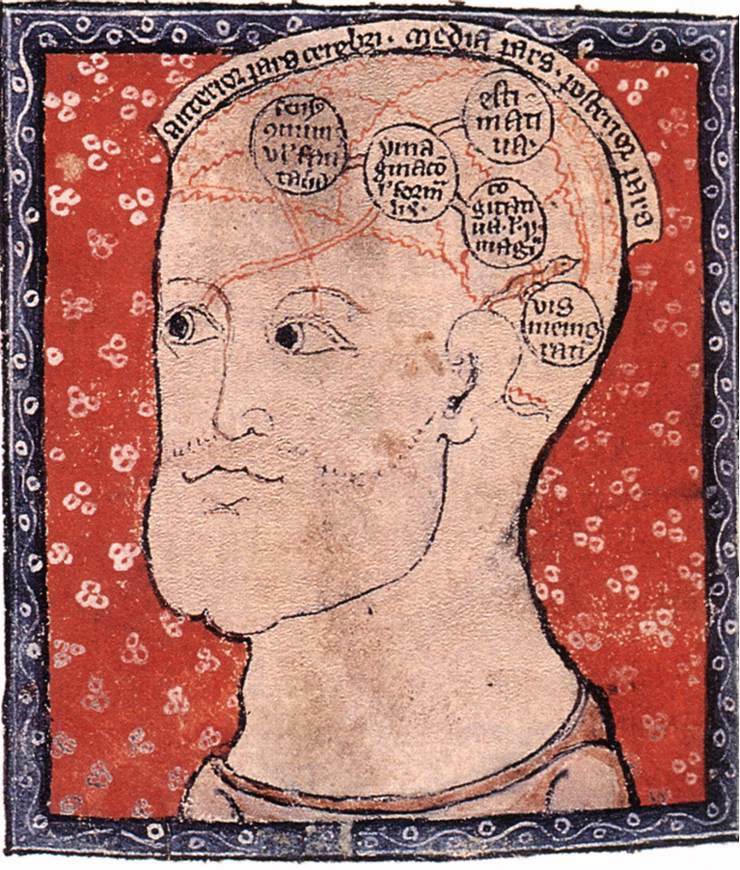

Diagram of the brain, ca. 1300, unknown artist

Few today would deny that the brain holds a preeminent place in the scientific imagination. In modern science, the brain is often seen as the organ of consciousness, thought, and identity. This view, rooted in neuroscience, psychology, and cognitive science, suggests that who we are—our emotions, memories, imagination, and even sense of free will—is fundamentally tied to and determined by the brain’s structure and function. With the rise of brain imaging (e.g., functional MRI and electroencephalograms), neuroplasticity research, and artificial intelligence (AI), the brain has become a new frontier for exploration. Neuroscientific breakthroughs have fueled speculation about everything from mind uploading to brain-machine interfaces, reinforcing the brain’s essential role in discussions about human potential and limitations.

Yet as Matthew Cobb’s illuminating The Idea of the Brain: The Past and Future of Neuroscience demonstrates, despite centuries of scientific inquiry, our understanding of the brain remains remarkably limited.1 The more we learn, the more the brain’s complexity defies reductive explanations. While we have built a solid foundation in neurophysiology, we still lack a clear understanding of how neurons—whether billions, millions, or thousands—interact to generate brain activity.2 To be sure, we know that the brain interacts with the world and the body, processing stimuli through both innate and learned neural networks. It predicts changes in stimuli to prepare appropriate responses and coordinates bodily actions through intricate neuronal connections and chemical signaling. Yet when it comes to truly grasping how neural networks operate at a cellular level or accurately predicting the effects of changes in their activity, we are still in the early days of neuroscience. For instance, while scientists can artificially induce visual perception in a mouse by replicating a specific pattern of neuronal activity, they do not yet fully understand how and why visual perception generates that pattern in the first place.3

How are we able to discuss so extensively an organ whose operations we scarcely understand? Cobb provides an accurate account when he argues that a persistent challenge in neuroscience is the tendency to impose external analogies and metaphors onto the brain, a tendency that reflects a representationalist approach to its study. From Descartes’s hydraulic model inspired by garden fountains to contemporary metaphors drawn from computing and AI, such approaches often obfuscate rather than illuminate our understanding of the brain. A representationalist approach to understanding the brain assumes that the brain functions primarily as a system that creates and manipulates internal representations of the external world. In this view, the brain is like a mirror or model builder that forms symbolic or computational representations of reality rather than directly engaging with it.

While metaphors like these may be unavoidable, an overreliance on them can constrain our thinking about the brain itself. For example, many scientists now recognize that to view the brain as a computer that passively processes inputs is to overlook its active role as an organ embedded in the body, constantly interacting with its environment. More importantly, these models are external projections onto the brain rather than direct insights into its actual workings.

Similarly, the prevailing scientific view is that thought arises, though by mechanisms we do not yet fully understand, from the activity of billions of neurons within the human brain. Surprisingly, however, this focus on the brain is a relatively recent development. Throughout most of history (with some exceptions), human beings have regarded the heart, rather than the brain, as the primary locus of perception and emotion. The influence of this ancient perspective persists in our everyday language. For instance, English expressions like learn by heart, heartbroken, and heartfelt (with parallels in many other languages) reflect a worldview that modern science has largely superseded. Yet these phrases carry a deep emotional resonance, something that becomes clear if one attempts to substitute brain for heart and considers the result (e.g., “brainbroken”).

In any event, similar to other elements in our scientific paradigm, the mechanistic view of the brain goes back to the proponents of the new empirical science in the seventeenth century. Thus, Nicolaus Steno, who was influenced by Descartes, describes the project of neuroscience in the following way:

The brain being indeed a machine, we must not hope to find its artifice through other ways than those which are used to find the artifice of the other machines. It thus remains to do what we would do for any other machine; I mean to dismantle it piece by piece and to consider what these can do separately and together.4

This passage highlights a scientific and mechanical approach to studying the brain. The idea is that since the brain can be understood as a kind of “machine,” we should study it in the same way that we would any other complex machine. We must “dismantle” the brain in order to study its individual components, such as neurons, synapses, and various biochemical processes, so that we can understand their separate and collective functions. By doing this, we may hope to uncover how the brain works in much the same way as the mechanics of any other machine.

However, such mechanistic views of the brain—and, by extension, of the human being as a whole—inevitably raise ethical concerns, particularly in the context of human relationships, where complex emotions are at play. Indeed, comparisons between humans and machines were widely considered deeply immoral since they were seen as threatening the notion of free will. The prevailing argument held that if human choices were merely the result of material processes rather than guided by the spirit, the foundation of morality would be at risk. Many critics even feared that materialists would exploit the machine analogy to lure naive young people into unchecked sexual indulgence. According to one John Witty, the crafty scheme of the materialists would be “first, to Argue themselves into mere Machin[e]s; and afterwards in Letters to the Ladys; to persuade ’em, for what ends ’tis not difficult to determin[e], out of their Immaterial and Immortal Souls.”5 This amusing suspicion expressed in the 1700s actually shows an awareness of a holistic understanding of the human being that contemporary brain science still lacks.