Podcast: Why Beauty Is Not Optional with Oludamini Ogunnaike

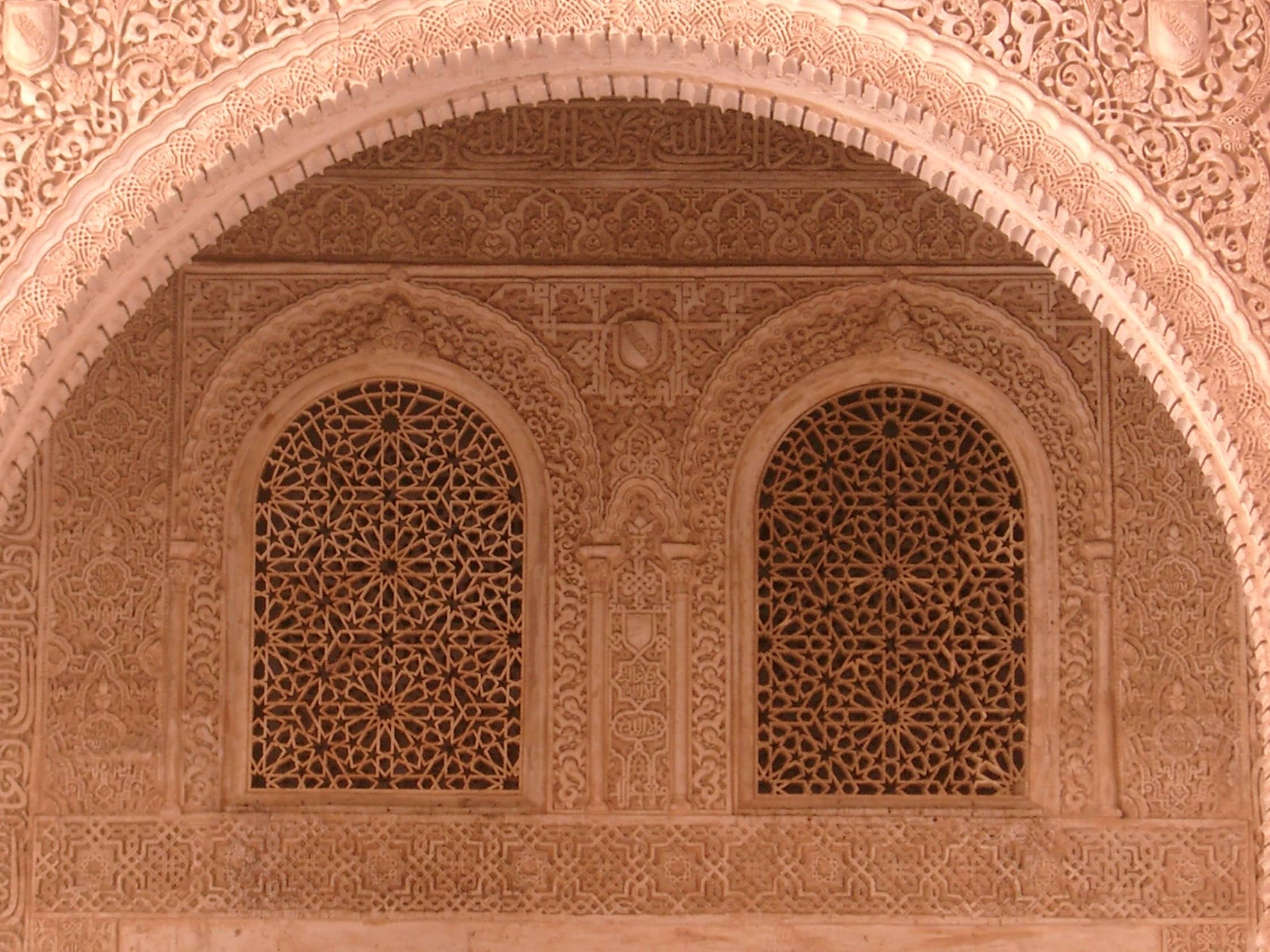

Detail from the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain

As such, the beauty of Islamic art attracts love, both human and divine. Whether praying in or even just strolling through the beautiful mosques of Istanbul or Isfahan, one cannot help but feel love and beloved, regardless of the circumstances outside. This gentle presence of beauty and love causes the sakīnah—the deep peace engendered by the awareness of the presence of God—that is one of the most characteristic features of the architecture of all traditional mosques. The harmony of their geometry makes the barakah (sacred presence) of the space tangible, helping to bring our souls into balance.

Turning to the literary arts, the Islamic civilization’s obsession with love can be found in verses of love poetry scattered in Islamic treatises of logic, law, geometry, theology, and philosophy. Until recently, the culture of love permeated nearly all of the traditional Islamic literary genres and understandings of reality. For scientist-philosophers, such as Ibn Sīnā, love was quite literally the force that moved everything in the cosmos, from rocks to angels.

Moreover, love is essential to the cultivation of iĥsān and the closely related concept of ikhlāś (sincerity). As a hadith says, “None of you truly believes until God and His Messenger are more beloved to him than anything else.” Without this selfless love, our pious actions and worship are motivated either by pretentious arrogance (riyā’), which the Prophet ﷺ called the lesser or hidden shirk (idolatry, setting up a partner alongside God), or by a selfish desire for rewards or to escape from punishment in this life or the next, instead of by loving God for His own sake and loving others for His sake, as well.11 Either way, this limits our love and enslaves us to our own selves and desires: “Have you seen him who has taken his desire to be his god? God has led him astray” (45:23), “but those who believe are more intense in love for God” (2:165). To paraphrase a verse by the poet Hafez, “apart from lovers, all I see is self-righteous hypocrisy.” The Qur’an directs the Prophet ﷺ to give love as the reason and reward for following him: “Say: if you love God, then follow me and God will love you” (3:31).

Love always attaches itself to beauty of one kind or another. When mosques and places of learning are beautiful, we are drawn to them. When speech is beautiful, we are drawn to it. Beauty inspires love, and love moves our souls.

Love is the truest and most sincere motivation for any action; it is what moves our souls in one direction instead of another. Love always attaches itself to beauty of one kind or another. When mosques and places of learning are beautiful, we are drawn to them. When speech is beautiful, we are drawn to it. Beauty inspires love, and love moves our souls. This is true for supra-sensible divine beauty, which the Islamic arts try to make sensible, but unfortunately it is also true for the gaudy, shallow “beauty” of shopping malls, skyscrapers, and the “adornments of this world” (zīnat al-ĥayāh al-dunyā, Qur’an 18:46), which are really a parody or a shadow of true beauty. This begs the question of the difference between the liberating beauty of Islamic art and the distracting, hypnotizing “beauty” of the dunyā. How can one discern between the two, and why is it important to do so?

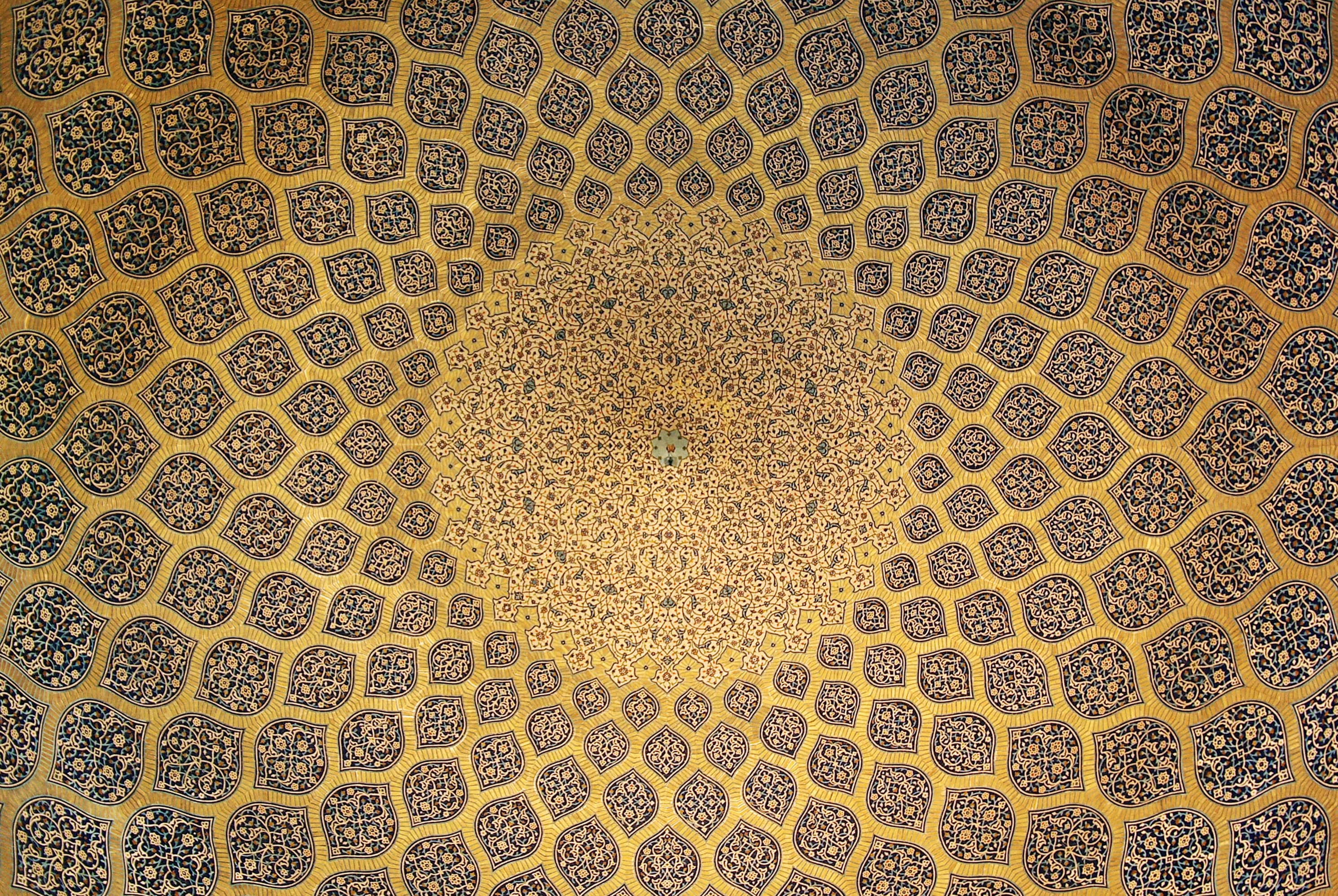

In order to distinguish Islamic art from other forms of art, we must define and demarcate Islamic art. Although Western art historians were slow to recognize the unity of the Islamic arts in cultural regions as different as West Africa and Central Asia, scholars such as Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Titus Burckhardt have compellingly made the case for a universal Islamic approach to the arts that manifests itself in different variations in different local contexts. In doing so, these scholars have helpfully distinguished Islamic art from Muslim religious art and from art made by Muslims. The form and content of traditional Islamic art springs directly from the Qur’anic revelation and diffuses the perfume of the Muhammadan blessing (barakah Muĥammadiyyah).12 The Islamic arts incorporated the techniques and methods of Roman, West African, Byzantine, Sassanid, Central Asian, and Chinese artists to give birth to a new art depicting the new religion’s vision of reality. The true source of Islamic art is the Islamic revelation, not its historical precedents or influences. This singular origin accounts for its remarkable unity across time and space.

Art made by Muslims or even art made in Muslim societies is not necessarily Islamic art. The late Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid designed many famous buildings, but none are examples of Islamic architecture. Conversely, students of all faiths at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts in London produce works of traditional Islamic calligraphy, illumination, and geometric design. It is the form of the art, shaped by revelation and not the identity of the artist, that makes a work distinctively Islamic.

As these epigrams suggest, the Islamic arts are gates through which we can access the deepest truths of the cosmos, the revelation, and ourselves. The neglect of these arts is a terrible blow, not only to our aesthetics but also to our ethical, intellectual, and spiritual lives. Just as our bodies, in a sense, become what we eat, our souls become what we look at, listen to, read, and think about. When the Islamic arts are rare, unrecognized, and underappreciated, what then happens to our souls?

Just as our bodies, in a sense, become what we eat, our souls become what we look at, listen to, read, and think about. When the Islamic arts are rare, unrecognized, and underappreciated, what then happens to our souls?

The loss of the Islamic arts is also deeply connected with the rise of extreme sectarianism, the atrophy of the imaginal faculty, and the overall difficulty perceiving unity in diversity. In traditional Islamic cosmology and metaphysics, multiplicity and difference govern the outward world of appearances, whereas unity increases the farther one travels inward, into the world of meaning and spirit. Because God is one, as one approaches the divine presence, things become more unified. Those without access to this unity are unable to perceive and participate in the harmony—the reflection of unity in multiplicity—that links the world of appearances to that of realities. Imagination and the arts are bridges that unite these two worlds.

Podcast: The Silent Theology of Islamic Art with Oludamini Ogunnaike

Dome interior of Shaykh Lutfollah Mosque

Those with a deep appreciation of the Islamic arts can appreciate the barakah of and identify the profound realities represented in the architecture of Almohad Morocco, Mamluk Egypt, or Safavid Iran completely irrespective of the official legal school or theology of these dynasties. Moreover, those familiar with the profound principles of Islamic art cannot help but notice these same principles, albeit in a different mode, in the sacred arts of the other revealed religions. Islamic art, like Islam itself, synthesizes and confirms the traditions of sacred arts that came before it.17 Anyone familiar with the theory and principles of Islamic music cannot help but admire Bach, and those adept in adab will find much to appreciate in the works of Shakespeare and Chuang Tzu, despite the great differences in the way the Muslim composer and these authors applied universal principles. In addition, anyone familiar with Islamic sacred geometry cannot fail to recognize the same principles at work in Buddhist and Hindu mandalas and temples.

This is precisely what Muslim scholars and artists have done for generations: understood, appreciated, and integrated the arts and sciences of other civilizations. One of the clearest signs of our decline has been the virtual disappearance of these synthetic and creative intellectual and artistic processes. This has also been accompanied by increasing tensions between different Muslim groups and minority communities of other faiths that thrived in Muslim-majority lands for centuries. The Qur’an describes the diversity of humanity as providential and divinely willed in order for us to know one another, and through this knowledge, to better know ourselves and our God.18 As Muslims lose touch with knowledge of our arts, of our history, of ourselves, of our tradition, and of God, we lose touch with reality and with the ability to recognize the truth and humanity of those who differ from us.19

For Muslims who practice a craft, such as the Islamic arts of calligraphy, poetry, or Qur’anic recitation, that craft provides them with a model for Islamic spirituality. A craft is an activity that requires continuous practice and improvement over a lifetime, not a cookie-cutter mold into which one either fits or does not. If we view the purification of our hearts, the attempt to follow in the Prophet’s footsteps, and the quest to know God as a craft or an art form instead of as an identity, we can understand how different approaches can lead to the same or a similar goal. Thus, I believe the recent epidemic of takfīr could be ameliorated by understanding the practice of Islam as an art form instead of focusing on an either/or notion of Muslim identity.

All is not lost, however. Discernment, whether intellectual or aesthetic, is difficult to recover once lost, but the Qur’an says, “Ask the people of dhikr, if you do not know” (21:07). Those Islamic societies and communities with thriving traditions of Islamic spirituality tend to have thriving artistic traditions, even if they are not economically wealthy (as in West Africa). This is because the practice of Islamic spirituality, being the science of taste (dhawq), refines one’s taste, enabling recognition of spiritual truths and realities (ĥaqā’iq) in sensible forms; similarly, the Islamic arts support and refine the practice of Islamic spirituality. The revival of the arts must be a priority for Muslims worldwide because the arts are vital to the rejuvenation of the Muslim mind and soul.20 As Plato wrote, “The arts shall care for the bodies and souls of your people.” While many have attempted to reduce the Islamic tradition to a list of dos and don’ts in the realm of behavior and belief, the Islamic arts serve as a powerful reminder of the more profound realities of the tradition, of iĥsān, and of the purpose of the entire Islamic tradition in the first place: the highest art of bringing the human soul back to its fiţrah, which perfectly reflects all of the divine names and qualities, both the jalāl (the majestic) and the jamāl (the beautiful).

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy