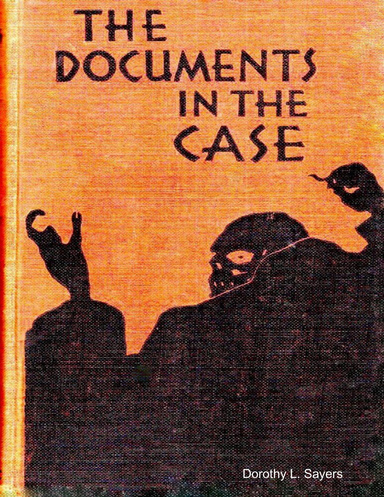

Book cover, The Documents in the Case, Dorothy Sayers

I am reduced to complete pulp by Bishop Talbot, who says that in FOUR talks devoted to Why we want a God to believe in, it has not occurred to him to explain what is meant by the word ‘Sin’!!!!! You wouldn’t think anybody could overlook that theological trifle, would you?

—Dorothy L. Sayers 1

Quick, versatile, and ever ready to embrace a challenge, Dorothy Sayers (1893–1957) had a diverse career arc. She began by publishing poetry and translating medieval romances, such as The Song of Roland, and ended as a recognized and respected Christian apologist, essayist, dramatist, and ambitious translator of Dante’s The Divine Comedy. She also worked in advertising as a copywriter for nearly a decade, from 1922 to 1931, and it was during this time that she began to write detective fiction. Until 1934, nearly all of her published work was related to this genre.

Sayers wrote her detective fiction during the Golden Age of detection and crime writing, which roughly spanned the interwar period, from 1913 to 1937. Like many of her contemporaries in the genre, she didn’t concern herself with her contributions alone, nor only with the fictional. She edited a total of five short detective fiction anthologies, collecting the cream of nineteenth- and twentieth-century suspense, and wrote many reviews of detective fiction.2 She was a founding member of London’s celebrated Detection Club and in 1949 became its third president (G. K. Chesterton and Agatha Christie were also presidents in its history). Like many of its members, she made the understanding of real cases her concern, such as when she explored the unsolved 1931 murder of Julia Wallace for the collection The Anatomy of Murder (1936).3

But one novel in particular, The Documents in the Case (1930)—the only one of nearly a dozen detective novels that doesn’t feature Lord Peter Wimsey, her famous amateur sleuth—best demonstrates how Sayers always invigorated her detective fiction with an underlying, but no less important, activity of detection for readers. This is evident in the multiple, at times conflicting, points of view this book offers as it moves between various documents written by its cast of characters; the myopia of the human condition comes to the fore as the reader recognizes and considers the gaps and spaces between perspectives—and their moral implications for the self and others both on and off the page. None of Sayers’s novels are meant to be pure entertainment or escape, nor a way to instill a false sense of safety or achievement in the reader, glad to know the murderer is caught in the end (and perhaps patting herself on the back for twigging the trail of clues and correctly guessing the guilty party before the big reveal). No. Sayers resisted this form of easy amusement; she not only wanted us to spot the murderer but also intended us to spot the Seven Deadly Sins.

Sayers possessed deep knowledge about the Sins, both through her upbringing as the only child of an Anglican rector and through her early academic interest in medievalism and Christianity. Her familiarity with the moralizing methods of medieval texts meant she regularly came across colorful, Hieronymus Bosch–esque illustrations of the Sins, like the depiction of Lust as a reckless porcupine attempting to gather apples on his quills, chasing a lost one, and ending by losing them all; or the image of Envy as so self-destructive that, when a man is told he can have whatever he wants with the understanding that a second man will have double what he requests, it motivates him to ask for the removal of one of his eyes.4

More than ten years after publishing The Documents in the Case, on October 23, 1941, Sayers delivered an address to the Public Morality Council at Caxton Hall in Westminster entitled “The Other Six Deadly Sins.”5 It was her first express examination of the Seven Deadly Sins after years of embedding them in her literary work, and she pointedly, with characteristic dry wit, closes the address with a condensed reprise of them, “just in case there is anybody who[…] has not the list at his fingertips.”6 Sayers levies her address at the Church—that is, at “you and I”—and specifically raises the issue of laxity: the laxity of church members in sufficiently identifying and countering all Seven Deadly Sins, as opposed to the hard work she sees church members putting into minimizing, or simply omitting, six of the Sins while overemphasizing Lust.7

In the address, Sayers personifies the Sins, painting their portraits within the frameworks of modern-day social behaviors. She wants to make visible the very real, deep-seated, and insidious nature of each Sin, how cunningly they shape-shift from age to age in their efforts to become Accepted Practice. Covetousness, rebranded as “Enterprise” in the twentieth century, swaggers and swashbuckles like the rake, eschewing all responsibility for the fallout of his actions. Wrath is the “mischief-maker” and, when he appears as righteous anger, becomes an “ugly form of possession,” one which we do not always see for what it is because it deftly “cloaks itself under a zeal for efficiency or a lofty resolution to expose scandals.”8 Gluttony is contextualized within the modern economy’s “vicious circle of production and consumption,” which incites the public’s “greedy hankering after goods which they do not really need.”9 Pride is “the sin of the noble mind” with the “devilish strategy” of “attack[ing] us, not on our weak points, but on our strong.”10 Sloth, meanwhile, is the “empty heart and the empty brain and the empty soul […] persuad[ing] us that stupidity is not our sin, but our misfortune.”11 Avarice, a form of Covetousness, is called “the sin of the Haves against the Have-nots.” Envy is “the sin of the Have-nots against the Haves.”12

At every turn, Sayers boxes in her listeners. If you think you are free from the Seven Deadly Sins, think again. If you think your position as either poor or rich, man or woman, curate or layman, married or single somehow saves you from the worst the Sins have in their arsenal, then watch out.