Bazar of Athens when Greece was under the Ottoman empire, Edward Dodwell, 1821

Bazar of Athens when Greece was under the Ottoman empire, Edward Dodwell, 1821

The term liberal arts has become increasingly ambiguous due to the disparate ideas and images it evokes among educated people. An important failing of modern education lies in its inabilities to draw distinctions and to define terms, both of which have long been obsessions of the scholastic mind. In logic, we are taught that we can arrive at a definition only through an understanding of the genus and its difference from others in the same genus. The genus of the liberal arts falls under the rubric of education. But what differentiates a liberal education from others in order for us to arrive at the definition of the species of liberal education? The distinction resides in the word liberal, which juxtaposes and contrasts it with a servile education. These terms come out of a premodern understanding of societies and their hierarchical structures. A liberal education was given to freemen, as opposed to the vocational training given to the servants and slaves that taught them utilitarian skills, so they could provide the goods and services society needed. Such skills and crafts could be learned through apprenticeship and did not require the rigorous training of the mind.

A liberal education in the premodern period prepared a student for three essential occupations: theologian, lawyer, and physician. The theologian was the doctor of the ills of the immaterial body, the lawyer of the ills of the social body, and the physician of the ills of the physical body. Thus, a society, through a liberally educated elite, had trained minds to tend to the ailments of these three aspects of life on earth: the moral and spiritual life of the soul; the social, commercial, and political life of men living together; and the healthy life of the physical body necessary to enjoy the other two aspects of their lives.

The seven liberal arts divide the world into spirit and matter, quality and quantity, soul and body. An educated person achieved competency in both the life of the mind and the life of matter. The qualitative studies involved the spoken language of literature, especially poetry; the thought processes of the mind that conceptualize, judge, and reason; and the development of an aesthetic sense necessary to effectively persuade, praise, accuse, or defend. The quantitative studies focused on the mysteries of numbers through a mastery of arithmetic and geometry and applying them to music as numbers in time, and then to the supernal world as numbers in time and space.

This holistic approach to education cultivated a mind open to wonderment and a mind reverential to the harmony of creation. The roots of this form of education can be traced back to the mystery religions of Egypt, Babylon, and Greece; its greatest development emerged in the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim civilizations, which embraced these qualitative and quantitative arts to better understand their respective scriptures and the physical world around them. The Muslims considered the revealed books to take two forms: those embodied in the actual words of God, found in the Torah, Psalms, Gospels, and Qur’an, and those found in the book of nature. The first was studied with the tools of the trivium, and the second with the sciences of the quadrivium.

In his useful book Learning to Flourish: A Philosophical Exploration of Liberal Education, Daniel R. DeNicola provides us with a beneficial taxonomy for the contested term of liberal arts. He presents five purposes of liberal education: the transmission of cultural inheritance across generations; self-actualization, leading to a normative individuality; understanding the world and the forces that shape one’s life; engagement with and action in the world; and the acquisition of the skills of learning. DeNicola admits that all five are “detectable simultaneously in most robust conceptions of liberal education.”

First we need to define those two words: education and liberal. A useful definition for the first comes from the nineteenth-century theologian Cardinal John Henry Newman, who in Discourse VI, about “The Idea of a University,” said, “Education is a high word; it is the preparation for knowledge, and it is the imparting of knowledge in proportion to that preparation.” Obviously, this definition begs the question “What exactly is knowledge?” The answer to that demands a good deal of thought, and the metaphysical assumptions imbedded in any given civilization determine their conception of what constitutes knowledge, so it is by no means a facile problem. Nevertheless, let it suffice us for now, as it serves as a common-sense understanding of education. As for the word liberal, Aristotle provides us with a definition in his Rhetoric: “Of possessions those rather are useful which bear fruit; those liberal, which tend to enjoyment. By fruitful, I mean, which yield revenue; by enjoyable, where nothing accrues of consequence beyond the using.”

The Qur’an mentions the word knowledge over one hundred times; the word think, or reflect, has sixty-eight mentions. The first word revealed to the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ was ‘read.’

Thus, a liberal education involves the student acquiring the preparation for knowledge, and the teacher imparting that knowledge, based upon the student’s preparation at each stage, through the mechanism of scaffolding or apperception that is done for its own sake, and not for a means of sustenance. Once this is accomplished, real learning can begin; in other words, after a didactic phase, the real learning by intellectual midwifery, or the maieutic process, can begin. This way, we learn to live a fulfilling purposeful life rather than learn to earn a living.

In terms of preparation, I would like to offer an expression from Imam al-Juwaynī, the teacher of Islam’s greatest scholastic master, Imam al-Ghazālī, who lived in the eleventh century and later came to be considered the Aquinas of Islam. Imam al-Juwaynī states,

You cannot acquire knowledge without six elements; I will explain them with brevity:

A quick mind, zeal, a foreign land, an immense effort, a professor’s inspiration, and a long lifespan.

Interestingly, these couplets, which are found in many Muslim works, appear almost seventy years later in a slightly altered form in Latin by Bernard of Chartres, who says,

Mens humilis, stadium quaerendi, vita quieta, Scrutinium tacitum, paupertas, terra aliena.

This translates to “A humble mind, zeal for learning, a quiet life, silent investigation, poverty, a foreign land.”

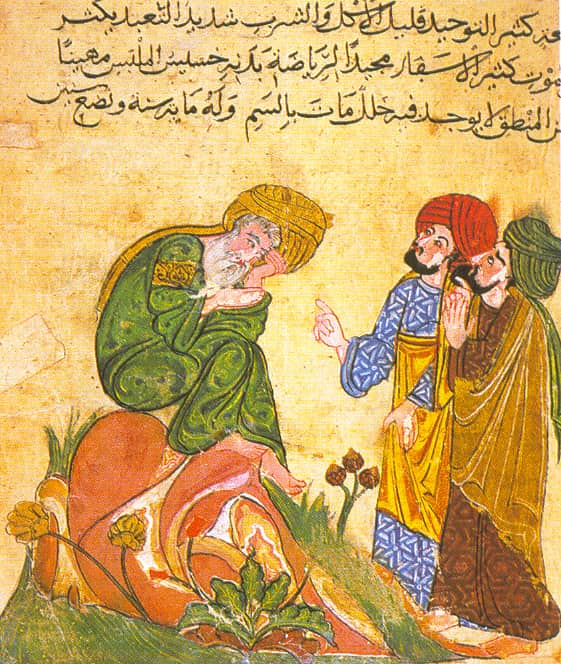

Depiction of Socrates by thirteenth-century Seljuk illustrator

Civilizations rise out of foundational texts. Without Homer, the Athens of Solon or Pericles may never have existed, not to mention the Athens of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. The Bible enables a great Jewish tradition of scholarship to emerge, and when translated into Latin, it gives rise to a unique European Christianity. As Christians rediscover Athens, an extraordinary synthesis occurs that marries Athens and Jerusalem. Christianity and Hellenism are the spiritual basis of Western civilization, and centuries later, as these two traditions begin to wither from neglect and recede into the background, the loss of reason and revelation takes a greater and greater toll on the generations devoid of them, culminating in an evaporation of the immaterial glue that held the fabric of society together.

Beginning in the eighth century, the Islamic civilization runs parallel with the Western, and in many instances intersects profoundly with it. It is also bestowed, like Christian civilization, with a foundational text—the Qur’an—which at its heart is a call to knowledge, study, and devotion. The Qur’an mentions the word knowledge over one hundred times; the word think, or reflect, has sixty-eight mentions. The first word revealed to the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ was “read.” The Prophet ﷺ said, “Seeking knowledge is incumbent upon every Muslim man and woman.” In one tradition, he states, “Seek knowledge, even unto China.”

It was during the life of the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ that the seeds of the synthesis between Athena and Medina were planted. This was also the time of the reign of one of the most notable European popes: Gregory the Great, whose Gregorian mission to the pagan Anglo-Saxons of Britain would transform a wild Germanic people into one of the great learned peoples of the world. Deuteronomy 18:18 says, “We will raise a prophet [Muĥammad] like unto thee [Moses].” As an inheritor of the Mosaic tradition, the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ initially wanted to align with the Jews of Medina, as he saw them as natural allies. While at first they proved supportive of him, with a few exceptions, they remained largely intransigent, failing to recognize their own prophesies in him. He then attempted an alliance with the Christians, and during the vast and devastating war that was raging in the region between the Greek Christians and the pagan Persians (who were allied with the Jews against the Christians), the Prophet ﷺ sided with the Greeks.

A. J. Arberry, a twentieth-century British scholar of Islam, correctly renders the thirtieth chapter in the Qur’an, “Rūm,” as “The Greeks.” His translation of the chapter’s opening lines says:

Alif Lam Mim

The Greeks have been vanquished

in the nearer part of the land;

and, after their vanquishing,

they shall be victors

in a few years.

To God belongs the Command

before and after,

and on that day the believers shall rejoice in

God’s help; God

Helps whomsoever He will; and

He is the All-mighty, the

All-compassionate.

The believers rejoiced in the victory of a people of the Bible over the pagan Persians. In a hadith related in the Kanz al-¢ummāl, the Prophet ﷺ said, “The Greeks are your friends, as long as good remains in the world.” He also said, “Wisdom [the great pursuit of the Greeks] is the lost vehicle of the believer; wherever he finds it, he has better right to it.”

The subsequent generations of Muslims absorbed Greek thought, and as its power began to overwhelm the lucid revelation of the Prophet’s Semitic truths, with their essential yet universal simplicity, and as the rationalists began to side with Athena (reason) over Medina (revelation), the Sunni response was to recognize the great good in Greek learning but to place restraints on its sovereignty through a rigorous methodology that preserved the authority of revelation in its own domain over reason, while asserting the authority of reason in its proper place. The synthesis that emerged acknowledged reason’s importance and place in the areas of natural science, mathematics, and metaphysics rooted in revelation but maintained the importance of revealed truths unknowable by reason alone. These were the two wings that enabled Muslim civilization to soar for centuries.

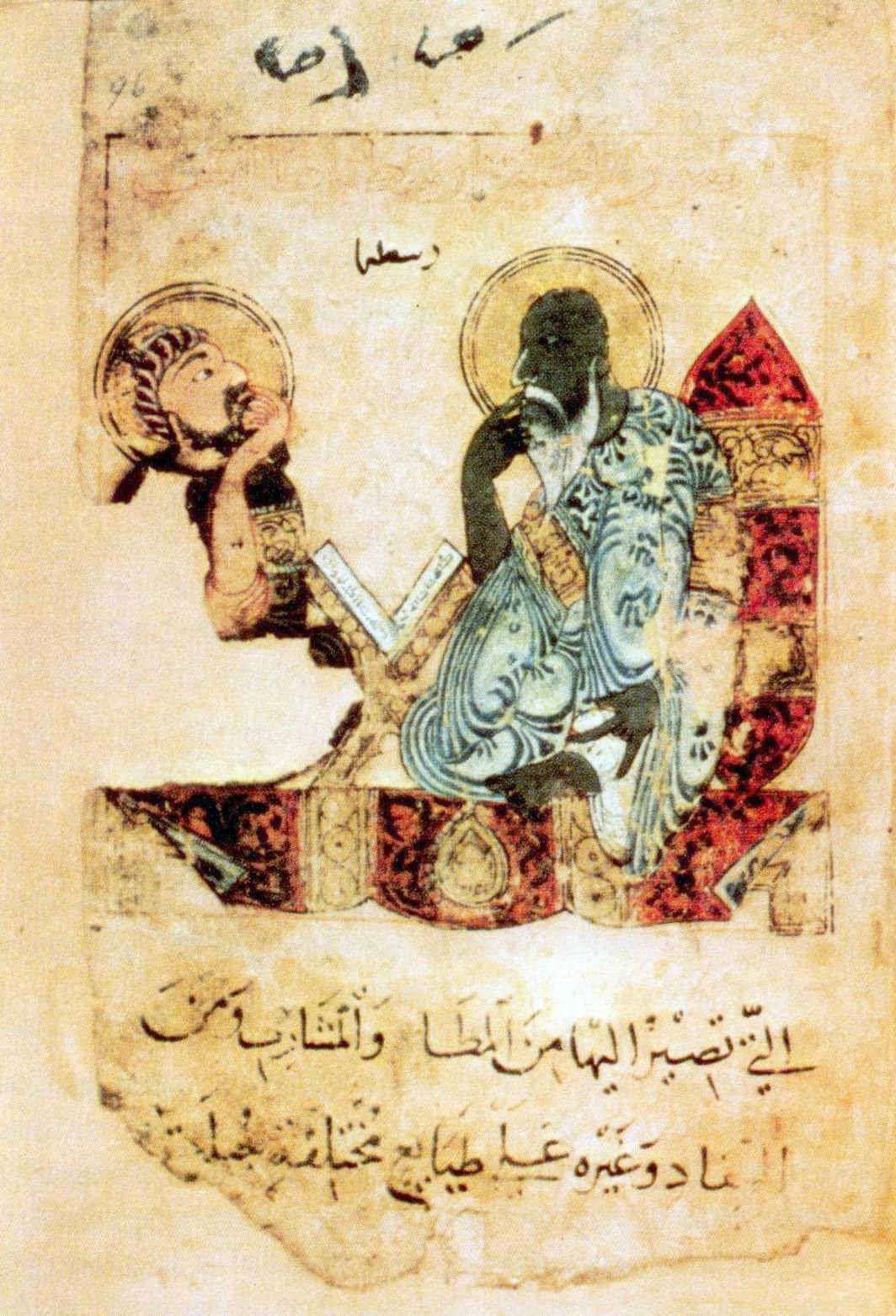

Westerner and Arab practicing geometry, fifteenth century

The pursuit of knowledge became a major obsession of the Muslim world. In his book Knowledge Triumphant, the Jewish historian Franz Rosenthal argues that the Islamic civilization is unique in history for having as its raison d’être the discovery, preservation, and transmission of knowledge. But the concept of knowledge included what a man believed, what he considered good or bad, and whether he had clear standards he was willing to live by. Hence, the idea of an education included moral, intellectual, and spiritual training.

In his book Arabic Thought and the Western World, Eugene A. Myers remarks about Imam al-Ghazālī that his

first contribution to Islam was to bring education into an organic relation with a profound ethical system. He taught that the material gains could not bring happiness without a moral and spiritual reawakening. Education must then not be limited to imparting knowledge; it must stimulate the moral consciousness of the individual.

In the same book, Myers further reveals the immense influence Athens had on early Muslims, as the great classics of Greek science, mathematics, logic, and philosophy were translated during the period from 650 to 1000 CE. This historic translation movement, which included translations by many Arab Christians who had studied within the Byzantine tradition, introduces several texts that would transform the Muslim world considerably and also create many intellectual crises in the process.

Due to an intense reliance on the Qur’an and the Sunnah (the prophetic tradition), an emphasis on language studies highlights the overall educational direction. Grammar; lexicology; and the collection, study, and preservation of the rich and distinctive Jāhilī (pre-Islamic) poetry become mainstays of early Muslim curricula. Avicenna, who died in 1037, takes the corpus of Aristotle and writes The Shifā’, which is his own version of The Organon, with additions and departures from some of Aristotle’s conclusions. The Shifā’ becomes an important book not only in the Muslim East but in Western Europe, through its translation into Latin. Building upon The Shifā’, al-Ghazālī writes his influential Aims of the Philosophers, which explains in a simpler language the foundations of the Peripatetic tradition. The Shifā’ emerges as a major influence on Jewish philosophical thought as well as on the Christian scholastic tradition. Al-Ghazālī then introduces logic—which has been central to the Islamic college curriculum—as a prerequisite for theology and jurisprudence. Arabic rhetoric develops in Central Asia and is added to grammar and logic in a triad of subjects, foundational to the Islamic tradition, that become known as the instrumental arts (al-¢ulūm al-ālah) and sometimes as the three arts (al-śinā¢āt al-thalāth). Thus, the trivium becomes fully incorporated into Muslim scholastic tradition. Grammar, however, remains the focus.

Podcast: The Decline of Language and the Rise of Nothing with Hamza Yusuf and Thomas Hibbs

Islamic portrayal of Aristotle, circa 1220

In his singular book The Foundations of Grammar, Jonathan Owens cogently argues that the grammarians of Islam were closer to what we would today call linguists. They studied every aspect of language, including deeply philosophical problems related to language. Owens states that the eleventh- and twelfth-century Arabic scholars should be revisited by modern linguists, as he contends that the Orientalists of the nineteenth century were not equipped to understand many of the issues those scholars were writing about, because the science of linguistics, which is necessary to actually understand them, had not yet emerged.

Muslims developed grammar schools similar to the ones that emerged in the Western tradition, so for the first six or seven years of study, students memorized the Qur’an and learned grammar and diction. Vocabulary acquisition was done through highly ornate fictional stories, known as the maqāmāt. Students often memorized by rote the entire story and the explanatory notes on word definitions. The other element was quantitative studies of the quadrivium, known as the rational arts (al-¢ulūm al-¢aqliyyah).

The Muslim and Western traditions clearly shared the commitment to the liberal arts. However, as Muslims developed greater emphasis on the religious sciences, the liberal arts elements necessary for a fully developed individual began to recede. Grammar studies still relied heavily on literature and poetry, but logic lost its edge as a result of the abandonment of material logic traditionally understood to be essential for a robust training in philosophy, theology, and critical thinking. Rhetoric continued to be taught to a high degree, but the spatial arts of the quadrivium languished and eventually disappeared from religious training.