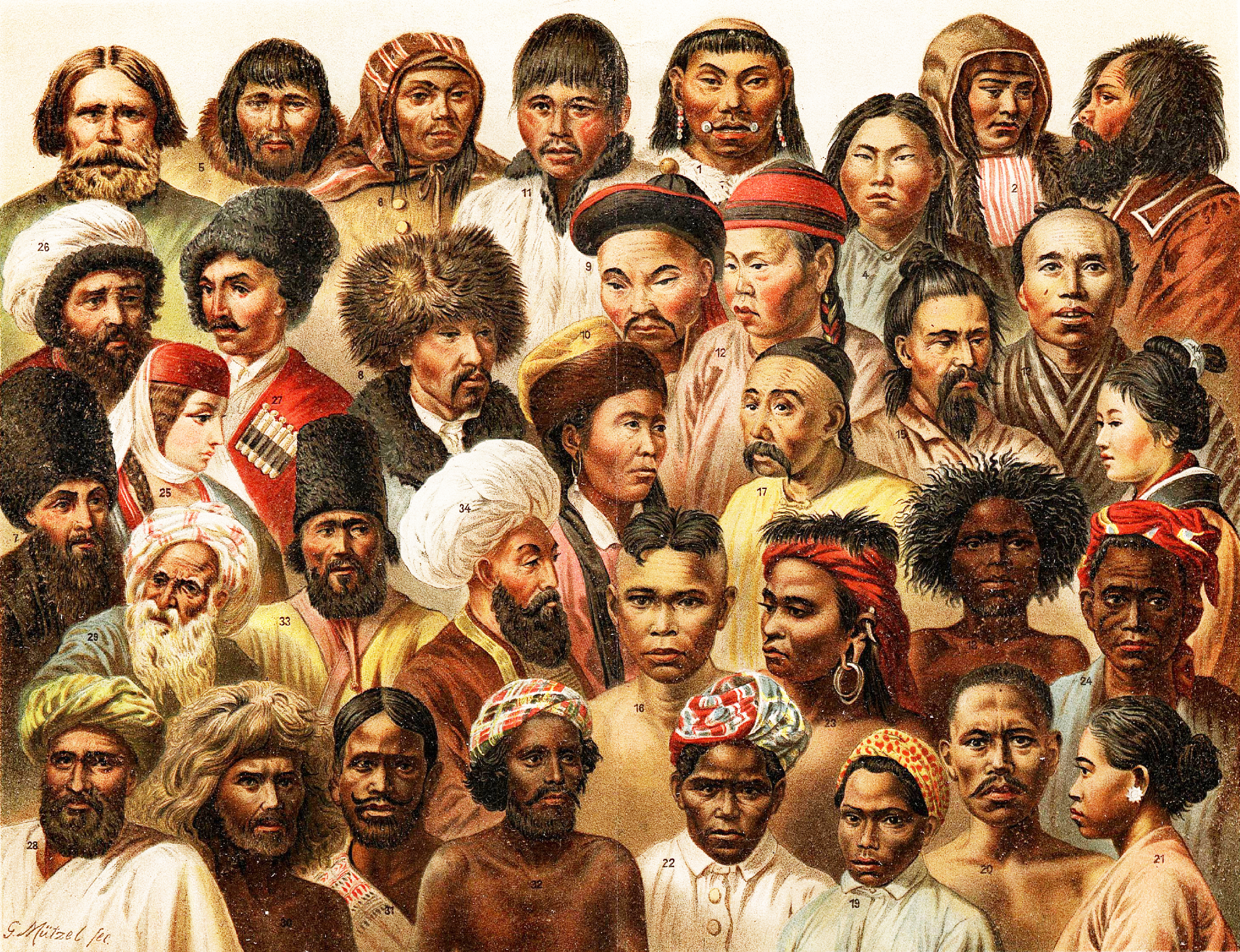

This image was first published in the Nordisk familjebok in 1904: Wikimedia Commons

The long struggle in the United States for racial equality, which has thrown up memorable and impassioned phrases, such as “We shall overcome,” “I have a dream,” and “Black lives matter,” has sought procedural equality for minorities, who systematically have been treated differently from the white majority by police. In this light, it has struck me that the Qur’an is remarkably uninterested in any distinction between the self and the barbarian, or between white and black.

The world of late antiquity, to which the Qur’an was preached, was on the whole hostile to the idea of equality. The rise from the fourth century of a Christian Roman Empire under the successors of Constantine did nothing to change the old Greek and Roman discourse about civilized citizens and “barbarians.”1 In Iran’s Sasanian Empire, Zoroastrian thinkers and officials made a firm distinction between “Iran” and “not-Iran” (anīrān), and there was no doubt for Sasanian authors that being Iranian was superior in every way.

Podcast: Equality in the Ancient World with Juan Cole and Ubaydullah Evans

Still, these civilizations at the same time transmitted wisdom about human unity. Socrates cheekily pointed out that pretenders to the robes of Greek nobility had countless ancestors, including the indigent, slaves, and barbarians as well as Greeks and royalty (Theaetetus 175a). Zoroastrian myth asserted that all mankind had a single origin in the primal man, Gayomart.

The Qur’an was recited by the Prophet Muĥammad in the early seventh century, on the West Arabian frontier of both the Eastern Roman Empire and Sasanian Iran. In Arabian society of that period, one sort of inequality was based on appearance and on a heritage of slavery. Children of Arab men and slave women from Axum (in what is now Ethiopia) remained slaves and were not acknowledged by their fathers. Those who became poets were called the “crows of the Arabs.”2

Some sorts of hierarchy are recognized in the Qur’an, but they are not social or ethnic. Rather, they are spiritual. In late antiquity, those who argued for equality did not necessarily challenge concrete social hierarchies but rather concentrated on principle and on the next life.3 For Islam, as for Christianity, it is ethical and moral acts of the will that establish the better and worse (though the Qur’an does urge manumission of slaves as a good deed and promulgates a generally egalitarian ethos). The Qur’anic chapter of Prostration (32:18) says, “Is the believer like one who is debauched? They are not equal.” The two are not on the same plane, not because of the estate into which they were born or because one is from a civilized people and the other a barbarian but because of the choices they have made in life. In short, this kind of inequality is actually an argument for equality. The Chambers (49:13) observes, “The noblest of you in the sight of God is the most pious of you.” This is a theme to which we will return.

Reading the Qur’an requires attention to what scholars of literature call “voice.” It switches among speakers with no punctuation or transition. Sometimes the omniscient voice of God speaks, but sometimes the Prophet does, and sometimes angels do or even the damned in hell. In chapter 80 (He Frowned), the voice of God addresses the Prophet Muĥammad personally, using the second-person singular. The passage is a rare rebuke of the Messenger of God by the one who dispatched him. In my translation, I have used small caps for the pronouns referring to Muĥammad. Initially, the divine narrates Muĥammad’s actions in the third person, but then God speaks directly to His envoy about delivering the scripture, here called “the reminder”:

1 HE frowned and turned away,

2 because the blind man came to HIM.

3 How could YOU know? Perhaps he would purify himself,

4 or is able to take a lesson, and so would benefit from the reminder.

5 As for those who think themselves self-sufficient,

6 YOU are attentive to them;

7 but YOU are not responsible if they will not purify themselves.

8 As for those who come to YOU, full of earnest striving

9 and devout,

10 YOU ignore them.

The great historian and Qur’an commentator Muĥammad b. Jarīr al-Ţabarī (d. 923) quoted the Prophet’s third wife, ¢Ā’ishah, on the significance of this passage. She said, “‘He Frowned’ was revealed concerning Ibn Umm Maktūm. He came to the Messenger of God and began to say, ‘Guide me.’ The Messenger of God was with pagan notables. The Prophet began to turn away from him, addressing someone else. The man asked [plaintively], ‘Do you see any harm in what I say?’ He replied, ‘No.’” Despite his being blind, ¢Abd Allāh b. Umm Maktūm was later made a caller to prayer in the Medina period, according to another saying of ¢Ā’ishah. The man’s name underlines his marginality in Arabian society of that time. He is the son (Ibn) of “the mother (Umm) of Maktūm (his older brother).” Arabian names were patriarchal like those of the Norse, for instance “Erik Thorsson.” It was an embarrassment to lack a patronymic, to be defined only by one’s mother’s name. The blind ¢Abd Allāh b. Umm Maktūm would have been named with regard to his father if anyone had known who the latter was. Thus, he was a person of no social consequence in the small shrine city of Mecca.

The plain sense of these verses is clear, whether this anecdote is historical or not. The Prophet is scolded by the voice of the divine for having turned his back, annoyed, when the blind nobody dared make a demand on his time and attention. What is worse, ¢Abd Allāh did so while Muĥammad was giving his attention instead to a gathering of the wealthy Meccan elite—those who thought they were “self-sufficient” and did not need God’s grace. The voice of the divine points out that Ibn Umm Maktūm’s soul was just as valuable as the souls of the pagan magnates, and it was possible that, with some pastoral care, he might accept the truth. The Prophet Muĥammad preached, according to the later Muslim tradition, from 610 to 632, and this incident is thought to have occurred early in his ministry. Was it 613? It is implied in the Qur’an that God intervened right at the beginning of Muĥammad’s career to underscore that the mission work had to proceed on the basis of the spiritual equality of all potential hearers.

Skin color was used in many ways by authors in the ancient world and not always as a sign of inferiority or superiority, but there were undeniably forms where discrimination played a part. When the widely read Greek medical thinker Galen at one point described “Ethiopians,” he mentioned their outward attributes, such as frizzy hair and broad noses, but then went on to describe them also as mentally deficient.4 Solomon’s bride in the “Song of Songs” describes herself as black: “I am black and beautiful, O daughters of Jerusalem, like the tents of Kedar, like the curtains of Solomon.” This description caused late antique Christian authors some puzzlement, since they did not associate blackness with beauty or other positive attributes.5 The ancient world did not have a conception of race, a modern idea that emerged in its contemporary sense in the nineteenth century; it only had a set of aesthetic preferences around appearances. But some authors clearly did invest blackness with negative connotations.