Sep 16, 2025

The Readiness of the Soul

Emilio Alzueta is the vice dean of the College of Languages in Motril (Granada, Spain).

More About this Author

Emilio Alzueta is the vice dean of the College of Languages in Motril (Granada, Spain).

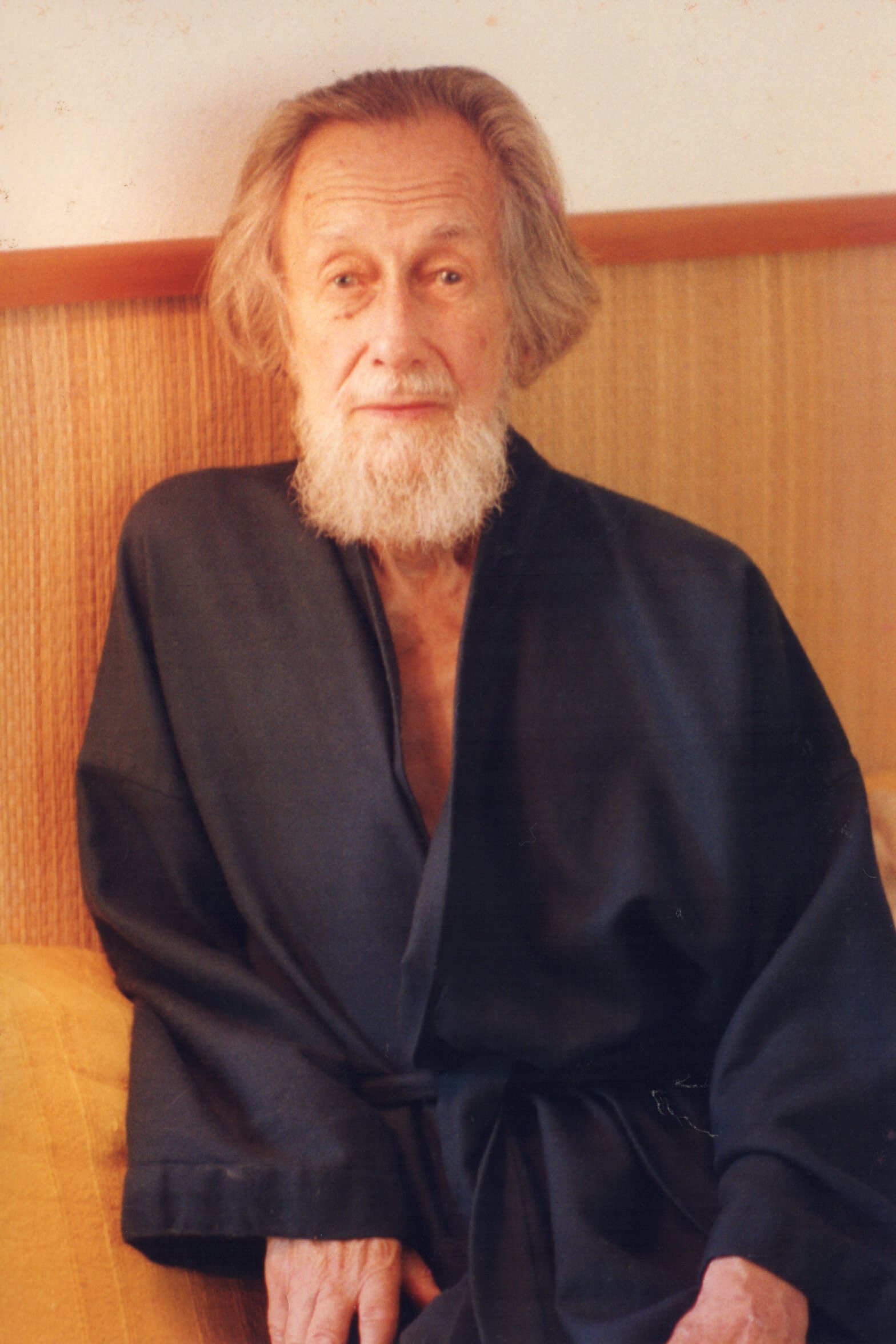

More About this AuthorMartin Lings (d. 2005) is widely known as a scholar of Sufism and Shakespearean literature, as well as the author of a celebrated biography of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ in beautiful high English prose.1 Less familiar, however, is Lings the poet, although his consummate mastery of language permeates all his works.

His Collected Poems is a slender but intense volume.2 It is divided into two sections: his early poems—written in the 1920s, when he was at Oxford University and a student of C. S. Lewis—and his late poems, written from the 1950s onward.3 Despite their separation of more than twenty years, the two sections have a remarkable unity of form and meaning. It was perhaps due to his choice of topics and his classical diction, so removed from the contemporary poetic scene, and to the scarcity of his output that Lings never became recognized as a significant poet in the canonical English literary tradition. Yet his work is certainly worthy of attention, and it contains some pieces—such as the extraordinary “Meeting Place”—that should be part of any true anthology of twentieth-century English verse.

Lings’s Collected Poems includes eight exquisite sonnets, six belonging to his early poems and two to his later ones.4 In employing the sonnet, Lings is choosing one of the most distinguished and enduring poetic forms in Western poetry, one that has proven capable of attracting poets throughout history and in many languages and of conveying a seemingly inexhaustible range of themes. As Christopher Kleinhenz, the distinguished scholar of Italian literature, said, “For centuries, the sonnet has remained the most popular and the most difficult poetic form in Western literature.”5

Though its centrality to the Western literary tradition cannot be overemphasized, the formative period of the sonnet may surprise us with some profound cultural intermarriage. The sonnet—from the Italian sonetto, or “little song”—was reputedly created in Sicily in the first part of the thirteenth century. The first example that is preserved was written by Giacomo Lentini at some point between 1233 and 1240. The first quatrain places the sonnet in the orbit of courtly love, in which it would quickly find its maturity:

Amore è uno desio che ven da’ core

per abondanza di gran piacimento;

e li occhi in prima generan l’amore

e lo core li dà nutricamento.

Love is a yearning that comes from the heart

Through the abundance of so much delight.

It is the eyes that first give birth to love

And the heart that provides its nourishment.6

Lentini was the chancellor in the cosmopolitan and highly Arabized court of the king of Sicily (later Holy Roman emperor) Frederick II, and it was around this multifaceted Norman king that “the last flowering of the Provençal tradition” took place.7

During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the troubadours in the Provençal language—one of the first vernacular offshoots of Latin—had been singing their love songs in the courts of southern France, northern Italy, and northern Spain. Their poetry would center on the theme of courtly love, in which the lady held dominion over the poet, almost like a feudal lord over his vassal. The literary circle in Sicily would adapt the troubadour themes and style into the vernacular language of southern Italy, developing the new form of the sonnet. According to André Ughetto:

It then existed in the island… a popular song that the Italians called strambotto, and that in the Sicilian variant was known as ottava.… Those eight verses of regular measure already consisted of a doubling of quatrains with similar rhymes: abab abab. It (then) became a habit to precede or follow the ottava with a sestina (six lines).8

From Sicily, the sonnet then traveled to Tuscany and the school of the dolce stil novo (sweet new style) of Cavalcanti and Dante. In his La Vita Nuova (The New Life), Dante traces the amatory-spiritual experience of his love and loss of the angelic Beatrice (later rediscovered in her heavenly aspect in the Divine Comedy) in prose interspersed with delicate and poignant sonnets. It was, however, the humanist Francesco Petrarca who—in his Canzoniere—gave the sonnet its definite model, after which it would extend to all major European languages.

What is remarkable is that each of those first three steps in the formation of the sonnet, before its definitive Petrarchan coinage, corresponded to a literary movement that was influenced by Arab poetry and Islamic literature and spirituality. The songs of the Provençal troubadours were largely an offshoot of the Arabic love song, which came into southern France from the high culture of Al-Andalus. One of the great cultural attractions of Spanish cities at the time were the qiyān, or young women singers, who had a repertoire of songs on the subject of courtly love. María Rosa Menocal records how Duke William IX of Aquitaine, one of the first troubadours, took a group of these singing women to his court after the Norman conquest of Barbastro, in the north of Spain.9 In fact, according to some literary critics and historians, the very word troubadour could have come from the Arabic word ţaraba, “to sing” (although some scholars believe it has its origin in the Latin trovare, “to find or invent”).

Furthermore, Frederick II—around whom the Sicilian school flourished—knew Arabic and liked to surround himself with Muslim scholars. He also founded one of the first universities in Europe (the medical school in Naples) on the model of Islamic universities, and he promoted the translation into Latin of great Arabic scientific texts, such as the Canon of Medicine by Ibn Sīnā, continuing the tradition of the Toledo School of Translators in Spain. As stated by Samar Attar, “The formation of Italian literary texts between 1200 and 1400 cannot adequately be understood without reference to the various Arabic and Islamic sources that date back to the seventh century onward.”10 The very invention first of the ottava and then of the sonnet in Sicily might have been indebted to the structures of Arabic poetry, at a time when the romance languages first evolved from Latin. Kamal Abu-Deeb writes that the sonnet has “schemes, or structures, that are variations… on structures of the muwashshahat produced by Arab poets.”11 Ughetto also discusses the possible influence of the Andalusian zajal and the Arabic ghazal on the sonnet, not only from the point of view of the form itself but also on account of the existence of cycles of ghazals, which could have influenced the birth of the great Italian sonnet cycles.12

Finally, Dante—the main exponent of the Tuscan school of the dolce stil novo and one of the towering figures of Western literature—was also very probably influenced by various spiritual and philosophical aspects of Islam.13 As Miguel Asín Palacios noted as early as 1919, Dante’s masterpiece, the Divine Comedy, draws from medieval translations of texts on the Prophet Muhammad’s mi‘rāj, or miraculous Night Journey and Ascension to heaven.14 Moreover, the Fedele d’Amore (Love’s Faithful), an esoteric group to which Dante belonged, not only rested on the tenets of Neoplatonism and Christianity but was arguably influenced by Islamic spirituality. Ibn ‘Arabī’s poetry for his beloved Niżām, perceived as a theophanic locus (tajallī) of the Divine, precedes Dante’s portrayal of his Beatrice, who becomes a manifestation of heavenly grace.

This historical excursus is not a mere digression but a way to deepen our understanding of what Lings is doing in his sonnets. He is a Muslim poet who is steeped in both the Western and the Islamic traditions and who uses a form that is both quintessentially Western and historically indebted to Islam, showing the illusion of the impermeability of these two traditions. Moreover, he writes about ideas that have largely been lost in the contemporary Western world, reinvigorating Western literature from the living tradition of Islam, and about ideas that are profoundly relevant to both Muslims and non-Muslims—in fact, to any human being. We will find the fuller import of this in the discussion that follows.

Among Lings's sonnets, one of his later pieces stands out for its extraordinary pregnancy of meaning: “Readiness.” It is a Petrarchan sonnet, which Chiara Sibona calls a “bi-logical” form—with an antithesis between the content of the octave and the sestet—in contrast with the “tri-logical” Shakespearean sonnet.15 In both its forms, the sonnet is a highly sophisticated and concentrated literary model that—in the space of fourteen lines—combines the metaphorical and emotional intensity of lyricism and human drama with the syllogistic possibilities of formal logic and the procedures of rhetoric.

The poem goes as follows:

Half souls, scarce differing, each his difference frantic to stress!

Unheard of themes, trite themers—O, for the opposite!

Banish whatever is but was not, only admit

What was and is and shall be; but, the old to express,

Be new thyself, by being thyself, and being no less.

The soul fulfilled is new, unique; own every bit

Of thine, have power, when truth comes, to assent to it

Utterly, therefore uniquely: such is readiness.

Then, only then, upon the sea of verse unmoor

Thy vessel, and spread these new-found sails in plenitude.

Let them be white, or black for sorrow or as rich mood

Of soul may dye them, plain or patterned with sacred Lore.

Let them be worthy that the Wind its breath may pour

Into their fullness, to spirit thee from shore to shore.

A first reading of the sonnet easily reveals that the word “readiness” is not only the title but a sort of pivot in its formal unfolding, given special relevance by its position at the very end of the octave. Understanding its full meaning is thus a good place to start. Webster’s Dictionary registers the following meanings:

1. Quickness; promptness; promptitude; facility; freedom from hindrance or obstruction.

2. Promptitude; cheerfulness; willingness; alacrity; freedom from reluctance.

3. A state of preparation; fitness of condition.

Readiness—the state or quality of being ready—can therefore mean not just preparation or willingness, the most common meanings in modern English, but also a wholehearted and cheerful disposition or acceptance, an inner freedom to give oneself entirely. That is, for example, the sense of the word in Acts 17:11, in the King James Bible: “They received the word with all readiness of mind”—that is, giving themselves to it without inner obstruction.

Martin Lings

Textually, the poem “Readiness” can be said to gravitate around that pivotal word. Its middle position, just at the end of the octave, connects it both to the beginning of the poem—“Half souls”—and to its end—“from shore to shore”—establishing a sort of tension line:

Half souls ------------- Readiness ------------- [Then, only then] from shore to shore

The dynamic relationship among these terms—underlined by the poem’s division into octave and sestet—brings out the basic or root meaning of the poem, which can be expressed as the transformative undertaking of two consequent steps. The first step—in the octave—consists of the soul’s transformation from a fragmented “half soul” to a soul that has reached the state of readiness. The second—in the sestet—consists of the soul’s inspired traveling “from shore to shore,” which can only take place (“then, only then”) after it has reached the state of readiness.

The first step is made up of strife and purification, and, consequently, the discursive structure of the octave—with its intricate dialectics and syncopated lines—underlines the tension between opposites. The essence of that tension is the paradoxical contrast between the old and the new, between tradition and innovation, between being an imitator and truly being oneself. The second step, however, is made up of inspiration and aesthetic or spiritual movement, which is underlined by more fluent and lyrical poetic discourse.

Lings starts the sonnet with two somewhat cryptic lines, which can be said to encapsulate the condition of modern man:

Half souls, scarce differing, each his difference frantic to stress!

Unheard of themes, trite themers—O, for the opposite!

Modern man is obsessed with what we could call the “superstition of originality.” For him, to be successful in the human project means to affirm his own personality, his particular way of thinking, feeling, and behaving. For Lings, however, this obsessive—“frantic”—affirmation comes, as it were, from the periphery of our selves. If we are not integrated and do not have real access to the most profound dimensions of our being, to what we truly are, we are only “half souls.”16 We simply identify with our ego-self (nafs) and body, and with the most mechanistic and worldly aspects of reason (‘aql), but we have —if at all—only dim and intermittent access to our spiritual heart (qalb) and spirit (rūĥ).

However, in paradoxical contrast with modern man’s strong urge for individuality, modern civilization is very much a civilization of uniformity. Increasingly, the West has imposed over the world a monoculture—from habits of conduct to architectural styles—that has undermined the cultural variety of the world. There is a crucial difference between unity and uniformity. The first is the manifestation of the One in diversity, and it is expressed in harmony; the second is only a parody of unity and, ultimately, a sort of denial of the One. The paradox is that despite their obsession with originality, modern men are “scarce differing,” increasingly identical and governed by power dynamics designed to control man as an isolated consumer. He may believe that he is more and more free to think and behave, but both his thinking and behavior are increasingly conditioned, distorted, and surveilled. As the French philosopher Gustave Thibon once said, there is no prison more effective than one with invisible bars.

Another “superstition” characteristic of modernity is novelty. Modern man compulsively looks for new ideas, new topics, new forms—often feeling that it is their very novelty that makes them worthy, not paying attention to whether they are true, or conducive to the truth. Indeed, they become for him a kind of addiction, given the postmodern conditioning that truth not only cannot be found but does not even exist. Modern man searches for “unheard of themes,” but he lives in the periphery of his being and follows the dictates of the ego-self and an increasingly superficial culture: he is a “trite themer.” Lings, however, yearns for the opposite:

Banish whatever is but was not, only admit

What was and is and shall be; but, the old to express,

Be new thyself, by being thyself, and being no less.

Lings yearns for a condition in which we can express the same eternally true themes, but can do so from the very core of our being. In order to do so, we have to realize and actualize our full nature, to live and speak and create from our center, our purified spiritual heart, and from a transformed, mature self. True intellection, true realization (taĥqīq), comes from the complete, purified being; as Plotinus said, “Never can the eye see the sun unless it had first become sunlike, and never can the soul have vision of the First Beauty unless itself be beautiful.”17 This implies a transformation that is also a renewal. When man becomes a real human being, when he regains the Adamic archetype that lies at his core, then his soul becomes new and unique:

The soul fulfilled is new, unique; own every bit

Of thine, have power, when truth comes, to assent to it

Utterly, therefore uniquely: such is readiness.

We are left, then—as so often in the realm of the spirit—with a paradox. Our attempts to stress our difference, to search for superficial novelty, to live and talk from our ego-selves, unexpectedly lead to uniformity and triteness. However, as we “move inwardly” and progress from difference to inner unification, real uniqueness is manifested.

There are profound metaphysical implications here. Though we live in the world of diversity, in the infinitely changing manifestation of the One—and, therefore, all human beings are truly different—this diversity is not chaotic but harmonious and based on archetypes. Harmony and principially anchored diversity are the necessary expressions of unity. While God’s absolute and incomparable unity (aĥadiyyah) means that nothing at all is like Him (Qur’an 42:11), God’s principial unity (wāĥidiyyah) gives rise to multiplicity as its ultimate first principle and deepest unifying reality. It manifests in the fact that none of His creations are fully alike—not two leaves from the same tree, not two bees from the same beehive—but also in the harmony that permeates that diversity and in the fact that all individual bees correspond to the same archetype of the bee. Though no two fingers have the same print, all fingers are alike; though no two personalities are the same, all human personalities follow the same basic pattern. Difference and unity, permanence and variation, have to be affirmed in the proper dimension, in the proper manner, and with the proper courtesy.18

The inner realization that Lings proposes, then, takes us from the fragmented and peripheral areas of our being to an inner transformation that allows us to assent to the truth and progress in the gradual realization of the truth. This is the genuine manifestation of “readiness” of the spirit. “Then, only then” can the inspired traveling of the sestet take place:

Then, only then, upon the sea of verse unmoor

Thy vessel, and spread these new-found sails in plenitude.

Let them be white, or black for sorrow or as rich mood

Of soul may dye them, plain or patterned with sacred Lore.

Let them be worthy that the Wind its breath may pour

Into their fullness, to spirit thee from shore to shore.

The sails symbolize the spiritual aspiration and knowledge that arise when we come into our true selves. The sails—the spiritual heart—not only acquire different spiritual coloring but become the tablet in which wisdom—“sacred Lore”—is inscribed, a knowledge that is not acquired (kasbī) but granted (wahbī). Sincere and wholehearted assent to the truth makes the heart worthy of and receptive to the wind of inspiration so that the human being can fulfill the journey from the shore of this physical world of harmonic multiplicity to the shore of ultimate Unity, Beauty, and Perfection.

On the aesthetic and literary level, the relationship between tradition and original personal expression has often been a subject in literary criticism. Tradition, in this sense, is not just the historical collection of works in a particular language or of a particular civilization but something more, the organization of that collection into a concrete but not immutable canon, which remains always relevant to the present. T. S. Eliot, in his classic essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” famously summed up this conception in the framework of Western literature:

[Tradition] involves, in the first place, the historical sense… and the historical sense involves a perception not only of the pastness of the past but of its presence; the historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer, and within it the whole of literature of his own country, has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order.19

In all civilizations, and even in Western history up to the nineteenth century, literature and art were largely produced against the background of that traditional canon, which served as a model and a criterion. It was commonly understood that an artist had to imitate and master traditional forms until he was able to make a truly worthy individual contribution. Imitation, in this sense, although it could sometimes become stifling, was generally seen not as negative or as precluding measured innovation but as a way to aspire—especially in the presence of real talent—to the level of the great beacons of the past. Imitation also provided the artist with a discipline and a shared code that would make his new contribution truly valuable and sufficiently universal. This was even more acutely so in the Islamic world, in which the literary and artistic canon was governed by principles and forms that were part of a wider revelatory and religious tradition, while in the West, that tradition had started to unravel at least since the Renaissance.20 Not until modern times did an emphasis on individual authorship, as is now prevalent in the West, start to circulate in the Islamic world.

The whole point of Eliot’s conception is balance. The way in which the strict rules of the sonnet stimulate personal inspiration—as so many poets have experienced—reminds us of the fact that setting limits, both by adhering to a particular form and by imitating models and examples, fosters creativity rather than precluding it. Moreover, the examples of the great masters of the past help us to extract what is true and valuable from ourselves.

In “Readiness” we find a poignant longing for this balance. Lings invites the artist or the writer to embody tradition and its norms as a way—only superficially paradoxical—to be truly original. In fact, the word original comes from the Latin origo, originis (origin): we are really original inasmuch as we reconnect ourselves with the origin of things. Similarly, the Arabic word mubdi‘, which comes from the root bā’, dāl, and ‘ayn and is sometimes used in classical Arabic to refer to a great artist, is a reflection of one of the names of Allah, al-Badī‘, the One who unceasingly creates new creatures, never repeating Himself.21 What Lings says is that true originality and innovation have to be searched for in the depths of our soul, not in our immature ego-self and our caprice (hawā). That inner depth will also shine on the self, but it will do so from the eternal truths of “what was and is and shall be,” renovated in each true poet by the imperative of “being thyself, and being no less.”

The traditional conception of art, both in the Islamic and in other civilizations, underlined three necessary requisites or steps, which we can call imitation, expression, and effusion.22 The first, imitation, is not only connected with the relationship between the individual artist and tradition but also with the imitation of nature—not of its objects but of its operation. The word poiesis in Greek means “making” and “creating,” but it also refers to the “coming forth” (aleteia) in nature: art imitates the operation of nature and can also reflect the higher imaginal and spiritual worlds, which shine through in nature.23

The second requisite, expression, points to the inner presence of heart and intellect in the work, in all stages of practice, as well as to the paradoxical ability of “the soul fulfilled, new, unique.” In this regard, the exquisite essayist Simon Leys has said, in the context of a discussion about Chinese calligraphy:

“There is a crucial difference between unity and uniformity. The first is the manifestation of the One in diversity, and it is expressed in harmony; the second is only a parody of unity and, ultimately, a sort of denial of the One.”

The great performers [of music] erase themselves as much as possible in order to serve their models; but the more they are successful in this task, the more deeply their individual sensibilities and temperaments are revealed in their performances.… Throughout the centuries, in the East and the West, the great mystics that attained the erasing of the self were at the same time the most original and vigorous personalities. In the art of calligraphy, as in spiritual life, self-expression reaches its peak when the negation of oneself is complete.24

Expression also includes the process of inner transformation that the artist’s craft provides, which is, in turn, a requisite to its refinement. Virtue cannot be separated from beauty because it is, in fact, a form of even higher beauty, a connection that the Arabic language—with its metaphysical character—indicates in the words ĥusn (beauty, virtue) and iĥsān (excellence). In this regard, Diotima says in Plato’s Symposium:

Some men are pregnant in respect to their bodies.… Others are pregnant in respect to their soul—for there are those… who are still more fertile in their soul than in their bodies with what pertains to soul to conceive and bear. What then so pertains? Practical wisdom and the rest of virtue—of which, indeed, all the poets are procreators.25

Finally, the third step is effusion, the epiphany of the transcendent in the immanent, the gleaming of the manifestation (tajalliyyāt) of the divine names and the spiritual archetypes in this world of matter—which is also, in its own right, a realm of shining. It is the music that sounds through the reed flute when the artist has been purified, the knots opened up, all courtesies observed; a music that, like the wind, is ultimately not played, but gifted.26

The sestet of “Readiness” movingly describes the artistic accomplishment that arises from the equilibrium between tradition and true originality, which assumes the presence of imitation, expression, and effusion. The waters that the poet’s art (the “vessel”) navigates are a “sea of verse” because they have the potentially oceanic quality of language or music. The sails—already in their plenitude of craftsmanship—acquire the variegated colors with which the spiritual realm dyes the world and the human being. The poet unveils the light, the meaning, of this vast universe of signs (āyāt) that we inhabit. In Arabic, shi‘r (poetry) comes from the root sha‘ara, “to feel” but also “to perceive, to understand.” To be a real poet, then, is to decipher those signs by pointing to the truly signified; it is to show the connection between the symbols of this world and their celestial archetypes. When the artist’s sails are in a state of readiness, they may be blown into their fullness by angelic inspiration, taking the poet—like the castaway Ferdinand in Shakespeare’s The Tempest—to the Miranda of love and higher

meaning.

Gradually turning inward, we get to the third level of interpretation: the spiritual reading. This is, in fact, the most difficult level to write about because genuine spirituality can and at the same time cannot be expressed in words. This elusive quality was marked in the classical Islamic spiritual discourse by the distinction between ‘ibārah and ishārah. While the first refers to the outer, evident signification, the second could be translated as “allusion,” a subtle or symbolic meaning. The great Sufi scholars were supreme practitioners of ishārah, as this was required by the spiritual nature of their language and the reality it pointed to. But in a minor key, it could be said that true poetry always partakes in some measure of this power of allusion.

According to some Sufi scholars, at the root of the spiritual path we find a double journey, first toward the purification of our heart—our spiritual center—and then, from that center, toward the truth. That double path—first horizontal, then vertical—has its archetype in the Night Journey and the Ascension of the Noble Prophet ﷺ, which took him from Mecca to Jerusalem and from that holy city to the presence of his Lord, after traversing the seven heavens.

Not until we reach the fullness of the spiritual heart and the stability of the tranquil self (al-nafs al-muţma’innah) can we truly start that spiritual ascension. Ömer Tuğrul İnançer al-Halveti al-Jerrahi, a great contemporary Sufi authority from Turkey, said that the path of taśawwuf (Sufism, Islamic spirituality) does not consist in losing oneself but in finding oneself.27 That is, the path is about refining the ego-self, the nafs, so that it can become a lantern for our true self, which is the mirror where the divine theophanies (tajalliyyāt) manifest.

In our conscience, the nafs constantly claims to be our true and complete self, and it presents to us an illusion of capricious individuality and autonomy. The process by which the nafs is governed and refined and by which we are centered in our spiritual heart is based in Islam on following the Noble Qur’an and the prophetic way, or sunnah, as well as becoming a disciple to a perfected spiritual master connected to the Prophet ﷺ by a continuous line of transmission, or silsilah. Such a master can guide the aspirant (murīd) through the steps of sacred law (shariah), spiritual path (ţarīqah), truth of spiritual states (ĥaqīqah), and inner, direct knowledge of the truth (ma‘rifah). The paradox—much in line with the other paradoxes expressed by the poem—is that our true uniqueness lies not in our personality but in our center, and this center is the realm of the Prophet’s light and the prophetic example. As the Qur’an says, “[The Prophet] is closer to the believers than their selves [anfus]” (33:6). Therefore, by giving up our childish notions of personal uniqueness and embracing the inner and outer sunnah, we are transformed from a “trite themer” to “a fulfilled soul, new and unique.” The concept has been beautifully illustrated by Charles Le Gai Eaton:

“Sincere and wholehearted assent to the truth makes the heart worthy of and receptive to the wind of inspiration.”

At first sight one might expect [following the sunnah] to produce a tedious uniformity. All the evidence indicates that it does nothing of the kind; and anyone who has had close contact with good and pious Muslims will know that, although they live within a shared pattern of belief and behaviour, they are often more sharply differentiated one from another than are profane people, their character stronger and their individualities more clearly delineated.… The great virtues—and it is the Prophet’s virtues that the believer strives to imitate—can, it seems, be expressed through human nature in countless different ways, whereas worldly fashion induces uniformity. In media advertisements one “fashion model” looks very much like another.28

The purification of the heart unveils the virtue of spiritual poverty (faqr), the existential recognition of the servant’s absolute need of his Lord. The masters say that when the soul “assents to truth utterly,” when the heart is made ready by spiritual poverty and sincerity and sustained by the remembrance of God, the human being can start the real journey, with the luminous guidance of a spiritual master. The first journey was traveling by land; the second is a voyage by sea—in the ocean of the ‘ālam al-malakūt (angelic realm, the world of lights).29 The Noble Qur’an says:

Among His Signs are the tall ships, sailing like mountains through the sea. If He wills, He makes the wind stop blowing and then they lie motionless on its back. Certainly in this are Signs for everyone who is steadfast and thankful. (42:32–33)

Just as, in the times of old, sailing ships could only move because of the wind’s force, the spiritual sea voyage is made through the breath of that holy wind. In its course, the sails will be dyed with the colors of the soul, “as rich mood of soul may dye them, plain or patterned with sacred Lore.” These are the spiritual states (aĥwāl), which color the heart, and the spiritual stations (maqāmāt) in the path, like gifts or stages in the voyage to the shore of realization.30

The two steps that, separated by the isthmus of the state of readiness, make up the textual substance of the poem are finally, here, in this spiritual level of interpretation, clarified in their fullest sense. In the words of Maĥmūd al-Shabistarī, one of the greatest Sufi poets of all time:

The journey of the Pilgrim is two steps and no more.

One is transcending beyond selfhood

And the other is toward nearness with the Beloved.31

In “Readiness,” Martin Lings uses the concentration and polyvalence characteristic of great poetry to express ideas, symbols, and experiences that resonate in the realms of philosophy, aesthetics, and spirituality. This concentration is aided by the very form of the sonnet: a literary artifact perfected by generations of masters and capable of fruitful conciseness, a treasure chest of meaning, which is also a small mirror able to reflect the cosmos and its counterpart, the human being. As Dante Gabriel Rossetti famously wrote, “A sonnet is a coin; its face reveals / The soul.”32

The fact that Lings writes in both the Islamic and the Western traditions illustrates how both strands are historically intertwined, and how what is truly traditional is always subject to rooted and authorized renewal. Yet whatever the density of meaning of the text, and its fascinating ramifications, we should remember that “Readiness” is a poem and that poetry is very different from prose. Lings could have tried to say the same thing by means of an essay—and indeed he has developed some of these ideas in his books—but the medium of poetry joins concepts, subtle allusions, symbols, emotions, sensory impressions, and musical rhythm and melody into an aesthetic object that affects us differently than other kinds of text. As the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset said, poetry criticism and exegesis should start and end with the poem itself, rather than trying to be a substitute for it.33 A personal, immediate reading and appreciation of “Readiness” should both precede and conclude this essay. Or not quite, because—like all Sufi poets—Lings didn’t write this poem as a mere literary exercise but as an inspiration, a reminder, and an aid in the path.

The beginning, then, is reading, but the end is reflection, action, and transformation.

An abbreviated version of this Text Message appeared in the Spring 2025 print edition of Renovatio.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy