IV

The limitations of naturalism and empirical science in understanding being can be traced back to assumptions formulated by the eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant. Atheist philosophers tend to believe that Kant’s objection to the arguments for God’s existence was so devastating that it rendered the entire question philosophically irrelevant. In Kritik der reinen Vernunft (Critique of Pure Reason), Kant asserts that ontological arguments are tautological or analytic, maintaining that being is not a real predicate. Existence, says Kant, does not add anything to the concept of a thing—that is, it provides no new information about its properties. A predicate describes or adds to the nature of a subject. For example, if we say, “A triangle has three sides,” the predicate (“has three sides”) tells us something essential about the nature of a triangle. However, Kant argues that being (existence) does not function in the same way as these predicates because it does not describe or modify the subject. For instance, says Kant, the concept of one hundred dollars in the mind is identical to one hundred dollars in the real world; the concept does not change whether the dollars exist or not, and the dollars do not gain any new intrinsic property when they move from concept to reality. Thus, he concludes that existence adds nothing to the concept and remains only the instantiation of that concept in reality.22

Despite the contention of many atheist philosophers that Kant’s objection rendered the question of God’s existence irrelevant, countless philosophical debates continue to this day. Not long ago, I watched a lengthy debate online between the atheist philosopher Graham Oppy and the Christian philosopher Edward Feser, who were vigorously discussing their own writings, which document numerous contemporary arguments and counterarguments regarding God’s existence. One can also point to the works of Alvin Plantinga and William Lane Craig, as well as numerous contributions from non-Western philosophical traditions, all of which continue to engage deeply with this enduring question.23

A pervasive double standard in modern philosophical discourse concerns the disproportionate level of scrutiny brought to arguments for God’s existence compared with other metaphysical claims.24 The critique demands that any argument for God’s existence must meet rigorous empirical or logical criteria, such that it provides the certainty one expects from a scientific law or a mathematical theorem. Yet this demand is hardly invoked when analytic philosophers disagree on significant matters ranging from the nature of causality, modality, and identity to questions about the mind-body problem, the nature of mathematical objects, and the interpretation of quantum mechanics. These disputes do not lead philosophers to dismiss their own discipline as futile because they do not meet empirical or logical criteria; rather, the disputes are seen as intrinsic to philosophical inquiry. Yet when debating God, the philosophical dispute itself invalidates the argument for God’s existence.

The case of Kurt Gödel’s ontological proof for the existence of God reveals much about the double standard. Gödel, one of the most influential mathematicians and logicians of the twentieth century, developed a formulation of the argument based on modal logic and axiomatic reasoning.25 Gödel’s proof follows the formal rigor expected in mathematics and logic, yet it rarely merits serious consideration in mainstream analytic philosophy. Instead, Kant’s critique gets invoked as an ideological shortcut to dismiss any ontological argument and to avoid engaging with the rigorous logical structure and premises of Gödel’s formulation. Such appeals to Kant’s critique function less as substantive philosophical engagements and more as a rhetorical anchor point—a way of foreclosing debate. Philosophers simply do not apply the same epistemic humility and methodological pluralism to arguments for God’s existence that they do to other unresolved philosophical questions. That double standard reveals a deeper philosophical bias: a reluctance to seriously entertain the possibility that God’s existence might be a legitimate metaphysical question rather than a relic of pre-Kantian thought.

An intellectually honest approach, whether one is arguing for—or against—the existence of God, would begin from a set of assumptions or certainties. Even though contemporary philosophers may be reluctant to invoke the notion of first principles, such assumptions remain inescapable. A more productive approach, then, would be to acknowledge these foundational certainties explicitly and undertake a thorough analysis of them.

V

Beginning with a set of assumptions about being that are different from Kant’s, we can consider the many arguments for God’s existence in the Islamic tradition, especially those of Avicenna and Mullā Śadrā, which stand out as the most salient. Avicenna presents what can be called the most sophisticated “onto-cosmological” proof in Al-Ishārāt wa al-tanbīhāt (The pointers).26 It answers a key question: Can a series of contingent beings, even if infinite, explain itself without requiring something beyond it? That is, what matters is the distinction between contingency and necessity and the metaphysical difference between that which must exist and that which might not have existed. Now, physicists like Stephen Hawking may invoke the “no-boundary proposal”—the idea that space-time is not delimited by an original singularity—to support the notion of a self-caused universe.27 However, the empirical validity of such a speculative extrapolation by scientists and philosophers from current physical theories remains widely contested and shows the double standard regarding the point about “evidence.” In any case, for Avicenna, contingency can only become necessity through another entity, which is a point of deep contention between contemporary naturalists and nonmodern philosophers (roughly, philosophers before Descartes). Unlike Avicenna and other nonmodern philosophers, naturalists may accept an initial causal state that is both natural and contingent—contingent either because the entities involved are themselves contingent or because some of their properties are.28

For Avicenna and many others in the Islamic tradition, by contrast, contingent beings, by definition, lack what can be called eternal necessity, meaning they require an external cause that possesses necessity in itself. Only being (wujūd) fits this criterion. To illustrate the concept of eternal necessity, consider a triangle, which possesses an essential but not an eternal necessity. That is, in every possible world, the definition of a triangle will hold, but this does not necessitate its eternal existence. That definition, as a logical truth, holds in every conceivable world—whether on earth or in heaven. However, the triangle as an actual existing thing does not necessarily exist at all times or in all worlds, which means that its concept is necessary but its existence is contingent.

So, even if we grant an infinite chain of contingent beings, the series cannot become necessary except through another cause. Avicenna’s argument from contingency ultimately demonstrates that a series of contingent beings must terminate in a being whose existence is necessary in itself—that is, God.29

We should note that in contrast to philosophers like Avicenna, who use the concept of the Necessary Being (wājib al-wujūd) to establish God’s existence, there are those such as Śadr al-Dīn al-Qūnawī who challenge the adequacy of this approach. Al-Qūnawī argues that the idea of a first cause or Necessary Being, based on the claim that the chain of causality originating from contingent things cannot regress indefinitely, does not constitute a conclusive proof. Moreover, it fails to illuminate the true essence of ontological necessity and contingency.30

According to al-Qūnawī, the concepts of contingency and necessity should be understood in terms of the relationship between the limited and constrained (muqayyad) and the limitless and absolute (muţlaq). More specifically, he seeks to replace the Avicennan distinction between contingency and necessity with a more nuanced framework: the distinction between determination (ta‘ayyun) and non-determination (lā ta‘ayyun). The more specific and determinate a thing is, the more limited and constrained it becomes in relation to other things and, consequently, the more it depends on the principles that define its particular mode of determination. Thus, every act of determination implies a restriction in relation to the underlying, unrestricted principles.

This can be illustrated by how light gets refracted through a prism. If one were to ask what causes the different rays of light produced in the prism, an answer might be the prism itself and, ultimately, the sun. This follows Avicenna’s line of reasoning, in which each effect is traced back to a first cause. Al-Qūnawī, however, shifts the focus. Rather than asking what caused a specific ray of light, he asks how such a ray can be a determined expression of undetermined light. Thus, al-Qūnawī’s critique does not deny causality but rather deepens metaphysical analysis. That is, instead of proving God by rejecting infinite regress, he seeks to show that every limited and determinate thing points back to the unlimited, not just as its origin but as its ontological ground.

For this reason, al-Qūnawī even identifies Being—conceived as the immediate principle of existence—with “determination itself.” Being, in his view, encompasses all potential determinations within itself without being confined to any specific mode. However, while al-Qūnawī considers all entities dependent on this “first determination” (al-ta‘ayyun al-awwal), he does not regard it as the ultimate foundation of reality. This is because the first determination still bears some degree of contingency, arising from its own determinate nature. As such, it excludes the “indeterminate” or “nonmanifest” and cannot serve as the absolute principle of all reality, since it does not encompass reality in its entirety.

Consequently, al-Qūnawī asserts that the fundamental principle of reality must transcend all limitations, making it absolute, infinite, and all-perfect. True absolute freedom resides only in the state of complete non-determination, which alone describes the Divine as the indeterminate reality underlying all determinate things. For al-Qūnawī, the deepest way to understand the relationship between contingency and necessity is to recognize that all determinate realities are necessarily grounded in non-determination. This harks back to the notion of divinity as meta-personal that was delineated earlier.31

Be that as it may, another argument that I find compelling, provided one accepts the distinction between the concept and reality of Being, is Mullā Śadrā’s argument from the primacy of being, best understood using the analogy of the “dark room” as described below.32 This argument can be structured as follows:

Premise I: Everything other than being actualizes its reality through the mediation of Being (without Being, entities would be pure non-existents). Likewise, traces and accidents of things become real through the intervention of Being.

Premise II: A principle that acts as an agent of making everything else real must be “real by itself,” which is to say, it must be principial or primary (aśīl).

Conclusion: Being is real by itself—that is, principial. Its actualization occurs in and by itself, and it can dispense with the determining mode (ĥaythiyyah taqyīdiyyah) while “existing” in contrast to other entities. That is to say, to predicate “being” of Being, we do not require any conditioning factor, since it is a self-existing principle by definition.

Let us illustrate Mullā Śadrā’s argument from the primacy of being with a relatable example. Imagine a dark room where nothing is visible. Now, suppose we turn on a lamp. The moment light spreads, objects in the room become visible. Without light, those objects still exist, but they lack actualized visibility; they remain in a state of darkness, effectively nonexistent from our perspective. Similarly, consider how this analogy maps onto Mullā Śadrā’s argument:

Premise I: Just as objects in the room require light to be seen, all entities require being to be real. Without light, the objects might as well not exist for us; similarly, without being, entities are mere non-existents.

Premise II: The lamp itself does not depend on any other source of illumination to be light; it is the origin of visibility in the room. Likewise, being or existence does not derive its reality from something else—it is real by itself, making everything else real.

Conclusion: Light is self-illuminating as it does not need another source to be what it is. Similarly, being does not require an external condition to exist. It is self-subsistent, while everything else derives its reality from it. Just as we do not need to impose an additional condition to say that light is bright, we do not need an external factor to predicate existence of being, since it is real by itself.

This analogy illustrates why, for Mullā Śadrā, being is the fundamental reality, and everything else depends on it.33 It means that, contra Kant, Śadrā sees being as a “real predicate,” because it constitutes the very structure of reality itself rather than a mere conceptual attribution. Being is not a static, neutral predicate but an active, dynamic principle. Unlike Kant, who views existence as merely positing something without adding or modifying, Śadrā views being or wujūd as the most fundamental reality. He distinguishes between mental constructs and real existence and contends that every determination and property appears through the intensity and gradation of being.34 For example, existence in its fullest sense, such as divine existence, remains qualitatively different from contingent existence. Śadrā’s doctrine of the gradational nature of being (tashkīk) means reality is not a collection of discrete, static entities but a continuum of different intensities of being. Since all qualities and perfections emerge from this gradation of being, it must be real, not a mere conceptual placeholder.

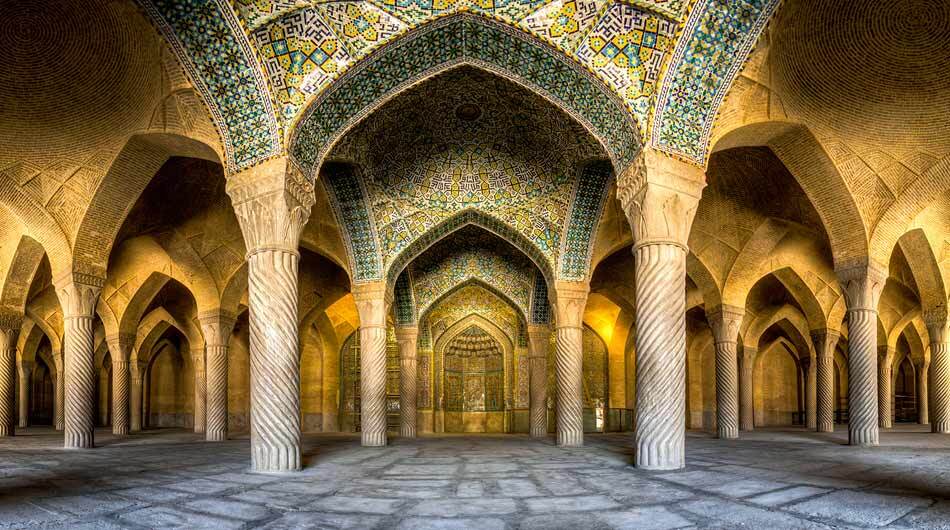

Moving beyond these philosophical proofs, one must take seriously what arises from following a spiritual path—the argument of finding God within. While sacred scriptures like the Qur’an may not present philosophical proofs for God’s existence, they constantly point to natural phenomena and processes as signs (or proofs) of God for those capable of reflection and intellection. Rather than focusing on the mere existence of things, the Qur’an emphasizes the intrinsic order and harmony of the universe, which necessitate recognition of a creator. In doing so, the Qur’an integrates elements of both the cosmological and teleological arguments, reinforcing them with its call to seek God within the depths of the human soul. Sufism, drawing from the Qur’an and hadith, appeals to both visual and auditory intuition, guiding the seeker on a Platonic ascent from love and beauty in the phenomenal world to their eternal archetypes in the divine principle.35

In any case, from Mullā Śadrā’s perspective, Kant’s objection to the ontological argument is flawed because he fails to distinguish between mental and external existence (wujūd dhihnī versus wujūd khārijī). In Śadrā’s philosophy, being is the very ground of reality, and different modes of existence are metaphysically significant. Moreover, Avicenna’s onto-cosmological proof demonstrates God to be not merely necessary for the existence of the contingent world but a metaphysically Necessary Being, which is to say that God’s existence is not simply a matter of definition but an intrinsic ontological reality. All of this underscores the fact that God’s existence remains a topic of enduring philosophical inquiry.