Apr 28, 2017

Sheath Your Sword

Duke University

Omid Safi's research includes Islamic mysticism, contemporary Islamic thought, and medieval Islamic history.

More About this Author

Duke University

Omid Safi's research includes Islamic mysticism, contemporary Islamic thought, and medieval Islamic history.

More About this AuthorI’m drawn to saintly beings. It’s taken me sometime to figure out why. It’s not about miracles. It’s about heart.

I know that these luminous human beings are still human beings, but I want to figure out how they have become illuminated. I am intrigued by how they struggle with the same urges, desires, hopes, and dreams that we all have — and how that can help all of us figure out how to live more beautifully.

In sorting out these questions, I’ve been searching Rumi’s poetry. One story that really speaks to me is the story of the man who spat on a great saint’s face.

I’ve been teaching Rumi’s masterpiece, the Masnavi, to a class this month. The book is in many ways a roadmap of spiritual growth. It begins with the condition of so many of us: being broken, homesick, cut off, alone, down and out, and unsure of our own worth. The narrative moves through the purification of the heart, the cleansing experience of love, before moving to the state of being a real human being.

The story that the Masnavi tells is the path that all of us have to go through, moving from brokenness to healing, from spiritually feeling worthless and cut off to being wholehearted. That is the whole goal of the spiritual path: not divinity, but full humanity.

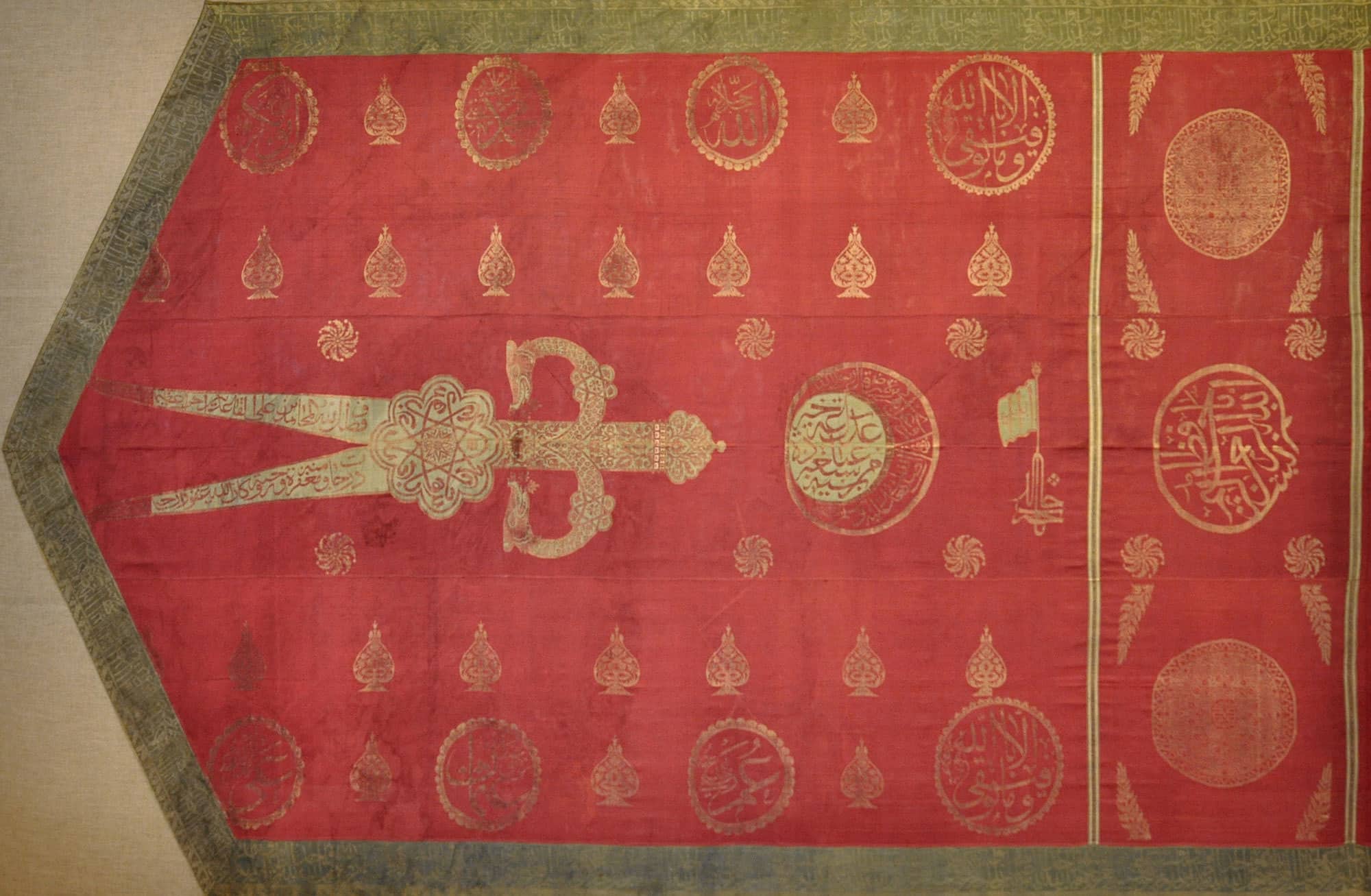

In Rumi’s telling, that state is represented by the saintly Imam Ali, a chivalrous knight who met a mighty warrior, a mountain of man, in a duel. The two engaged in traditional wrestling, until Ali picked up the mountainous warrior, threw him to the ground, and was ready to vanquish him.

The pagan warrior, flustered and humiliated at having been defeated, spat on Ali’s face. Ali calmly got up from the defeated warrior’s chest, put his sword back in his sheath, and walked away. Here’s how Rumi tells the tale:

Learn how to act sincerely from Ali

God’s lion, free from all impurity:

During a battle, he subdued a foe

Then drew his sword to deal the final blow.

That man spat in Ali’s pure face, the pride

Of every saint and prophet far and wide

The moon prostrates itself before this face

At which he spat — this act was a disgrace!

Ali put down his saber straight away

And, though he was on top, he stopped the fray.

The fighter was astonished by this act,

That he showed mercy though he’d been attacked.

The pagan warrior, puzzled, inquired from Ali why he had not finished him. Ali explains that everything he had done up until that point had been for the sake of God. When the warrior spat on his face, Ali got angry. If he were to kill the warrior, it would not be for the sake of God, but as a response to his own anger.

What Rumi is revealing is that the real measure of power is not about brute force, not the ability to lift mountainous weights, but rather the ability to control one’s own impulses. Perhaps “control” doesn’t quite do it. Control implies too much a relationship based on opposition, pushing down, and fighting. It’s more like skillfully channeling one’s ego.

As Rumi says, if the measure of a human being were simply about power, then elephants would be more human than humans! Rather, the model of humanity is to strive in the path of God, yet to channel away one’s selfish desires so that one can be imbued with divine attributes. If we don’t cleanse the cup of our hearts first, it’s like having a muddy cup in which we keep pouring fine tea. The mud does not disappear, but it doesn’t have to be in our cup. I wonder if anger and lust work like this: the only place that they can be dangerous is in our hearts. Channeled away, they are defused.

Ali’s model is not one of pacifism, per se, as it is one in which even fighting is sanctioned as striving (literally: jihad) in the path of God, provided it is not inspired by hatred, anger, or passion. Let’s return to Rumi’s telling of the story, with the champion Ali putting his sword away:

He said, I use my sword the way God’s planned

Not for my body but by God’s command;

I am God’s lion, not the one of passion

— My actions testify to my religion: . . .

Rumi then has Ali say that he is the real mountain of a man, and not some piece of straw who is going to be blown here and there by the “winds” of his passions:

I am a mountain, God’s my solid base,

Like straw I’m blown just by thought of His face;

My longing changes once His wind has blown,

My captain is the love of Him alone.

Here is the mystic, active in this world, even on behalf of justice, “blown just by the thought” of God’s face. We are all moved in life. I wonder what moves us? Is it ego? Greed? Anger? Lust? Desire? Or God’s face?

There is something about this narrative, about Ali’s behavior, that I find awfully assuring. The complete human being, the realized human, the saint Ali still experiences passions. He still struggles with anger. But anger doesn’t have to move him to action. I am relieved to know that the full human being is still dealing with the same emotions and passions that all of us struggle with, perhaps with the difference that he or she can pause and let these emotions pass through them without being acted upon. Perhaps this is what it means to be a fully realized human being, to know one’s own heart and soul well enough to be able to channel these emotions away from the home that should be filled by Spirit.

Had the full human somehow been bereft of these emotions, I would have been tempted to give up, to think that these luminous souls belong to some other realm of existence, a place that we, the rest of us, cannot go to. But no, even the saint still has to deal with these emotions.

There is one last chapter in the story that has a lot of relevance for today’s world. As Ali and the fallen warrior continue their dialogue, indeed their friendship, Ali reveals one last secret to his former foe, his new friend. He talks about the deepest reason why he was unable to kill the defeated warrior. Ali, the saint, says that he looked at the warrior through the glance of compassion, and saw his own humanity reflected in his former foe. Ali saw the fallen warrior as himself.

Addressing the fallen warrior by his own name (Ali), Ali says:

Illustrious one, I am you and you are I

Ali, how could I cause Ali to die!

I wonder about our own world.

I wonder about so many of us, alone.

I wonder about the enmity in our families, anonymity in our workspaces, tension in our communities.

I wonder about war, occupation, poverty, racism.

I wonder if we are willing to commit ourselves to this path — cleansing our hearts of ego, of lust, of anger.

I wonder if we are ready to do so as individuals, do so as communities, do so as nations.

I wonder if we are willing to put our swords (airplanes, tanks, bombs) back in their sheath.

I wonder if we are ready to look at each other in the eye, and see our own humanity reflected in one another.

If we do. When we do. We would be fully human. And then, just maybe, divinity would be fully present.

This article was first published by On Being and is republished here with permission from the author.