I have not made them witness the creation of the heavens and the earth, nor their own creation.

QUR’AN 18:51

History, if viewed as a repository for more than anecdote or chronology, could produce a decisive transformation in the image of science by which we are now possessed.

THOMAS KUHN

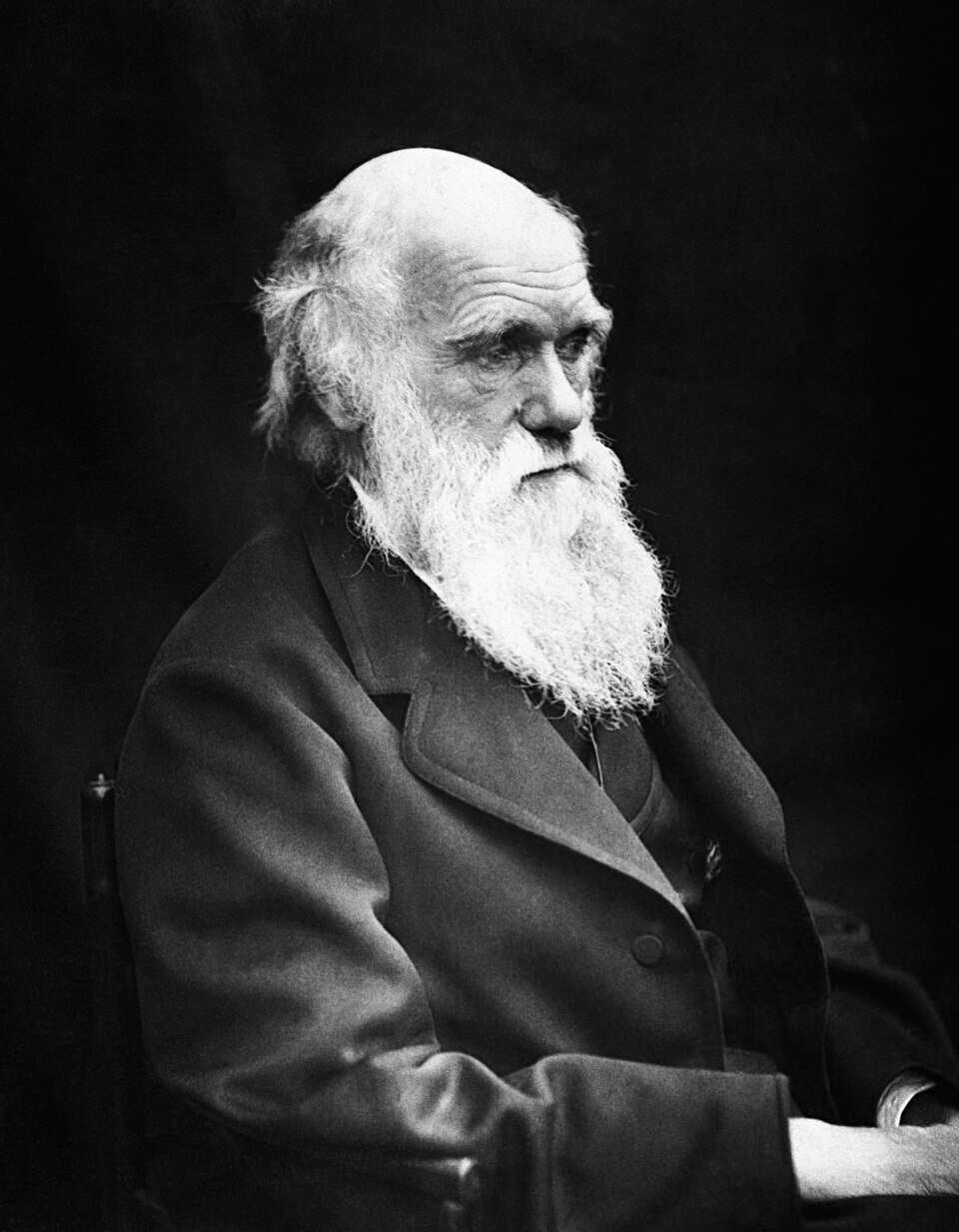

Charles Darwin, 1869

Think “Charles Darwin” or feed the name into a search engine and there turns up a mild-mannered, heavy-bearded, elderly gentleman in a three-piece suit. The man we see, typically cast in sepia or gray tones, broadcasts sagacity. We might as well be staring at the Victorian incarnation of a Greek philosopher. No paraphernalia, no backdrop—no context—situates him. Few have ever met a younger Darwin or would recognize him if they did. An elementary school or literary encounter might portray him “as a naïve, innocent, school-boyish, outdoor, nature-loving traveller and collector, whose theories emerged from lucky meetings of his genius with exceptional observational opportunities.”1 This is the familiar Darwin: a lone naturalist, stripped of all historical contingency, circumstances, social networks, and influences.

Of course, much of this popular perception is entirely true. Darwin was endowed with great observational skills, a remarkable ability to synthesize vast amounts of evidence from diverse disciplines, and an unimpeachable dedication to his calling. He was an obsessive collector and scribe, carefully annotating samples and documenting discoveries and information gathered from biologists, botanists, geologists, pigeon fanciers, horse breeders, zookeepers, and others.

That said, much is missing from this picture.

Evolution by natural selection is a Victorian scientific theory that has come to occupy a standard place in biology. The reading public might know the theory in its repackaged form as “the modern synthesis”—roughly, Darwinian selection plus Mendelian genetics. Turn back the clock, however, and the scientific landscape looks quite different. In the nineteenth century, there were numerous evolutionary theories. Philosophies of nature competed within a modernizing world, amid divergent political interests; the English and European scientific scene was lively and dramatic. There were no neatly circumscribed intellectual territories that separated scientific activities from philosophical introspection. Titles like “scientist” were just entering public discourse; efforts to carve out a scientific profession were just beginning. The one naturalist whose name would survive this formative period and eclipse all others, at least in our shared historical consciousness, is Charles Darwin (d. 1882).

A twenty-first-century reader of Darwin’s magnum opus, On the Origin of Species (1859), might be surprised if not disappointed at its lack of scientific tone and its style of analysis. By today’s norms, Origin reads somewhere between intimate correspondence and a formal travel account. Its language aimed to persuade through description and by tying together evidence from a host of disciplines—geology, botany, population studies, and other fields. In fact, Darwin intended the book as “one long argument” and “an abstract” for a proper scientific manuscript that never came to life.2 Darwin would revise his “argument” in six editions published over thirteen years, with the phrase “survival of the fittest” only appearing in the fifth edition and the word “evolution” only in the last. The former coinage was not even Darwin’s; it was introduced by Herbert Spencer (d. 1903). Indeed, many hands went into the production of Origin and its central theory: the principle of natural selection. This concept was, and still is, at the heart of controversies over biological evolution. Biologist and vocal atheist Richard Dawkins has described natural selection as a “masterpiece” and glorified its “explanatory power.”3 Yet Darwin never gave a straightforward definition of natural selection and could not even convince his inner circle (of evolutionists!) of its so-called explanatory power.

Evolution remains a recurring topic of discussion—online, in the workplace, and over dinner—between theists and atheists representing various strains of creationism and evolutionism. As in the nineteenth century, there are no neat categories: a conservative Muslim might indiscriminately subscribe to the theory of evolution over here, while an atheist over there might scoff at natural selection. But for all the furor, enthusiasts and opponents of evolution alike (including biologists on either side) tend to be ill informed about its history and deeper philosophical enigmas. This lack of awareness is usually coupled with confusion about how science works and what it can and cannot tell us about reality.

Studying the history and philosophy of science can help dispel ignorance about evolution and science more broadly. The case of Darwin is an occasion to test our beliefs about “science,” to humanize its pioneers, and to show that many of the questions they grappled with still haunt us today despite decades or even centuries of empirical research. Examining present controversies often shows that they repeat old debates, considering unresolved puzzles may bring to the fore early differences of opinion and untrodden paths, and studying naturalists and their theories in context can reveal hidden assumptions and philosophical biases. Therefore, probing evolution’s philosophical arguments in light of its history is a useful complement to both theological and scientific inquiry.4 Historical and philosophical knowledge helps us to be informed, granular, and selective about our commitments—in other words, it equips us to ask critical questions and to interrogate mere conjecture and scientist encroachments on metaphysical matters beyond the scope of science. And there is no better place to start than with the “Devil’s chaplain,” as Darwin once jokingly labeled himself.5

As talented as Darwin was, he did not arrive at his concepts through pure and simple scientific insight. Darwin made sense of nature and inferred its inner workings through the prisms of his circumstances and of contemporary thought. It is tempting to think of naturalists as dispassionate, objective individuals to whom the absolute truth is revealed thanks to sheer intellectual prowess.6 In reality, Darwin intertwined his interpretation of nature with questions like whether or not one could legitimately speak of progress, and to what extent did God intervene in creation, with his answers often tainted by subjective premises he inherited from his world. Darwin sojourned in dynamic places in a revolutionary period, among engaged thinkers and activists, surrounded by ideas embodied in the concrete materiality of the fast-mechanizing and expanding British Empire. His work, too, was situated in the thick of this cultural matrix. Victorian society; Britain’s industrial preeminence, global aspirations, and self-perception in a colonial era; racialized visions of humanity; class struggle; gender differences; the political debates and currents of the day; and personal experiences all shaped Darwin, his beliefs, and the very content of his theories. One of his leading biographers, Janet Browne, says it like this: “Darwinism was made by Darwin and Victorian society.”7

An uncomplicated image of Darwin might cast him as the objective scientist who arrived at his breakthroughs via plain observation and experimentation. In this simplistic portrait, evolution has no prehistory and no context. This conceals the facts that evolution itself has evolved and that its origins and ingredients matter decisively in how we talk about the theory today. A careful examination of Darwin’s writing alongside the books he read, the people he met and learned from, the sociopolitical issues of his time, and his correspondences makes it clear that Darwinian evolution can be neither described as “just science” nor understood independently from its historical setting. Studying Darwin up close is both an opportunity to gain a critical awareness of metaphysical and theological assumptions that are present in his formulation of evolution—and which have nothing to do with empirical science proper—and an invitation to adopt a more sophisticated view of science in general.

Darwin may be the poster child of evolution, but he did not invent the idea. The Victorian era was full of efforts to construct worldviews on an evolutionary foundation.8 By the time Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, a handful of evolutionist doctrines were already in wide circulation, and many of the themes he addressed were new neither to him nor to his readers. Historians are therefore reluctant to speak of a “Darwinian revolution”—at least not without serious caveats.9 French Enlightenment authors like the philosopher Denis Diderot (d. 1784) and the naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (d. 1788), advocated developmental ideas in the eighteenth century.10 Darwin’s own grandfather Erasmus (d. 1802) entertained the possibilities of common ancestry and divergence among animals in the late 1780s and 1790s. By the first decade of the 1800s, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (d. 1829)—who coined the term biology—had proposed a theory of evolution by the inheritance of acquired characteristics—transformisme, he called it. The naturalist speculated that animals could transform their bodies gradually and heritably by force of will or habit. This theory was defended and extended by another prominent French zoologist, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (d. 1844), whose morphological views slowly aligned with Lamarckian transformism following a four-year expedition in Egypt, where he served as a savant in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army.

Lamarckism and Geoffroyism crossed the English Channel and were disseminated in the penny press. The notion that an animal could change itself into a higher being through its own efforts and pass on the gains to its progeny appealed to the working class and radical physicians. In 1826, zoologist Robert Grant (d. 1874), who studied with Saint-Hilaire and taught Darwin in Edinburgh, became the first in Britain to talk of animals having evolved, in the sense of transmuting from one species into another (until that time, evolution had referred to embryological development). Eventually came the best-selling Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), a Victorian sensation by Scottish thinker Robert Chambers that brought transmutation off the streets and out of medical theaters and into the English home.11 Finally, Alfred Russel Wallace (d. 1913) independently identified a principle close to Darwin’s (at least from the latter’s perspective), leading to a joint publication in 1858 and making Wallace the (largely forgotten) codiscoverer of evolution by natural selection. In short, even before Darwin published Origin, “there was plenty of evolutionism around for those who had eyes to see it,” as Browne puts it.12