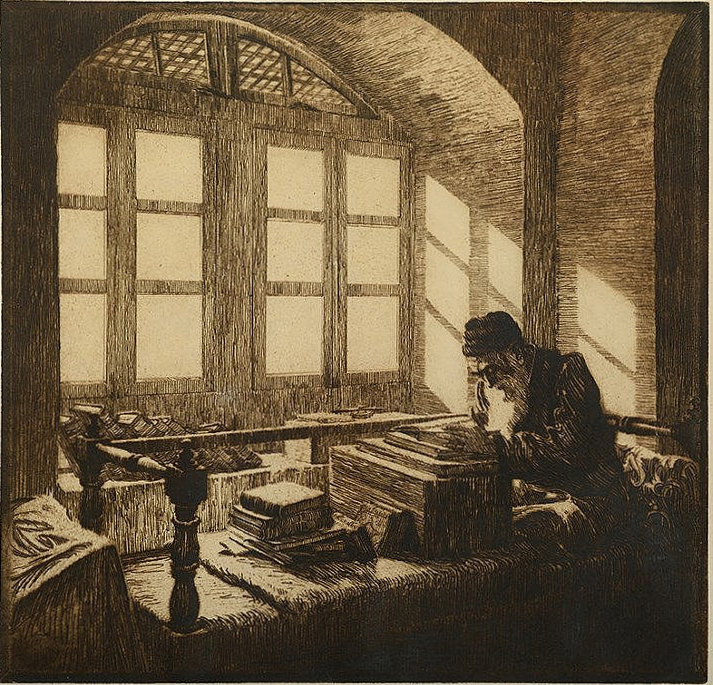

Talmud Torah, Ephraim Moses Lilien, ca. 1900

Robert Alter’s publication of a complete translation of the Hebrew Bible caused a literary sensation. Most English translations of the Bible1 have been the products of committees, so one-man translations, particularly of the whole text, are not common. Moreover, Alter is not a biblical scholar by profession but rather a professor of comparative literature and Hebrew at Berkeley. Alter had gotten into the field of Hebrew Bible studies through a well-regarded book on biblical narrative published in 1981. Persuaded by his editor to follow that with a book on Genesis, he concluded that existing translations were unsatisfactory and so did his own. The rest is the story of a small academic project that got out of hand, something familiar to a great many scholars. His translation of the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, came out in 2004, followed by several more installments until the completed work was published in a handsome three-volume edition in 2018. The work was greeted by general acclaim—along with a certain amount of predictable scholarly harumphing from specialists.

Alter is a literary scholar deeply steeped in English and Hebrew literature with a mastery of English prose style and the rhythms of biblical Hebrew. His concern, as he makes clear in an essay on translation that begins each of the three volumes and in a short follow-up book, The Art of Biblical Translation, is the style and narrative techniques of the Hebrew Bible and how they might best be rendered into English. It is a task, he acidly insists, that the modern translators of the Bible have failed miserably at. His heroes are the translators of the King James Bible and his two favorite medieval commentators, Rashi and Abraham ibn Ezra. His villains are his colleagues down the hall in biblical studies departments and the translations they produced by committee in the second half of the twentieth century.

Why the King James Bible? To start with, the king’s translators were men like him, scholars who knew the languages of the Bible and sometimes also languages like Arabic and Syriac but who were also deeply immersed in the literary culture of their time. In short, they knew the Bible and they knew how to write. They were of an age that produced the great polyglot Bibles and monuments of English style such as Shakespeare, Milton, and The Book of Common Prayer. They also were convinced that the Bible was, word for word, the Word of God, so they followed the Hebrew text as closely as they could, even meticulously italicizing words that had to be added to make intelligible English, as in “I am Joseph,” the copula not being required in Hebrew. To be sure, they sometimes misunderstood the Hebrew and tended to put everything in the same register, of which more later. Still, it is owing to the literalism of the King James Bible’s translators that high liturgical English has a decidedly Hebraic flavor, something that translators of the Qur’an and classical Arabic might well keep in mind, as we will see.

Alter is particularly satisfied that the king’s translators tended to faithfully translate the Hebrew ve as “and.” As any student of biblical Hebrew—or Arabic—knows, ve/wa can legitimately be translated not only as “and” but also as “but,” “so,” and various other connectives, so modern Bible translations usually render ve according to the context. Alter is adamant that King James’s translators were right and the modern translators are wrong. Waving the banner of parataxis, the stylistic device of coordinating clauses without indication of subordination or logical relationship, Alter insists that the biblical authors knew what they were doing with their use of ve and the resulting ambiguities. It is Alter’s insistence on rendering ve by “and” that has been most consistently criticized by biblical scholars. In reply, Alter sputters that he suspects his critics never read Roth, Nabokov, Hemingway, or Molly Bloom’s soliloquy. Point to Alter, I have to say.

Modern translators in Alter’s view have thrown away the baby with the bath water. Seeing the translation problems in the King James Bible, they have started over from scratch. Alter is well aware of the philological achievements of modern biblical scholars, but in his view they have utterly failed to deal with the stylistic and literary aspects of the text, occasionally adding their own errors in the process. Translation errors Alter could have tolerated; bad English, he might have said, is the blasphemy against the Holy Ghost that cannot be forgiven.

Alter, having produced a complete translation of the Hebrew Bible, has put his translation theories to the test. So how did he approach this task, and how well did he succeed? Two factors shape his translation.