A Fairy Moon and a Lonely Shore, 1890

In his tragic and tumultuous novel Demons, Fyodor Dostoevsky underscores the dangers he recognized in the Western European modernist ideals that were making inroads into nineteenth-century Russia. One of the main characters of the literary classic is Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky, a liberal utopian of the 1840s who had tutored a group of youths and instructed them in atheistic socialism and secularism. As those pupils grew into adulthood, the conceptual seeds planted in their early education spawned an extreme nihilism and a pernicious ideology of revolution, leading to political conspiracy and murder in their small town. Like demons, those dangerous ideas completely possessed the young ideologues and eventually incited them to commit serious atrocities. In the penultimate chapter of the novel, “The Last Peregrination of Stepan Trofimovich,” we find the former tutor and inadvertent precursor of social upheaval on his deathbed and, having discarded the liberalist idealism of his past, he makes statements of tremendous metaphysical import: “God is necessary for me if only because he is the one being who can be loved eternally.” He continues,

My immortality is necessary if only because God will not want to do an injustice and utterly extinguish the fire of love for him once kindled in my heart. And what is more precious than love? Love is higher than being, love is the crown of being, and is it possible for being not to bow before it? If I have come to love him and rejoice in my love—is it possible that he should extinguish both me and my joy and turn us to naught? If there is God, then I am immortal. Voilá ma profession de foi [There is my profession of faith].1

Contemplation of the essence of Islam reveals love as foundational to the religion and arguably its most intrinsic principle. In the fifth chapter of the Qur’an, God declares to believers that any of them who forsake the religion will be replaced with a people whose most salient description is love of the divine: “He loves them, and they love Him” (5:54), a scriptural phrase that formed the basis of Muslim spiritual discourse for centuries. In addition, numerous Qur’anic verses characterize the righteous and obedient as those whom God loves, such as: “God loves people of spiritual excellence” (2:195, 3:134, 3:148, 5:13, 5:93); “God loves those who repent much, and He loves those who purify themselves” (2:222); “God loves those who fear Him” (3:76); “God loves the steadfast” (3:146); “God loves those who rely [on Him]” (3:159); and “God loves those who act justly” (60:8).

In a hadith related in Śaĥīĥ al-Bukhārī and Śaĥīĥ Muslim, God’s emissary ﷺ teaches that virtually the entire cosmos, by means of its angelic inhabitants, resonates with divine love:

When God loves a servant, He summons Gabriel and says, “Verily, I love so-and-so, so love him.” Thus, Gabriel loves him, and he proclaims in the heavens, “Verily, God loves so-and-so, so love him.” Thus, all the celestials love him, and then those on earth are drawn to him.

Another hadith related in Śaĥīĥ al-Bukhārī provides one of the most fundamental explanations of the religion in the entire hadith corpus, and it indicates that authentic religious experience is, as it were, dyed with the color of love. The Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ said that God states,

Whoever shows animosity to a saint of Mine is someone against whom I declare war. My servant draws nigh to Me with nothing more beloved to Me than that which I have made obligatory upon him, and My servant continues to draw nigh to Me with supererogatory devotional acts until I love him. And when I love him, I become the hearing with which he hears, the sight with which he sees, the hand with which he seizes, and the foot with which he walks. When he asks of Me, I most certainly grant him, and when he seeks My refuge, I most certainly protect him.

Here, the point of departure and overarching theme is sainthood, a rank so sublime that divine wrath awaits any who transgress against its folk. Naturally, one desires to know how to reach such a station. Therefore, the hadith proceeds with the path to that lofty destination: obedience to the divine command. Yet the language does not depict a dry and mechanical religious ethos; rather, devotional acts are “beloved” to God and open the doors of “drawing nigh” to Him. The teleological particle ĥattā (until) signifies a destination; steadfastness in devotion culminates with the quality most intrinsic to sainthood: love (“until I love him”). Thus, in Islam, love is the telos of all religious practice and its true animating force.

The prophetic description ends with God’s promise that all needs of saints will be fulfilled through their supplication. However, before this divine guarantee, the hadith characterizes the saint in a manner at once mysterious and bewildering: “And when I love him, I become the hearing with which he hears, the sight with which he sees...,” statements that denote a radical loss of identity on the part of the servant, who apparently can no longer identify with personal whim or ego but identifies only with the divine will and preference. Love of God, according to the prophetic tradition, annihilates one’s sense of identity in a way that can only be described as mystical. The saint becomes alienated from his ego and replete with the remembrance of God, to the extent that only the remembrance of God moves him to act. Therein lies the implication of God’s love for the saint, a direct consequence of “He loves them, and they love Him.”

It also implies the saint’s love for God. Imam al-Ghazālī maintains that a full comprehension of the divine names revealed in the Qur’an requires the devotee not merely to understand and believe in them but to imitate them in an appropriate way and metaphorically “share” in their meanings—that is, to inculcate in oneself the human virtues that reflect the divine perfections. “Mirroring” God’s attributes through such ethical mastery represents the saint’s true achievement, the sine qua non of which is falling in love with God, as al-Ghazālī explains: “It is inconceivable that a heart be filled with high regard for such an attribute and be illuminated by it without a longing for this attribute following upon it, as well as a passionate love for that perfection and majesty, intent upon being adorned with that attribute in its totality—inasmuch as that is possible to one who so esteems it.”3 Perhaps no quality better describes the substance of sainthood than passionate love of God.

Moreover, love of God necessarily translates to benevolence and sincere empathy. In Al-Maqśad al-asnā (The most splendid aim), Imam al-Ghazālī lists the ninety-nine sublime names of God and, for each divine name, explains its meaning and describes the virtue one must cultivate to achieve its temporal reflection. Regarding the sublime name al-Wadūd (the supremely loving and kind), he states that a servant reflects that name by desiring for others what one desires for oneself. He continues, “The perfection of that virtue occurs when not even anger, hatred, and the harm he might receive can keep him from altruism and goodness. As the messenger of God—may God’s blessing and peace be upon him—said, when his tooth was broken and his face was struck and bloodied: ‘Lord, guide my people, for they do not know.’ Not even their actions prevented him from intending their good.”4

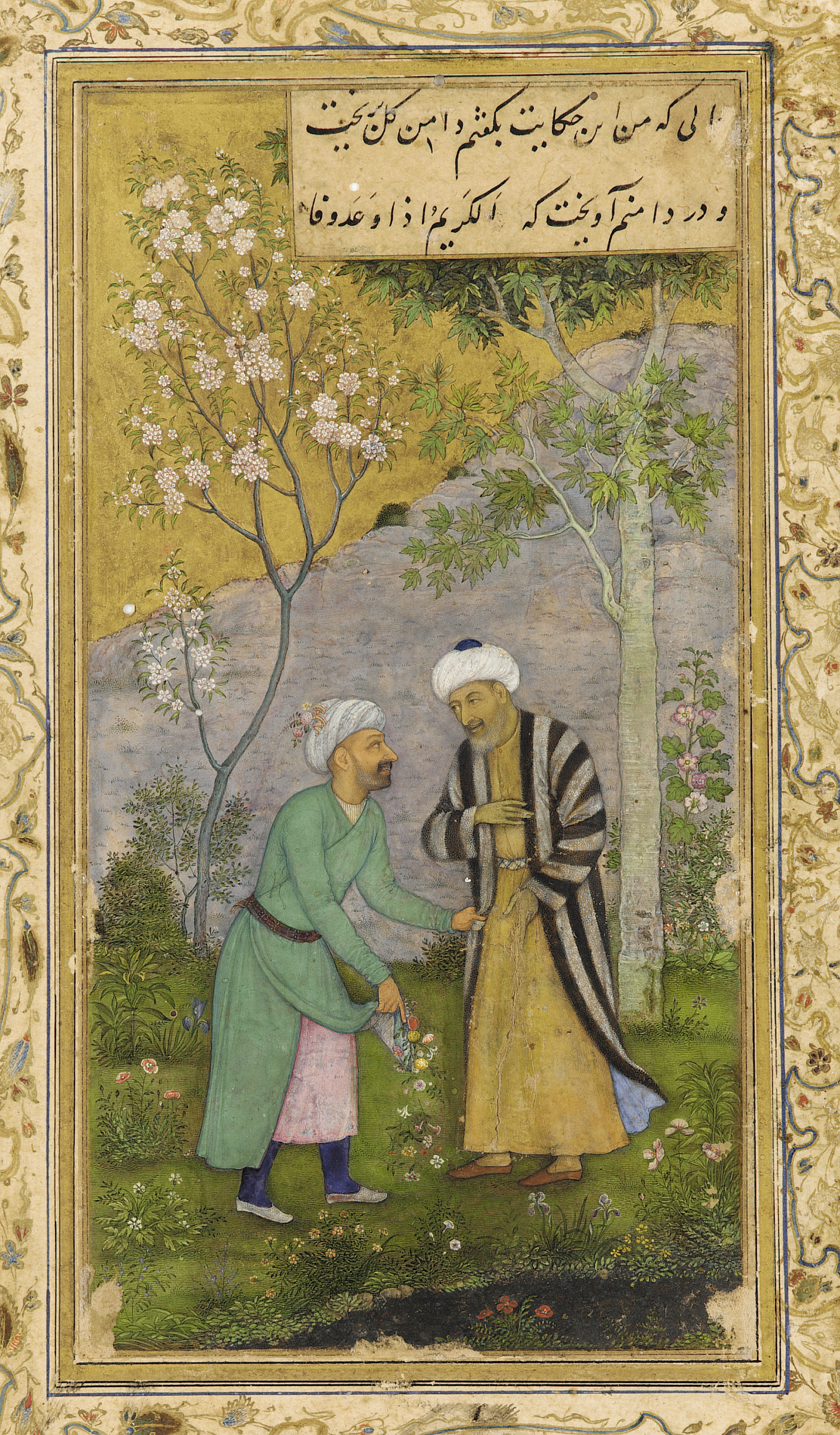

Sa'di in a Rose garden, Govardhan, c. 1645

The animosity, blatant oppression, and constant belligerence of his pagan enemies could not deter the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ from being a perfect human reflection of the divine name al-Wadūd. Certainly, with divine sanction and facing the political exigencies of his time, he defended himself and enjoined his community to military combat when necessary, and always with perfect justice, yet his blessed heart and those of his companions were never loci of rage or malice. His was a heart of pure light. Thus, his first Friday sermon to the Muslims after the sacred migration to Medina, a sermon in which he laid the very foundations of the nascent Muslim community and polity, included “Love all that God loves, and love God from the very depths of your hearts,” as well as “Love one another through the tender mercy of God amongst you.”5

Similarly, the glorious conquest of Mecca, in which he defeated those hostile enemies and therefore had the political power to take full retribution, was a moment of heavenly compassion and forgiveness, as he announced to those who had oppressed him for years, “I shall say to you all as Joseph said to his brethren: There is no blame upon you today.”6 The simile invoked a fellow noble prophet who perfectly signified the divine name al-Wadūd. When Joseph (peace be upon him) was a young boy, his brothers kidnapped him and left him in a well to be sold into slavery. Years later, when reunited with them in adulthood and while in a position of political authority, Prophet Joseph (peace be upon him) also demonstrated sublime and heavenly compassion rather than reprisal: “He said, ‘There is no blame upon you today. May God forgive you; He is the most merciful of those who show mercy’” (12:92).

In addition to such supreme kindness, Prophet Joseph (peace be upon him) exemplified the pinnacle of human beauty, a theme that formed the basis of a work of literary genius by the fifteenth-century Persian scholar and poet ¢Abd al-Raĥmān Jāmī, Yusuf and Zulaikha, an allegorical poem of romantic love and its transfiguration into love of the Divine. Jāmī’s essential message aims to expel illusion from the heart and to redirect the heart only to God, who alone possesses absolute and eternal beauty. In the prologue to the poem, he explains that when God created the universe, each particle became a mirror of His splendor, such that every manifestation of beauty in this world, whether object or person, is in reality a drop that reflects the endless ocean of divine beauty. Whenever a person falls in love, the reflection of God’s eternal splendor captivates their heart, as Jāmī notes, “It is the love of this beauty which quickens the heart and fills the soul with rapture. Knowingly or unknowingly, each heart that loves is in love with it alone.”7 (This mystical insight applies to various forms of worldly love, not just to romantic love; the tender love between parent and child, for example, arises from an inexpressible manifestation of beauty.) For Jāmī, the human perception of beauty and the experience of love represent a window to perceive ultimate reality.

The fascinating case of Zulaikha in the fable will not be treated in this essay; readers may discover it for themselves. But let us consider Jāmī’s message on the tongue of Prophet Joseph (peace be upon him) addressing Bāzighah, a fair maiden of Egypt who had heard of Joseph’s indescribable beauty and, upon seeing him, lost consciousness. When she came to, she was in complete awe of him, and Joseph (peace be upon him) said,

I am the handiwork of that Creator, in whose ocean I am content to be the merest droplet…. Hidden behind the veil of mystery, his beauty was ever free of the slightest trace of imperfection. From the atoms of the world he created a multitude of mirrors, and into each of them he cast the image of his face; for to the perceptive eye, anything which appears to be beautiful is only a reflection of that countenance. Now that you have seen the reflection, make haste to its source; for in that primordial light, the reflection is entirely eclipsed.8

Bāzighah replied, “You have raised the veil from my desire, and guided me from the mote in the sunbeam to the sun itself. Now that my heart is open to this secret truth—that falling in love with you is a mere allegory of reality—it is better for me to cease dwelling in vain appearances.”9 Spiritually awakened, Bāzighah renounced this world and spent her life in devotion to God, feeding the poor and counting rosary beads in her hand in remembrance of God. When she died years later, she left this world “beholding the splendour of the beloved.”10

The secret of love and beauty in the world is their universal summons for man to pursue the way of prophets; Bāzighah’s enlightenment translated to a life of piety, charity, and devotion to God. According to the Qur’an, authentic love of God entails emulation of the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ and hence observance of the sacred law, which in turn opens the gates of divine love; “Say: If you truly love God, then follow me, and God shall love you and forgive your sins” (3:31). This existential purpose answers the perennial question of philosophy: “Why is there something rather than nothing?” The esteemed twentieth-century Muslim scholar and mystic Shaykh ¢Abd al-Rahman al-Shaghouri, when asked by a student why God created the universe, replied, “That there might be love.” The student, contemporary scholar Nuh Ha Mim Keller, explains the response in the context of his mentor’s life of adherence to the sacred law of Islam:

For [Shaykh ¢Abd al-Rahman], Allah was the First and Last, the Manifest and the Hidden. Man shows his love for the Manifest by interactions with His manifestations that make up the phenomenal order of the world, a stage upon which the provisions of the Sacred Law are acted out. There was no real conflict between love of Allah or other than Allah unless one took the manifestations themselves as the object or end of one’s love—not when they were a means to love Him who is Manifest in them through obeying His will, which included both loving certain manifestations, and striving against others.11

For the great saints of Islam, implementing the sacred law serves to express love and to deepen their perception of beauty. It paves the luminous path of attaining the everlasting love of God. In our age of angst and fury—when ennui, despair, and ideological whim infect so many minds and possess so many hearts—the remedy lies in faith and piety rooted in divine love.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy