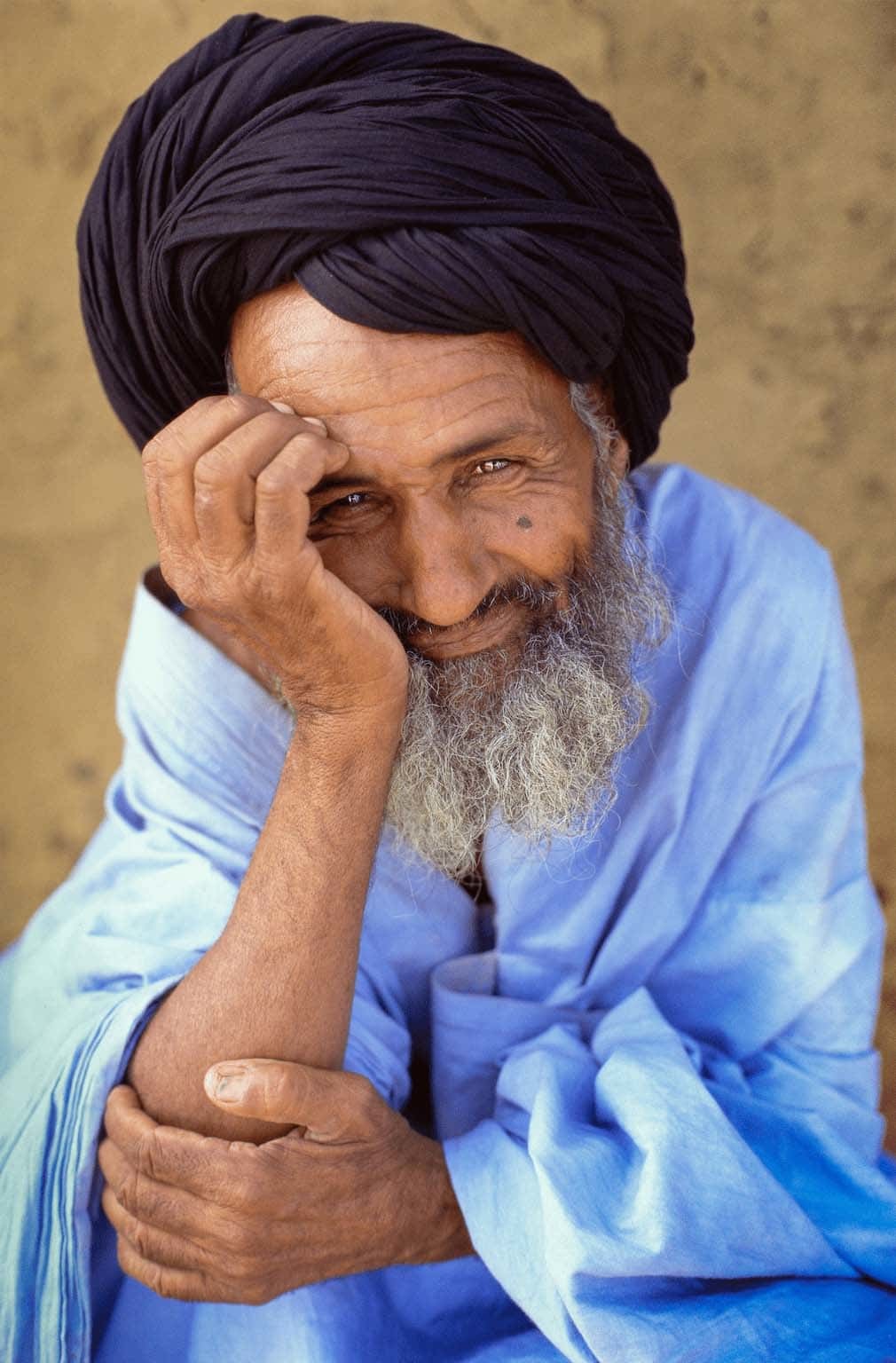

Master of the Times, Shaykh Muhammad Ali, Mauritania; photo: Peter Sanders

As a child growing up in England, photographer Peter Sanders, whose work portrays the humanity and rich tradition of Muslims around the world, learned through play what would become the foundational skills of his craft. Around the release of his newest book, Meetings with Mountains, he had a conversation for Renovatio with Youssef Ismail, a member of Zaytuna’s faculty and a well-regarded nature photographer himself. The book is a culmination of years of travel and encounters with men and women considered set apart in their relationship with God. Sanders and Ismail talk about creativity, training the eye to truly see, and the art of capturing light. Their conversation is edited for length and clarity.

Youssef Ismail: So, you’re a photographer. I lived off my photography for about four years until the economy decided I wasn’t supposed to be living off my photography anymore. It was an interesting ride. I want to start by asking, How did you end up on this path of photography?

Peter Sanders: As a child, I used my fingers to put a frame around things. It felt very natural for me. By closing in, I could exclude everything around the object or person that I did not want to see. My mother always had cameras, and I discovered later that my grandfather had been a professional photographer, with a studio in the King’s Road in Chelsea in London. He hadn’t been financially successful at it, and as I spent more time with him growing up, he had already left the profession. He died when I was sixteen. After he passed away my mother gave me some of his photographs, and they were really fascinating. He photographed some very interesting people like Pavlova, the Russian ballerina. When I was younger I used to sit with him, and he nurtured me with stories about travel and his love of images, and he transmitted something to me. We never got a chance to talk about his photography, but I think his artistry got passed down to me from his genes.

At some point, I got sixty pounds from a government tax rebate, so I bought a camera with two lenses from one of the big studios in London. One day I met my landlord on the train, and he said, “What are you doing with that camera?” I said, “I just started doing photography,” and he said, “That’s interesting. The guy that used to live in your flat did photography. He left some equipment. Maybe you can use it.” So, I inherited a whole set of darkroom equipment. I’m self-taught. I just fell into photography and started to take pictures of people, particularly in the music scene, and also created some album covers. During that time, I met someone who was the head of Buddha Records. He came to my house, and he had this big silver box, with Nikon and Canon bodies and various lenses, and he said, “What do you think about this?” I was like a kid in a sweetshop! He then said, “I don’t need it at the moment. You keep it. I’ll get it back later,” and he handed me the whole box. So, I started working with his equipment. I had a glass jar that I kept coins in, so whenever I had to go do a job, I’d take the coins for the bus fare. I worked like that for a year, and then money started coming in. I was able to buy my own cameras and give him back his cameras.

YI: Amazing. So, did you mostly focus on portraits of people that you were interested in photographing?

PS: Yes. It was mostly musicians and the whole ’60s scene. I cut my teeth in documenting all that was happening at that time. I worked largely in black and white. I didn’t feel I was very good at color at that point. My theory, for what it’s worth, is that there’s a certain stage when you see life in black and white, and then as you get older, you start to see there’s more to life than just black and white. There are subtle tones and colors—your whole approach changes. When I went to India, that’s when I really got into color.

YI: In graduate school I started looking for the crescent moon, and people didn’t believe I was seeing the crescent moon, so I decided I needed proof. I decided to try to photograph it, and that took me several months. I needed a better camera than the point-and-shoot that I had. I found a person on campus that was selling a Canon body with two lenses for fifty dollars. I bought it from him and fiddled with the knobs, trying to figure out what they do. Having an engineering mind, I worked it out. It took me a few months, but I finally managed to capture the moon on a piece of film. It was exhilarating. The process of waiting for the moon, watching how the light would change, how it interacted with the land, and how the land appeared to change just mesmerized me. Before I knew it, I was in the hills here in the Bay Area, running around photographing all the time. Most of my stipend went to film and developing, and I lived on peanut butter sandwiches to keep that going. The camera bug bit me, and I just kept going. I didn’t know what I was doing with all those photos; I just knew that something was calling me to do it.

PS: That’s what Ansel Adams says: “Sometimes I get to places just when God’s ready to have somebody click the shutter.”

YI: Right. Photography is a really good medium for teaching people how to see. When I used to run workshops, I would take people out, and they would come back unhappy with their photographs. I would ask them, “What were you trying to photograph? What did you see that made you want to take the photo?” And they would point out a very small section of the photo, “That’s what I wanted to photograph.” So I would say, “Why did you use the wide-angle lens? You’ve lost it in all the chatter that’s there.” It was interesting to see how people wanted to see things but didn’t know how to see them. Photography allows you to focus, especially when you put that camera up to your eye, and you have that frame, and it excludes everything else—you can concentrate on that small little portion that interests you and work on capturing it.

PS: The challenge for people, particularly nowadays, is that they’re not very present. Everybody is distracted, and capturing a photograph is a process. You need to calm yourself down, and once you do that, you start to see things. Otherwise, you’re just missing everything all the time. A lot of what we do with our students is just getting them to be calm and still, and then they can see things.

YI: And there’s so much imagery out there now.

PS: Yes, one source quotes that more than three billion images are uploaded on the internet every day.

YI: Last year, the estimate was that one trillion photographs were made in 2018. That’s a number you can’t even wrap your head around. It’s phenomenal.

PS: Imagery is a language that young people are using, but they need to know how to use it. We see an image in our mind first, and then the thoughts come after that; imagination is a process, a faculty that God has given us. We need to understand it because if you imagine things, if you really see them, it’s possible to make things happen, good or bad.

YI: When you see something, what attracts you to it? What’s the trigger?

PS: Life is the trigger, because when I first had a camera, I only took pictures when I was inspired and motivated. During the cultural revolution of the late 1960s I was witnessing and photographing “unique signs in a new age.” Then I spent the next fifty years searching and traveling around India, China, and the Muslim world, photographing everything I was interested in and felt I needed to document before it disappeared. Then the world shifted again for me. Photography moved from film to digital. I had to learn a whole lot of new editing skills to enable me to work with the new medium, but in the process I was able to create a unique archive of images that will form the basis for photographic, art, and educational projects that inspire me and, hopefully, others to think differently about the world we find ourselves in now. We need to change the narrative, and art for me is that conversation.

YI: I remember once I was in the Yosemite Valley, early in the morning. The sun had just crested the valley walls, and it was foggy and the light was streaming through these trees. I immediately knew exactly what shutter I would use, what aperture I would set up with, which lens I would use. Everything was already glued in. It just clocked right in. I jumped out, and within five seconds, I had the camera on the tripod and the shutter tripped. I could move on because I captured it exactly how I wanted. If a person doesn’t have that familiarity with the equipment, you’ll be fiddling and the light will vanish, because it’s so ephemeral.

PS: Photographers love to talk about equipment, but with this iPhone invention, it doesn’t really matter anymore. I guess it depends on what you’re going to use the end product for. If you’re proficient in using an iPhone, just use it. It’s not about equipment; it’s about the person and how they use it and for what purpose.

YI: When someone first gets into photography, they get very enamored of having the latest equipment and thinking that’s going to make a better photo.

PS: I saw this great ad that said, “Teach your children photography. They’ll never be able to afford drugs.”

YI: That’s hilarious. A few years ago, that solar eclipse passed over Redding, just north of here, for a few hours. It was an annular eclipse, so when the sun and moon were in conjunction, there would be a ring of light. I had photographed other types of eclipses, never thinking that I would capture a solar eclipse. But when I heard about this, I started preparing a year in advance, thinking about how I would do it, where I would go, where I would stand, what kind of composition I would do. That day, when the eclipse started, I don’t remember taking the two hundred photographs that I took in those two minutes, and yet I was watching it the whole time. It was because of familiarity with the equipment. You have to know what you’re doing.

PS: Exactly.

YI: When that eclipse happened, it was like looking into the eye of the Creator, because it was this hole in the sky, glowing, yet you could look right into it. My son and I looked at each other, and all we could say was, “Allahu Akbar,” God is great.

I needed eight exposures to capture the dynamic range from the brightest to the darkest moments, to get all the detail in the corona. But when I clicked that last button in Photoshop to pop everything in place, I almost fell out of my chair. I said, “That’s it. That’s exactly what I remember seeing.” I display it now in my shows, and people ask, “Did you take that? That’s exactly what I remember seeing.”

PS: I tend not to do nature photography, because I feel I’m not proficient enough in it. People like you spend a lot of time doing it, so I don’t need to. I need to work in the field that I know. But I admire it, because it takes a lot of time, a lot of waiting and a lot of patience.

YI: You’re known for the photographs of people you take on your travels. How is photographing as you travel different from studio photography?

PS: Studio work is my next challenge. I’ve traveled all over the world and now I want to get a small studio and just do portrait photography, one-to-one with people, because I’ve never done that before. It’s different because with travel photography you have the whole wide world as your backdrop, and the culture, and everything else. Doing a one-to-one with somebody and getting a great shot is difficult because most people feel uncomfortable. It’s intimate. You need to get past the discomfort that intimacy brings and get to who they are. There’s a successful British portrait photographer based in America whom I talk about in my workshops, called Platon, who says that what he does is only three percent photography, and the rest of it is psychology. To say something to someone, to break through to them in such a way that a real connection is made with them and captures the essence of them—that’s a real art, and it’s what I’m interested in now.

YI: When you photograph people on your travels, do you just take the photo, or do you need to get their permission ahead of time?

PS: I mostly always ask permission. A picture with permission is completely different from a picture that you steal. If that person gives you permission, they give you something. Particularly with the project Meetings with Mountains, I’m dealing with a whole group of people who have never or rarely been photographed before—I have to get their trust. And I’m not going to betray that trust. They are not coming with any masks on. They’re just real people. In one way, it’s quite challenging, and in another, it’s quite easy. Some of them are centurions; the eldest is 125. I don’t have a lot of time with them. They’re not going to sit for hours while I move them around.

I have this photo of a Shaykh from Libya who was in his eighties, which I took back in the day when film cameras were all mechanical and you viewed the meter through the lens. He was just sitting there and I was meeting him for the first time. I lifted my camera, and the meter needle was swinging from one side to the other, from too much light to not enough light. And he was waiting for me to take the picture. I was thinking, “What do I do?” And I just said quietly, In the name of God, and took the picture. Thank God, it came out.

YI: Did you have any idea why the meter was swinging so wildly?

PS: God knows best. Maybe to test me. In this particular zawiya the people recited the name of God continually out loud. It was a very powerful place. I had never been somewhere where people didn’t like to make small talk, but just walked around saying the name of God. I had just arrived from the UK, my luggage had not arrived, all I had was my cameras, and I went straight from the airport to this place and did the photos. That photo is in Meetings with Mountains.

YI: So, when you look at people, is there something that attracts you to want to photograph someone in particular?

PS: With that project, it wasn’t a who’s who of saints and sages. It was people that I had a connection with, and I wanted to show something of who they were. The challenge with photography is that there’s an outward form, and then there’s an inner form that is slightly hidden. So, it’s a matter of approaching them in a very real way and getting them to trust that you’re doing the best that you can. Many of them have never been photographed before. Not because they think photography is forbidden, but it’s from humility. They don’t have an ego, and they don’t want there to be anything that makes them appear as if they are somebody important, which is very different from the society we live in nowadays, where it’s all about “I, me, mine.” Also, they don’t fit the common idea of charismatic saints and miracle makers. These people are very real, and some of them are very poor. Some are even beggars, so the project didn’t fit the typical mold. In some ways, it was the opposite. But when you spend time with these people, and you get to know them, you realize they are extraordinary.

YI: You talk about this inner dimension that people have. Do you think that’s captured in the light that they emanate?

PS: I think so. When we launched the book in Bradford, one of our great scholars said something I never even thought about: and that was by looking at these people’s faces and reflecting on them, a narrative begins to take place between you and God.

YI: That’s power.

PS: It’s a very deep thing, because there is something in those faces. But you need to reflect on it a little bit.

YI: I’ve always pondered this idea, “What in the world is light?” It’s a very elusive medium. It has so many different facets, depending on how you approach it. Having a scientific background, I understand the physics behind light, but it’s still elusive. You can’t capture it. It just leaves an impression, and we can only try to capture that impression at that instant, before it’s not there anymore.

PS: And then there’s an inner light in people. It is kept hidden because if it was exposed, people would go crazy. It shines out whenever God wants it to show up for His purpose. It’s a different kind of light, like when people say the Ramadan moon is different from the others.

YI: Well, every moon has a different quality throughout the year. You see a Shaban moon, and you see the moons that bring you into Shaban. They have this festive quality about them. I wonder, Why is that one so different from the Ramadan moon, which usually comes in without any fanfare? There’s not a brilliant sky, nothing that’s glimmering; it’s just a very thin, little, humble sliver of light that appears in the sky, which is what Ramadan is designed, by its nature, to teach us: to become humble and not full of fanfare, because fasting is an internal practice.

PS: The ancients always looked at the skies.

Cradled; photo: Youssef Ismail

YI: It was the foundation of science: pondering how the sky moved, what those lights were, and why some of them moved in a peculiar way as opposed to others.

PS: When I met Muhammad Ali, the person I call the “Master of the Times” because he was the person in the Twemerit camp in Mauritania whose job it was to measure the prayer time using the movement of the shadow of a stick. He could even look at the sky and tell you what day of the year it was. That’s phenomenal if you have that skill. It was a beautiful meeting.

YI: That is my one regret about my visit to Mauritania: we went to visit him and he wasn’t home. I was lost looking at the skies there. At night, you can see your shadow from the starlight, that starshine. I never imagined being able to see my shadow from starlight. It’s absolutely amazing. But at the same time, with that much light in the sky, it’s overwhelming.

PS: I had a very interesting conversation with Dr. Abdullah Al Kadi while we were in the desert. We were discussing people’s shadows, and he referred to the Qur’anic ayat that talks about the shadows lengthening and shortening, and how the shadows prostrate. He explained that the shadow is an integral part of the human being, so it got me thinking that when I’m in a situation where the shadow is visible, I should try to keep the shadow in the picture if possible, and that was a shift in thinking for me.

Shaykh Hamza told me many years ago—I can’t quote exactly who it is from, but it’s somebody from the eleventh or twelfth century—“Whatever you do in life, whether you’re a doctor or a carpenter, or whatever your profession is, if you do it to the best of your ability, that will become a spiritual path for you, because you will learn everything you need to know about yourself.” I include photography in that because the nature of photography is to constantly reflect your condition back to you. It’s a blessing to be able to do these things and learn how to be creative. It is an art that you can apply to everything.

For nearly half a century, acclaimed British photographer Peter Sanders has traveled the earth to capture images of the saints of Islam. In the traditional world, these people of purity, knowledge, and illumination have been the role models, benchmarks, and exemplars of what it is to be human.