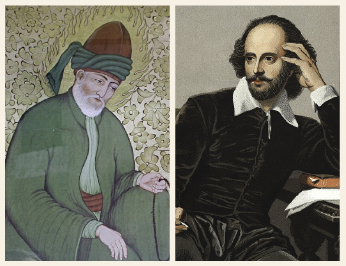

Jalaluddin Rumi (d. 1273) has sometimes been called “the Shakespeare of the East.” The comparison is just: Both authors powerfully shaped the languages in which they wrote—Persian and English, respectively—and both explored the full dimensions of the human experience. Both also showed a particular interest in how seemingly intractable conflicts can be resolved through forms of reconciliation.

We can learn a lot by comparing and contrasting two tales from each of these authors on the themes of regret, forgiveness, and reunion. Both authors appeal to marvels—Rumi to a magical parrot and Shakespeare to an Italian wizard. Both examine the motives of the powerful, whether the general Othello or the Prophet Muhammad’s son-in-law ¢Alī. Themes of unthinking violence and profound repentance, of unforgivable trespass and principled clemency, animate the tales of both. And both complicate the ancient definitions of tragedy and comedy, wherein the former is a bleak story where things fall apart at the end and the latter is a humorous story where things come together at the end.

Rumi’s tale of the greengrocer and his parrot is a warning both against an angry rush to judgment and against overconfidence that the framework of our own lives can be generalized to the lives of others.1 The scene opens in a vegetable shop, the proprietor of which owns a parrot with a dulcimer-like voice. The bird can converse with the customers in human language but can also call like a parrot. It even keeps an eye on the shop when the owner goes out. One day the bird takes flight and clumsily knocks over a bottle of rose oil, which splashes over the absent owner’s bench. When the grocer comes in and sits down, he notices the oil soiling his garments and the floor and figures out what happened. He flies into a rage and beats the parrot about its head, such that its plumage falls away, leaving it bald. The chastened parrot falls silent.

In the aftermath, the grocer is stricken with regret at his ill temper, heaving sighs all day long. The parrot had been an attraction, bringing in customers, and the grocer now confronts an empty establishment. He wishes his hands had been broken so he could not have used them to thump the golden-voiced bird on its head. He starts filling the begging bowls of passing Sufi holy men in hopes of reversing his bout of ill fortune and attempts to bring the parrot back to its old self by showing it a succession of marvels.

Then a completely bald dervish passes by, and the parrot becomes agitated and screeches, asking if the Sufi had also knocked over a bottle of oil. The bystanders, amused, caution the parrot that it cannot assume that it is like the spiritual adept just because of a superficial resemblance.

Rumi’s stories are as multifaceted as a brilliant-cut diamond, and his characters serve as multivalent symbols. Since parrots in Rumi’s Anatolia came from India, they subsisted in exile from their homeland. They therefore became a symbol for the human soul, which is in exile from the divine realm of ideas and plunged into the alien terrain of the material world. Parrots are also marvels, given their ability to bridge the human-animal divide with their speaking abilities. In this latter regard, as well, they resemble the human soul, which has an animal body for its carriage but is capable of the reasoned speech that reflects the Logos of the empyrean. As Rumi said in his discourses, people are “half angel, half animal.”2 Of the grocer’s parrot, he writes, “In addressing a person, it uttered reasoned speech; / In the song of the parrots, it was gifted.” This beautiful creature, with its bright green plumage and its fabulous discourse, mesmerized the grocer’s customers and proved a magnet for his shop, making him prosperous. A balance of the human and the animal in the parrot created this fortunate estate.

The parrot, however, did have its animal, material side, which led to its accidental spilling of the rose oil, which provoked the ire of the vegetable seller. The story focuses on the response to the sins that arise from the material dimension of the human. The grocer responds inappropriately, allowing himself to be overwhelmed by fury and ruin the prodigy he had been given. He torments both another and himself. The bald, mute parrot that results from his berserk frenzy also ruins the grocer’s prosperity. Because the parrot is itself a marvel, he tries to resuscitate it by displaying all sorts of marvels to it, without result. Seeing a marvel and being a marvel are not the same thing. Likewise, donating to itinerant Sufi mystics might be a good deed, but it is not transformative of the soul. The parrot’s voice comes back only when he sees the bald-pated dervish, who it assumes also spilled a bottle of oil.