mere matter in motion. This material world was conceived not as a hierarchy of beings but rather as an aggregation of (literally) machines all made of the same stuff, designed and built by God. The new “mechanical philosophy,” as it came to be called, conceived of these machines (including all plants and animals) as resembling the devices constructed by the artisans of the day, with their levers, pumps, screws, wedges, gears, and wheels.

Finding out the nature of things thus became a matter not of understanding what kind of beings they were but of working out the details of how the great cosmic device worked. The larger, and unsettled, question was “How does our human mind, which is utterly immaterial, know the world, which is utterly material?” Against this metaphysical backdrop, instead of asking, “What is a human being?” and following that trail to bigger questions (e.g., “What is being?”), thinkers were led down a different path, to questions such as “How do we even know that the object before me is actually there?” The ultimate philosophical prize was no longer the correct articulation of first principles of being but the defeat of the skeptic. Philosophers were compelled to replace being with knowing as their central concern.

According to the new mechanical philosophy, one may think that one is experiencing a fragrant red rose, but that experience of smell and color is inside the mind. The rose itself is neither fragrant nor red but is a machine whose motions somehow (it is unclear how) correspond to the immaterial experience of fragrance and color. You may think that your awareness of the rose as a rose is your knowledge of the rose, but it really is not. What could connect a knowing mind with the material object if the former is completely immaterial and the latter purely material? A mind is locked out of the machine-world of animals, plants, and minerals. The most one can say is something like “The rose is red as long as we define red in terms of the machine-like attributes that rose actually possesses.” Otherwise one is simply saying, “I’m having a reddish fragrant experience.” The bifurcation of the world into mind and matter led many thinkers to abandon the notion that we can have knowledge of things as they are and to accept that we can only have knowledge that things are the way they are.

“Relating immaterial minds to material machines was a real puzzle, but if there are no such minds, then there is no puzzle.”

This epistemological shift raises a host of questions, but it relates to language in the following way: the difference between “knowledge of the red rose” and “knowledge that the rose is red” is that the latter is always a kind of proposition (i.e., a statement of the form “x is y”) and, more specifically, something that can be characterized as either true or false. When “knowledge of” disappears from our discourse and all knowledge becomes “knowledge that,” then all knowledge becomes, in principle, expressible as a sentence (a subject-predicate) in some kind of language. If all knowledge is expressible, then knowledge and language have a one-to-one correspondence with each other even if they are not identical with each other; for example, my awareness of the rose’s redness is expressible as “the rose is red” even if that redness I perceive is not actually in that thing in the external world (i.e., external to my mind).

It is crucial to keep in mind, however, that in this “substance dualism” it was still possible to distinguish between thought and language: one could think something and then express it. Thinkers such as Descartes recognized that there was something creative and free in human language that allowed human beings to utter new sentences and meanings in virtually limitless varieties, and this capacity could not be attributed to any mechanical process; hence the realm of the mind had to be separate from the material machine. The mind might no longer have been capable of direct knowledge of the world but the immaterial mind could have a kind of knowledge about the world, and could think and speak freely about the truth or falsity of propositions such as “snow is white” or “the cat is on the mat,” since the mind was not material and therefore not bound by the laws of the cosmic machine.

By the nineteenth century, substance dualism waned, as minds themselves came to be understood as aspects of the material machine, a view that was cemented at the center of modern thought by Darwin’s evolutionary hypothesis. Darwin claimed to account for all human traits—of body and of mind—on the basis of material processes. With Darwinism, substance dualism was replaced by a kind of monism in which all reality was just one substance: material, natural, and physical. The question of how an immaterial mind can know what is happening in the material world of bodies—a question that has been at the heart of modern philosophy for a long time—ceased to be a meaningful pursuit (though it reappeared as the so-called hard problem of consciousness). Relating immaterial minds to material machines was a real puzzle, but if there are no such minds, then there is no puzzle.

Darwin was certainly not the first person to think of our cognitive capacities as being purely physical, but he did cast that vision into a form that has crystallized as common sense in many quarters. According to this view, our thoughts, feelings, sense of belonging, and love (despite our experience of them as something else) are constituted by material processes that evolved through some combination of determinism and/or randomness. What we call the “mental” is just one pattern among the many patterns of the material. The Darwinian picture of human beings allowed almost every aspect of human consciousness to be reframed in terms of brute material processes. The most seemingly immaterial realities—a deep love, a transcendent beauty, a sense of purpose, an act of courage—could all have a story conjured for them in which, in some distant past, an ancestor acquired a beneficial mutation that was reproduced over time.

Yet we do not have a clue about how Darwinian evolution could account for human language, any more than Descartes could account for it in terms of mechanical processes. Traditional monotheistic theology taught that the feature that distinguished human beings from animals was their rational soul (unlike the soul human beings shared with other animals) and that there was an intimate connection between this unique faculty and the ability to use language. Indeed, Islamic thinkers defined human beings as ĥayawān nāţiq, usually translated as “rational animal,” but which could also be rendered as “animal capable of speech.” Then, after Descartes, philosophers (whom we would call scientists) used to say that animals were just machines, that our human bodies were machines too, and what distinguished human beings from animals was the presence of the immaterial mind, which was responsible for the ability to speak human language. After Darwin, we are seen as just accidental patterns of molecules, and yet, even now, what continues to distinguish us from the animals is human language.

When it comes to those aspects of consciousness we seem to share with animals, there is a certain plausibility to explaining them as material processes, since even thinkers before Darwin believed animals were quite literally soulless machines. But language, with its richness, freedom, and infinite possibilities, remains essentially unexplainable in terms of material processes—despite considerable effort for over a century. With mind-matter dualism, we believed that thought, originating in an immaterial mind, could be expressed through language but was nevertheless not reducible to it (since an immaterial mind was doing the thinking). But then what is language (and what is thought?) when immaterial minds disappear and leave only material stuff? The loss of the immaterial mind and the persistence of the enigma of language displaced knowledge as the central concern of philosophy, and language took center stage.

Charles Darwin

Put another way, in the levels-of-being view that prevailed before modernity, philosophers would ask about some object, “What is x?” and answer, “x is y,” but the ultimate question to be answered was “What is it to be at all?” With the advent of substance dualism, the central subject of philosophy became “How does one know that ‘x is y’?” Finally, after the puzzle of knowledge was lost with the loss of the immaterial mind, philosophers came to focus on the question of “What does it mean to say, ‘x is y’?”

It is thus not a surprise that no topic in philosophy has received as much attention in the last century as language has, so much so that many came to speak of a “linguistic turn.”

Modern philosophers, whether analytic or continental, whether consciously or not, remain constrained by the claim that human beings are nothing but biomechanical machines, and all that is human must therefore be explicable in those terms. Whatever is said about language must not violate the post-Darwinian notion of human beings as complex material machines whose structures and functions are the result of deterministic or random processes that can only be correctly described in biology, chemistry, and physics. Nevertheless, academic philosophers have not figured out how to frame the phenomenon of language in terms of the deterministic and/or random metaphysics that forms the background for modern claims about what human beings are.

Most importantly, there is an implicit or explicit identification of language with thought; crucially, there is also an assumption that there is no thought before language. Rather, what we call thought is really just another kind of language. There is no prelinguistic entity that then enters into linguistic form. It is “language all the way down.”

In the analytic movement of academic philosophy, Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein first proffered their idea of “logical atomism,” which Scott Soames described as “an utterly fantastic metaphysics and a completely unrealistic conception of an ideal, logically perfect language, somehow underlying our ordinary thought and talk,” a language that could, because of the assumed metaphysical correspondence between language and world, “adequately capture all truths.” Later, this view was abandoned (by Wittgenstein himself ), and analytic philosophers moved on to a so-called ordinary language philosophy, which taught that by attending to the use of language, we would come to realize that philosophical problems are really just linguistic problems (i.e., confusions about how we use language). The ideal language philosophers and the ordinary language philosophers, despite their differences, were all driven by a thoroughgoing scientism neither willing nor able to question the status of material monism as the absolute truth about human beings. For the ideal language philosophers, discovering the logically perfect language underlying all ordinary talk would reveal both the real nature of language and also the nature of the world, while for the ordinary language philosophers, any metaphysical talk about the world was a non-ordinary use of language that needed to be dissolved since, as Wittgenstein remarked, “nothing is hidden.” Within this philosophy of language (and linguistic philosophy, a difference not germane here), there was an uncompromising faith in Darwinian metaphysics, and the assumption that all human behavior could be explained in terms of the actions and interactions of molecules hardly needed to be stated, never mind defended.

The background assumption is that language has a causal history that we can view as a series of progressively more sophisticated physical interactions between physical objects. Take the example of the visual system: in the evolutionary framework, a group of photosensitive cells mutated gradually into a fully formed eye and visual system, a process of simple photosensitivity transforming stage by stage into highly complex photosensitivity (namely, our ability to see). It is similarly assumed that the human language system has its origin in some kind of gradual, complex interaction between things (akin to the increasingly complex relationship between light and special cells) that would eventually become, in human beings, the connection between words and things. The steps involved are totally speculative and the nature of this development unimaginable, but these shortcomings rarely seem to count against the theory.

On the continental side of the philosophy spectrum, the focus was on exploring language as a part of culture, an inescapable matrix outside of which no thought is possible. “Language is the house of being,” said Heidegger, and also, “Only where there is language is there world,” and worst of all, “Language speaks.” Gadamer said, “Being that can be understood is language.” The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan (an inspiration for contemporary philosopher Slavoj Zizek) said, “Psychoanalysis should be the science of language inhabited by the subject,” and that “the unconscious is structured like a language.” Language is never an instrument or an expression of thought but instead produces it, or is at least coterminous with it.

One defining feature of human language that makes it so difficult to explain in material terms is its ambiguity—the fact that one can use the same expression to mean different things and still be understood. It is difficult to find a human sentence that could not be understood in multiple ways; how then, do we get it right? How do I say what I mean, and how do you interpret my words to understand the meaning behind them?

As a rule, philosophers in the analytic tradition have been unwilling to part with truth and meaning (although they turn these words into technical terms far removed from their commonplace use); for them, the ambiguity and freedom of language could be overcome if the correct technique of thinking about language could be discovered, whether this means discovering the hidden ideal language (as in early Wittgenstein) or dissolving our confusions through the correct understanding of use, or some combination thereof (as in later Wittgenstein). Analytic philosophers tend to avoid linguistic determinism—the notion that our linguistic inheritance determines what we can think. They seem to believe that they are free to use the language and concepts they use, and that human beings are able, when it comes to truth and meaning, to get it right even though these philosophers’ account of human nature (deterministic and/or random) does not allow for any such freedom to be real.

One defining feature of human language that makes it so difficult to explain in material terms is its ambiguity—the fact that one can use the same expression to mean different things and still be understood.

Philosophers in the continental tradition, the other main wing of modern academic philosophy, have tended to find the ambiguity and freedom of language to be an insuperable obstacle and have, by and large, surrendered to this ambiguity. Instead of searching for a “theory of truth” or “theory of meaning,” they set about (à la Heidegger) finding various coping strategies in order to allow people to become authentic within the inescapable constraints of language. Continental philosophers tend to explicitly reject the kind of freedom in language that analytic philosophers seem to take for granted: we are not really free in our use of language, they say, and we cannot really get at the meaning of words because there is no such meaning. Language is not something in us (as thinking beings), rather it is we who are in language. Continental philosophy has neither attempted to escape nor succeeded in escaping from this self-imposed prison, in which human beings are at the mercy of the system of symbols they use, because meaning is never fully determinate—or because meaning is always a function of power or because “there is nothing outside-of-the-text/no-outside-text,” and the like.

It is astounding, one should note, that luminaries in both the analytic and continental wings of the modern philosophical tradition often portray themselves as having newly discovered the problems of ambiguity in language, as if no thinker before the twentieth century had noticed that words can be ambiguous in very subtle and consequential ways; that they change meaning depending on context, speaker, and audience; that they mean something different when spoken in isolation compared with being spoken in the presence of near synonyms; that any number of logical fallacies and abuses can arise from slightly inconsistent uses of the same word; that metaphysical presuppositions are built into certain concepts; and so on. These are old concerns, and no one deeply familiar with the tradition of, for example, Qur’anic commentary and classical Arabic grammar would be the least bit unfamiliar with them.

What is in fact new to modern philosophy, however, is the effort to restate these insights about language so they ring true within a Darwinian metaphysics, thereby avoiding the dreaded dualism of a nonmaterial soul or mind that actually is free and conscious and uses language from the outside of language. The novelty of modern philosophy about language is not any insight into the richness and ambiguity of language per se, but the effort to account for this richness and creativity without violating the Darwinian imperative to reduce all human behavior to evolutionary determinism or randomness.

So how is language viewed outside the world of academic philosophy? The field of linguistics offers an instructive contrast to both analytic and continental philosophy when it comes to language, a fact that is surprising at first, considering how many foundational assumptions they share. Both sides seem to operate under the presupposition that modern science is the only way to learn anything true about the nature of reality. They also agree that human beings acquired language through some evolutionary event and that our only hope of understanding language resides in modern science.

The most important figure in this regard has been the linguist Noam Chomsky, whose work in language was so influential that it had to be taken into consideration by academic philosophers, even though only a small minority of philosophers subscribe to Chomsky’s views on language. Chomsky is not a member of the philosophy establishment, but because of the central role of language in twentieth-century philosophy and the impact and reach of Chomsky’s views, he has been treated as an important voice within academic philosophy.

Chomsky argues that language should be studied like any other human system, such as digestion or vision, and that there is nothing decisive in our intuitions about language that would make it something we should study in a different way. But, he argues, many philosophers are guilty of this “methodological dualism.” In other sciences (such as physics), “the critical analyst [i.e., philosopher] seeks to learn about the criteria for rationality and justification from the study of scientific success” no matter how inscrutable or paradoxical the findings are (e.g., in quantum mechanics). In the case of language and other cognitive capacities, however, a line is crossed, and “the critic applies independent criteria to sit in judgment over the theories advanced and the entities they postulate.” In other words, the philosophical critique of the sciences stays in its lane when it comes to the other sciences, but when it comes to the study of language, the rules change and philosophers seem to privilege their intuitions over the findings of the scientists (or just ignore the latter altogether).

What can account for these differences between academic philosophers and linguists, since both essentially accept that language is a feature of biological inheritance?

Noam Chomsky

Chomsky presupposes that there is much we do not understand about human consciousness, and crucially, much we may never understand, and perhaps we may lack the capacity to even ask the right questions. Why should human beings, in principle, be able to understand everything about human beings? For Chomsky, our cognitive capacities have a limit, and that limit also implies a scope. We ought to study human cognitive capacities, using the best methods available, but without an assumption that we will find all the answers. As a linguist, Chomsky believes we ought to study human language the same way we study human digestion or chemistry—beginning from commonsense notions but always prepared to discard them when some data or a superior theoretical framework becomes available. Scientists use terms such as optical, electrical, and chemical not to describe some kind of “metaphysical divide” between them but as informal designations in empirical inquiry. Chomsky uses language and linguistic the same way we use physical and chemical—not to make metaphysical demarcations but simply to make our way around.

Linguists like Chomsky, in the world of modern science, are comfortable in their commitment to methodological naturalism, without subscribing to a metaphysical naturalism that would imply we essentially know the basic parameters of reality and are simply filling in the blanks. For Chomsky, the horizons for understanding human cognitive capacities remain very far in the distance, even though some progress has been made. He maintains a commitment to the scientific study of language, while refusing to make evidence-free claims about how it evolved, how “the brain” produces it, and so forth, since in his view, even the best modern science we have still tells us almost nothing about such questions as free will, morality, or the nature of consciousness. He is willing to say we do not know much, and may never know much, but here’s the best way to explore it.

Many modern philosophers have not been able to bite this bullet; they refer to Chomsky and others as “the new mysterians,” and like orphans searching for a parental figure in their lives, they seem desperate to hold onto something resembling the immaterial essence they lost to the materialist worldview. There is a soul-shaped hole in their hearts, and they have filled it with “language,” as produced by their intuitions and speculations, rather than the science they claim to rely upon. The new mysterians, including Chomsky, are willing to simply accept that soul-shaped hole, but it would seem that philosophers of language have failed to cope fully with it. In a way, the philosophers talk about language the way philosophers (and theologians) once dealt with reason or intellect—namely, as a real entity whose nature could be known through introspection or intuition (or in the case of the theologian, combined with trust in an authoritative revelation). The philosophers deal with language and meaning as if these were as real as the mind was to Descartes, and they imbue them with many of the same properties he ascribed to the mind. A linguist like Chomsky sees this as an unjustified assumption: he does not believe modern science gives us any reason to believe that knowledge about the nature of human language is any more available to intuition and introspection than is knowledge about the nature of the digestive system.

Why is this position (which goes beyond questions of language) seen by some as mysterianism? Chomsky points out that a basic mystery of language is that human beings say things that are “appropriate to circumstances but not caused by them.” If our ability to speak (and, obviously, first to think) is “not caused by circumstances,” then what is it caused by? Is our speech caused at all? If language is in fact caused by circumstances, then it is meaningless to speak of it being “appropriate” to circumstances. If it is not caused by circumstances, then it perhaps is uncaused, which is far from satisfactory for a scientist or philosopher. Or perhaps it is caused, but by some separate set of circumstances different from the circumstances of speech, which would imply some sort of metaphysical dualism—a soul perhaps? This is also undesirable from the point of view of modern science and philosophy.

“Appropriate to” means that when we say something about reality, we can get it right or we can get it wrong. Without a real choice between possibilities—for example, “the sky is green” versus “the sky is blue”—human language is just noise. If it were inevitable that you would say “the sky is blue” because a deterministic cascade of causes and effects led to that sound emanating from your lips, then you would be neither right nor wrong. Rather, the words would be an arbitrary cross-section of all the noise happening in the universe at that moment. But wait, one may say, quantum mechanics tells us that physical reality has an intrinsically indeterministic aspect, so one need not believe in a clockwork determinism. But that objection simply substitutes randomness for determinism, and so rather than the statement “the sky is blue” being predetermined by circumstances, it is arbitrarily connected with them, like doing algebra with dice. That is to say, in the case of determinism, you have to say what you say, and in the case of randomness, you just happen to say it. But human language and thought are only meaningful when someone can actually mean them, and no one can mean something accidentally or deterministically.

What separates linguists such as Chomsky from the main run of academic philosophers is that they simply accept this difficulty (even mystery) in understanding freedom and ambiguity in language against a scientific backdrop. Chomsky assumes we may never understand language, and based on that, he takes a stand on the correct way to inquire into it systematically. Analytic philosophers have continued to search for a theory of meaning or a theory of truth, in the hope that such difficulties can be overcome—to rescue meaning from the jaws of materialism—while continental philosophers typically take a leap into the gaping maw of meaninglessness and embrace the notion that there is no truth, no meaning, no way to get it right.

“[In Chomsky’s view], even the best modern science we have still tells us almost nothing about such questions as free will, morality, or the nature of consciousness. He is willing to say we do not know much, and may never know much, but here’s the best way to explore it.”

Chomsky’s views on language highlight the difference between a methodological commitment to scientific investigation and a metaphysical commitment to a certain view of human nature. However, even if he rejects the overzealous naturalism of someone like Daniel Dennett and other “moist robot” theorists, Chomsky does not reject a more modest and self-aware naturalism. After all, stating that language should be approached as one would approach the digestive system presupposes a certain metaphysical view about what human beings are in the first place, however conservative and careful that view might be. These are not the only reasonable views available to us. We are not obligated to choose between minimalist and maximalist versions of metaphysical naturalism or between tentative and cocky versions of computationalism, functionalism, connectionism, and the like.

For many, hope seems to lie in the domain of computers and so-called computer languages, which dangle the promise of understanding how a system of matter in motion (e.g., the physical brain) could produce intelligence and rationality. Just as the first modern philosophers reimagined the human body in terms of the mechanical devices of their day, contemporary philosophers and scientists have recast human intelligence in terms of the dominant device of our day: the computer. The image of the human brain as a computer has become so pervasive and influential that it is almost not a metaphor anymore but rather is considered something like common sense. The notion of machines becoming sentient has captivated the popular imagination for generations (from 2001’s HAL to Star Trek’s Commander Data to the robots of HBO’s Westworld), because if it is possible for a machine built by us to have intelligence, this possibility can make our own intelligence finally comprehensible in light of Darwinian metaphysics. We lost the immaterial mind to modern materialism, but it may be possible to rescue consciousness from the grip of determinism or randomness if we are able to make our own material machines truly conscious. Then our inability to account for consciousness in light of the deterministic and/or random view would no longer be a failure but would constitute a mere delay in working out the circuitry and pathways of the brain and how its firings/connections (no one really knows what) create consciousness.

Big Data, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), 2013

Of course, it is an absurd dream. Computers can never do things that are appropriate to circumstances but not caused by them. What a computer does is always and only caused by circumstances: the hardware, the software, the inputs, and so forth. If you know what a computer is doing now, you know (in principle) what it will be doing next. A computer neither gets it right nor gets it wrong. A computer does not “follow” instructions because a computer cannot “disobey” instructions. One does not “tell a computer what to do” any more than winding a clock and adjusting its hands tells the clock to work. Computers have languages (e.g., Java, Python, and C++) in the way that tables have legs. In fact, they are not really languages at all but merely complex interfaces between human beings and their machine creations. These interfaces are deterministic and have zero room for ambiguity. The zeros always are zeros, and the ones are always ones. Even the notion that computers use zeros and ones is misleading because we human beings understand these numbers in light of all other numbers. For the machine, zero and one are simply off and on. The computer reads them the way a player piano or music box reads a sheet of holes or bumps.

Language is the linchpin by which we bridge the gap between machine and human being. We elevate the language of computers while reducing human consciousness to language and then language to material processes, in the hope they will one day meet in the middle.

That is, a computer language is just a complicated mechanism that lets a human being configure a machine (the computer) to do what he wants that machine to do. Consider the following analogy. When an organist wants a pipe organ to sound differently, he adjusts the stops of the pipes to change the air flow and produce a different sound (this is where we get the phrase “pulling out all the stops,” which is how the organist gets the biggest sound). Now, in fact, mechanisms exist by which one can quickly change multiple stops with a single gesture to give different acoustic profiles. In the olden days, one had to manually adjust the stops, but today one can press a button and a machine will do it for you. But by pressing the “clarinet” or “trombone” button on an organ, you are not telling the organ to sound like a clarinet; the organ is not “following instructions.” Rather, you’ve set up all the parameters first and have also set up efficient ways of shifting and adjusting multiple parameters at the same time. The pipes do not know that the button has “clarinet” written on it.

In this metaphor, the mechanism that opens and closes the stops is like software, the blowing air and pipes are the hardware, and the musician is the programmer. The sound is the output.

It is easy to imagine a thing “thinking” when its workings are hidden from you. Today, computing operations are incredibly fast and complex, and the machines that perform them are usually remote from our view, and thus the process takes on an air of mystery that somehow leaves us space to imagine that this is how the human mind works: billions of neurons or connections or firings or whatever is supposed to collectively constitute consciousness (no one knows) somehow produce thought and meaning.

It is instructive to go back to the time, not too long ago, when every operation of a computer was mechanical and one could truly see it work. A video from 1948, for example, shows a computer whose innards look like the innards of a clock. If it were built larger, people could even walk around inside it; and yet this collection of gears, rods, and levers does exactly the same thing as today’s supercomputers, the only differences being speed and volume. Give this computer long enough, and it could do the same tasks. In fact, give human beings with pencil and paper a set of instructions, and they could perform the same tasks and produce the same outputs, even if they understood nothing except what to write on the paper when given a simple input. How consciousness and intelligence arise from such intricate setups is left completely to one’s imagination, and the link between such operations and intelligence is simply proclaimed but never demonstrated.

But wait, someone might say: today’s algorithms are so complex that they seem to learn and do things we did not program them to do, things we cannot predict. Indeed, complex algorithms do unexpected things, and they seem to expand beyond what they were originally meant to do, so we imagine (vaguely and colorfully) that what computers are doing converges on what the human brain is doing. But the fact that a computer produces an unexpected output simply means we did not expect or could not predict it, not that the machine has started to think. Even extremely simple situations produce unpredictable outputs: the trajectory of three bodies in space cannot be solved exactly in mathematics (the famous “three body problem”), and the movements of a simple device called a double pendulum (a swinging arm with another swinging arm attached to its moving end) will quickly become chaotic and unpredictable once set in motion, even though it has only two moving parts. Unpredictability and/or randomness are not new problems, and their appearance in material systems is not an indicator of intelligence or learning.

So, while there is no danger of computers becoming intelligent, it might be the case that human beings will set up a machine that does something horribly destructive in ways we could not have predicted. But if we leave off such hypothetical scenarios, we can observe with certainty that human beings have already radically altered their conception of what constitutes intelligence so that the machines they create will fit the bill. As computer scientist Jaron Lanier has argued in his book You Are Not a Gadget, “The Turing test cuts both ways. You can’t tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you’ve just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart.” He uses the example of one of the most common interactions people have with a machine: “Did that search engine really know what you want, or are you playing along, lowering your standards to make it seem clever?”

In the case of computers, the question of intelligence hinges directly on the question of language. Language is the linchpin by which we bridge the gap between machine and human being. We elevate the language of computers (which is not a language at all but a mechanical interface), while reducing human consciousness to language and then language to material processes, in the hope they will one day meet in the middle. It is a kind of suicidal blasphemy, in which we degrade ourselves beyond recognition in order to win the power to create life. We first tried to mechanize the body, and failed. Now we are trying to mechanize consciousness.

None of this is necessary. It was not necessary to discard traditional metaphysics in favor of mechanical philosophy, not least because mechanical philosophy turned out to be wrong in every respect. Newton’s own theory of gravity had no mechanical aspect to it, much to his chagrin, and physics later reintroduced occult influences in the form of forces and eventually completely destroyed any intelligible notion of matter or mechanism with the advent of quantum mechanics and relativity. Nor was it necessary to reduce all things human, including consciousness, to a product of random and/or deterministic processes and then begin to speak of the mind as a computer.

None of these ideas are discoveries. No one can discover that the world is a machine (not least because it turned out not to be) any more than we can discover that the brain is a computer (which it most surely is not). These are dogmas, within whose matrix discoveries are made, and such dogmas are optional in the case of language, as the case of Chomsky shows. Dogmas are not answers to questions but rather the very agenda that determines which questions are to be asked. No one knew anything about how the world might actually function as a machine when they posited that it actually was one: it was an imaginative (and for a time, fruitful) idea that turned out to be completely wrong. The notion of the brain as a computer (or of a sufficiently complex computer as a brain) is a similarly imaginative idea. Dogmas, it should be recalled, are not intrinsically bad, since we cannot function without them—one cannot discover that reason is good—but dogmas become a problem when they are treated like findings.

Why do we cling fanatically to imaginative ideas like the brain-as-computer or computer-as-brain when we do not have to? People still think that Newton proved the new mechanical philosophy right with his mechanics, when in fact he completely disproved it by giving an account of gravity that lacked any mechanical component. After gravity came forces of various kinds (force described an “action at a distance,” which was the very antithesis of the mechanical philosophy), and finally in the twentieth century, with the paradoxes of quantum mechanics, the nature of matter became not only totally nonmechanical but literally unimaginable.

We are in a similar situation today: we keep telling ourselves that machines are becoming more like minds, and that we are discovering that minds are just like machines (computers). And yet, just as Newton’s theory of gravity scuttled the project of describing the world as mind-and-machine (though many fail to understand this), human language—with its ability to be ambiguous, express freedom, and get it right (neither through compulsion nor by accident)—remains to this day a glaring reminder of the total inadequacy of the mind-as-machine (or machine-as-mind) model of intelligence.

One final example: Physicists do not ask what the “parts” of a field are or imagine that we can somehow do what a field does by assembling parts corresponding to that field. It is “fields all the way down,” as it were. We cannot see a field or describe it, other than to say where it is and what it does on its own terms. If one could make iron filings line up around an object in a characteristic magnet pattern using airflow manipulation (imagine a box housing thousands of invisible nano-fans and nano-vacuums), it would not make that object a magnet or duplicate a magnetic field. You could call it an “artificial magnet” if you wanted to, but that would be a meaningless name. What human beings have called the spirit, the soul, the heart, consciousness, reason, or the mind should be thought of in that way: one does not create a living being merely by building a machine that imitates some of its effects.

Traditional thinkers described the soul (under whatever name they gave it) as a reality that existed in a hierarchy of realities, and one of the soul’s functions was to give its human bearer the ability and responsibility to mean what he or she says. If human beings were just “parts all the way down,” no one could mean anything at all, since an intention, like a field, cannot be produced mechanically. That is why language remains a thumb in the eye of the mechanistic view: language is nothing if not meaningful, and no mere collection of parts could ever mean to say anything.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy