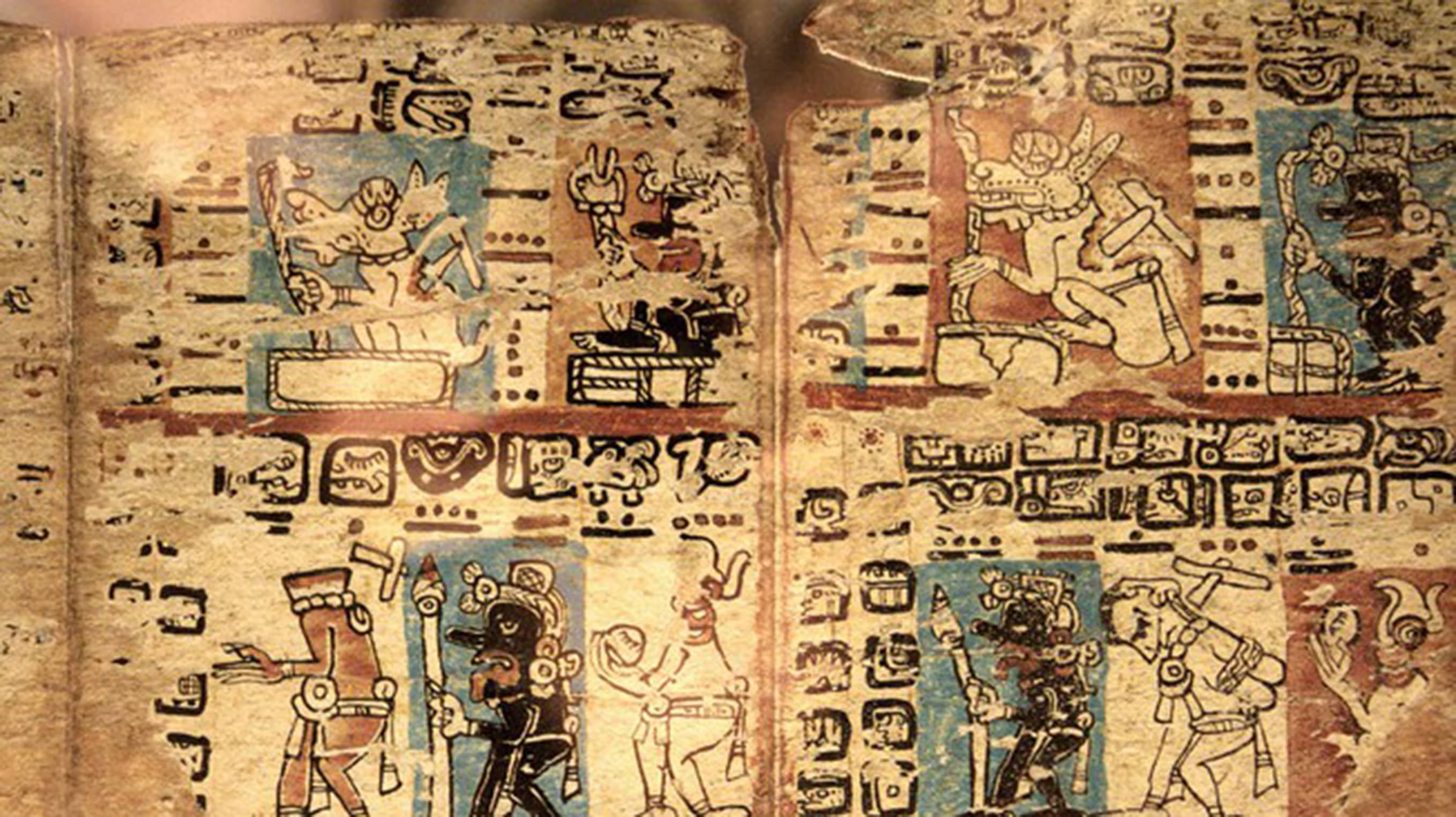

Detail from Madrid Codex, a pre-Columbian Maya book, circa 900–1521 CE

Covenant is an antiquated word, redolent of sacred bonds formed by peoples whose legal traditions were inseparable from their religious beliefs, their ancestral relations of kinship, and their oaths of loyalty. It is a very serious word and, for that reason, does not fit comfortably into the discourse of a world such as ours, which, from the authoritative core of its learned academies, has declared seriousness an anachronistic state of mind. In biblical times, a covenant signified primarily a pact between man and God, a usage of the term that connotes (besides the utmost seriousness) fidelity, solemnity, and primordial truth. In this sense of the word, one can find oneself party to a covenant without voluntarily entering into it; indeed, one is born into the agreement made by one’s ancestors, and in the covenant between man and God, the ancestors happen to be the entire human race, going back to its earliest presence in the world. As modernity has finally succeeded in removing religion to the peripheral regions of society, it is quite beyond the power of most people to imagine what such an agreement might amount to. What would be the concrete obligations or the visible parties involved? If we were to take the American Constitution as a candidate for a covenant in the ancient sense, one could object that not only does one enter into it voluntarily, but its fundamental principles are nowhere near universal, much as some would like them to be so.

If we look, however, to our everyday communication through speech, we could make an argument that grammar itself is a covenant. Without the laws of speech, how could we enter into any agreement, even one as trivial as trusting a stranger to give us directions in a foreign city? We know that, for ancient societies, even a small error in the arrangement of words could be a harbinger of discord in the spiritual bonds that made those societies strong and enduring. But it has been many years since the rules of grammar have been binding in our speech, and we have put no new rules in their place, seeming rather to be satisfied with temporary conventions of signs that emerge from and disappear back into a nondescript mass of isolated words, commercial pictographs, musical snippets, bodily gestures, and nonverbal sounds.

Is truth itself a covenant? Alas, in the academy, truth along with seriousness has been brought in for questioning and is now being held, awaiting trial. But let us consider truth anyway, for it offers the best hope in the modern age of rediscovering a primordial sense of covenant. Our choice for where we must look for truth as a covenant will be another of the liberal arts—logic, which, if it is to be practiced at all, must presuppose not only the ancient preoccupation with metaphysical truth but also the seriousness and existential fidelity of a covenant between language itself and the world. Unlike grammar, which can be used indifferently and still be recognizable, the case of logic is an either-or situation: in making a claim to say something is necessarily true and valid, one’s speech is either logical or not. Try as one might, one cannot get around this. But it is, I would claim, the old logic’s1 stubborn loyalty to ordering human thought in its desire to know the essential natures of things that has allowed it to transcend its nature as a liberal art and become a guardian of the truth of human relations with the world and with God.

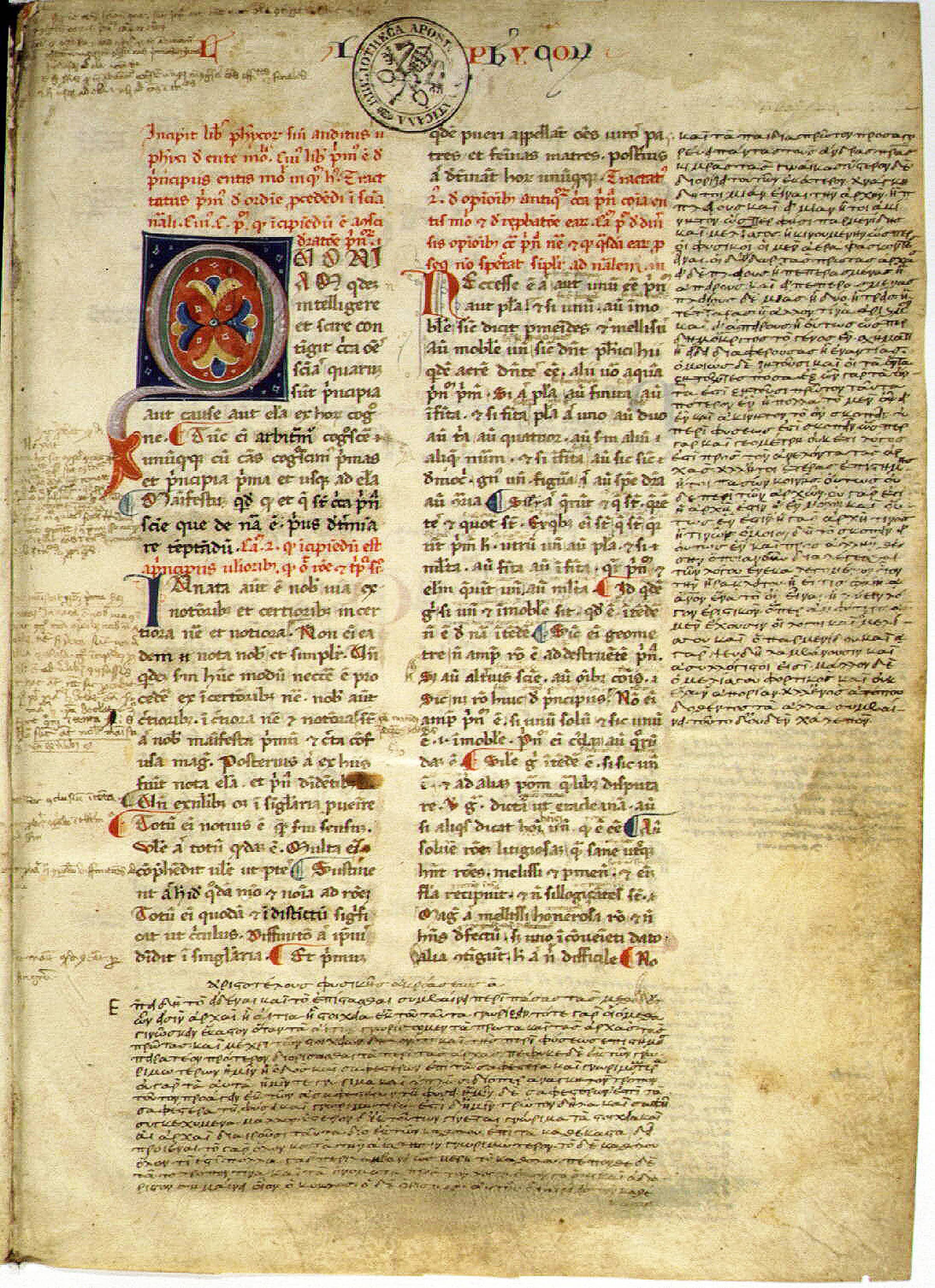

The beginning of Physics (Aristotle). Medieval Latin manuscript with the original Greek text added in the margins

Further, traditional logic oriented its theory and practice around several levels of truth, beginning with a relation of truth in which all human beings must participate, namely, the simple intuition of the common natures or “kinds” of things; then proceeding to the truth of logical propositions, which, because they are voluntary covenants, can just as well end up being false; and finally, arriving at the truth of the syllogism, which, because it must be accompanied by validity, is even less likely to achieve the soundness of necessary truth. If practiced well, though, logic can reveal these levels of truth in their development in the human intellect, as it were, from seed to sapling to tree, ending, one must hope, in the flower of wisdom. As we shall see, although the last level was thought to be the perfection of the human intellect, it was the first, intuition, that guaranteed that the relations involved in it could justifiably be called “covenants,” for, as the ancients believed, though reasoning marks the essence of humanity, intuition is divine. Throughout my account I will appeal primarily to the writings of Thomas Aquinas as medieval scholasticism’s most precise and eloquent witness to logic’s “covenants of truth.”

In his Disputed Questions on Truth, Thomas Aquinas quotes figures from Latin, Islamic, and Jewish traditions who have given metaphysical definitions of truth that bear on the primordial connection between human and divine knowledge. The first definitions by St. Augustine and Avicenna refer to “ontological truth”—that is, the truth of “being” itself—which the intellect grasps, albeit “through a glass darkly,” in the first operation of logic: the intellect’s simple apprehension of a thing’s2 essence.

Truth or the true has been defined in three ways. First of all, it is defined according to that which precedes truth and is the basis of truth. This is why Augustine writes: “The true is that which is”; and Avicenna: “The truth of each thing is a property of the act of being which has been established for it.” Still others say: “The true is the undividedness of the act of existence from that which is.”3

These definitions place truth at the heart of reality, of universal being itself. The being of things precedes and is the condition of their truth; moreover, for St. Augustine, the being of things is derived from God directly by an act of creation, which is not merely the fact of a thing’s coming-to-be but the establishment of a relation between it and the Creator. Indeed, because a thing can neither maintain nor bring itself into existence, the relation must be permanent. As a “property,” truth always brings with it a relation, and the particular nature of the relation will always involve knowledge.

And this is what the true adds to being, namely, the conformity or equation of thing and intellect.4

However, whereas things correspond to the human intellect as the measure of its knowledge (the human intellect is true insofar as it conforms to the things it wishes to know), they correspond to the divine intellect as the measured to the measure (a thing is true insofar as it is known by the divine intellect). This twofold relation of truth, though neglected in modern treatments of medieval metaphysics, is in fact necessary to account not only for the existence of the intelligible forms of things but also for their capacity to make themselves known to the human intellect—as well as to the cognitive powers of all other animals.

A natural thing, therefore, being placed between two intellects [the divine and the human] is called true in so far as it conforms to either. It is said to be true with respect to its conformity with the divine intellect in so far as it fulfills the end to which it was ordained by the divine intellect…. In a natural thing, truth is found especially in the first, rather than in the second, sense; for its reference to the divine intellect comes before its reference to a human intellect. Even if there were no human intellects, things could be said to be true because of their relation to the divine intellect.5

Truth, therefore, is present from the beginning in a thing’s existence as a creature, a product of God’s creative will and knowledge.6 And it is coextensive with being, for anything that is has been created by God and, in being created, is established in a relation of truth to the divine essence. On the one hand, the first truth, establishing as it does the possibility of human knowledge, can be said not to be human at all:

Truth is primarily in a thing because of its relation to the divine intellect, not to the human intellect, because it is related to the divine intellect as to its cause.7

On the other hand, Aquinas conceived of truth as being transmitted to the intellect and acting upon it through the medium of created forms.

By its form a thing existing outside the soul imitates the art of the divine intellect; and, by the same form, it is such that it can bring about a true apprehension in the human intellect.8(emphasis mine)

The intellect, then, can only achieve the conformity of truth with things because they have already been established in a relation of truth with their Creator.

So far, we have been speaking of a divine truth that resides in created beings themselves, such that they can be called true merely by virtue of their act of existing and, through that act, their being able to transmit that truth to the human intellect. No casual inference from the belief that the Creator is Truth itself, this “ontological truth” signifies a real agreement with God on the part of things. In this context, every simple intuition of a thing’s nature speaks of the intellect’s desire to enter into a covenant of truth with it; this covenant is as much with God as it is with the thing, for the truth that the mind encounters is the thing’s correspondence with Him. Now, because things existed in the divine knowledge before they were created, it follows that they also conformed to the divine intellect—they were true—before they were created. Moreover, once a thing is created, its relation of conformity to God is created as well— an uncreated covenant begets a created covenant. By being thought by God, the creature becomes a potency for being thought by a created intellect, from whence it follows that the mechanism by which the human intellect is made true depends entirely on the divine knowledge. Mystical theologians describe the transference of divine form to the intellect through created beings as a transference of lights: in being made by the Father of lights, things themselves become lights for the illumination of minds. Our covenant with other creatures, therefore, is a covenant with the Creator.

Aquinas believed that the idea is the intellect’s internal response to the thing: once the intellect intuits a thing’s essential nature, and because it is produced spontaneously upon the intellect’s spiritual contact with things, the idea is, as it were, the seal of a covenant of truth that acknowledges the intellect’s kinship with things and, remotely, its kinship with the divine essence. Indeed, for the human intellect to function at all according to its nature, it must grasp the universal essences of things apart from the things themselves. If we could not understand the essence of, for example, “cat” apart from the particular characteristics that make up individual cats, we would not be capable of reasoning, since all reasoning depends upon the capacity of the intellect to grasp many individuals under a common nature, or species.

Mystical theologians describe the transference of divine form to the intellect through created beings as a transference of lights.

The human being knows in various ways, beginning by sensing things that are immediately present: one encounters a bird in a tree and is able to describe its individual characteristics—its color, size, shape, the particular song it makes. When the bird flies away, one can preserve an image of it in one’s imagination and change it by adding other characteristics that do not naturally belong to the bird—one can make it breathe fire or have a lion’s head. If one has a healthy imagination, one can almost see the absent bird as it really appeared when it was present and being seen. But no matter whether one changes the image in the imagination or recalls it as it was seen, the sensible image will always be bound up with the thing itself. From whence it follows that, if sense images were all we possessed, we would only be able to think of individual things and never know their common natures.9 The small bluebird we saw yesterday afternoon and the large crow we saw this morning could never be thought as “bird.” But to know the latter is to know birds not according to the senses or the imagination but according to the intellect. Intuitively, unreflectively, immediately, by the natural intelligibility of things, the intellect lifts the individual beyond the material limits of its individuality by begetting an idea that alone can signify the common nature they share. Indeed, the intellect can only know “this” as “this kind of thing”—that is, as the idea of its species. (It knows everything literally as “one of a kind.”) The special power of the idea is, therefore, to bring individuals into the spiritual unity of their kind, and because of this, it participates in the most primordial of all covenants:

And the earth brought forth grass, and herb yielding seed after his kind, and the tree yielding fruit, whose seed was in itself, after his kind: and God saw that it was good.… And God made the beast of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind: and God saw that it was good.10

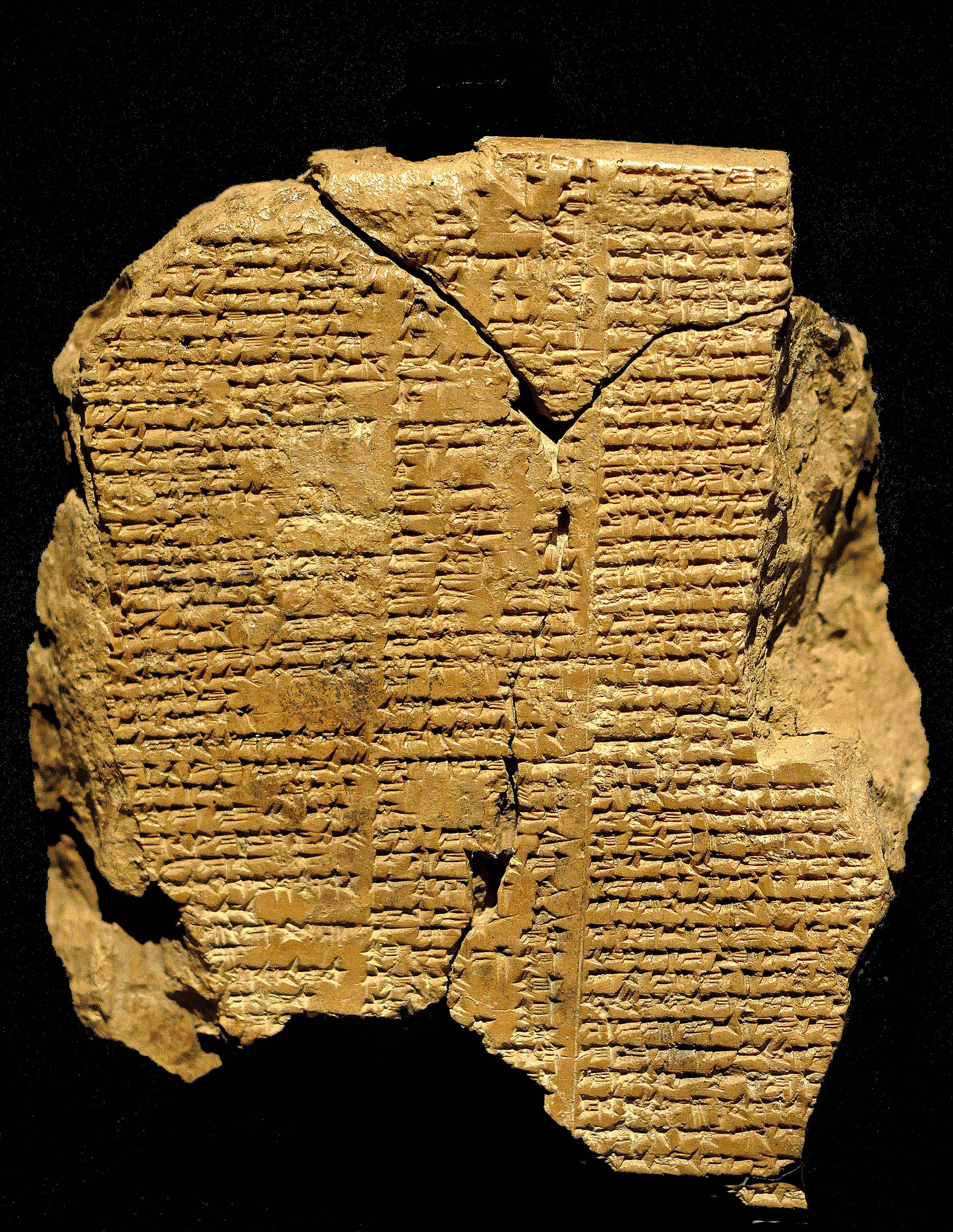

Partially broken Tablet V of the Epic of Gilgamesh; old Babylonian period, 2003–1595 BCE

What is logical about all this? Whereas the science of metaphysics takes as its object the very being of things, logic looks exclusively to the laws of their being known. For example, one knows that this individual is a human being, but in the same act of knowing, logic recognizes the universal nature, “human being,” as a species, which signifies that the individual is subordinated in a relation of universality to that nature. It is logic, moreover, that discovers that the kinds of things are themselves ordered according to higher degrees of universality, for the intellect naturally knows the many species as a genus (“cat” and “horse” as “animal”), and the many genera as a higher genus (“animal” and “plant” as “living thing”). Besides the covenant it makes with the individual, then, the intellect makes other covenants that bind things together in ever greater bonds of commonality. But since all of these relations derive their conformity with reality through the intellect’s immediate intuition of the individual, even the concept of “being” can only be thought because one being has already been thought. Thus, moving from the truth of the simplest covenant, that between the intellect and a single being, the intellect brings to light the commonality of the covenant itself—namely, that it is binding for all beings. In knowing the truth of being, it knows virtually all the covenants of being, and in all of them it finds the same covenant: that things are created according to kind.