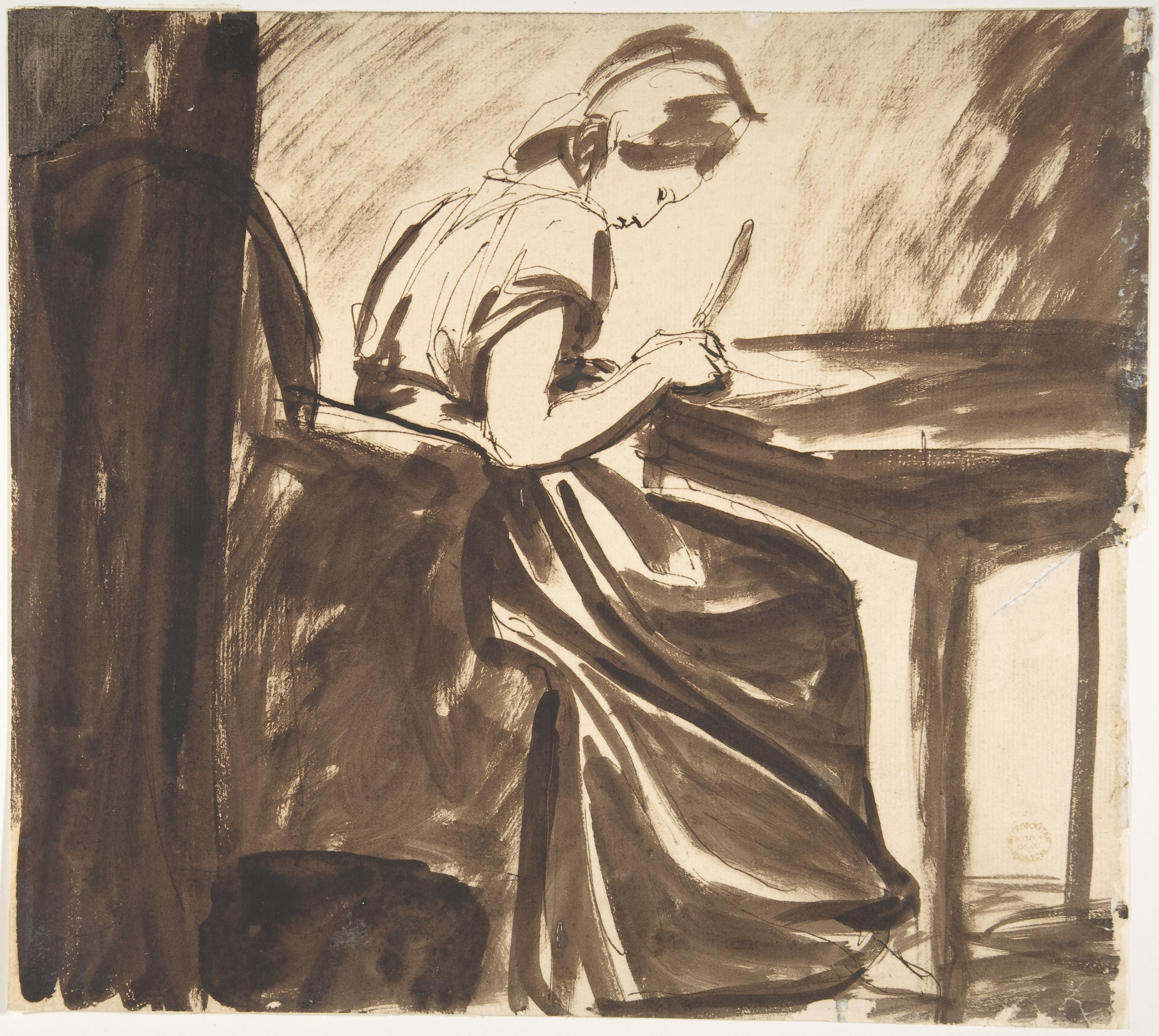

Lady Seated at a Table, George Romney, c. 1775

A woman named Harriet Verena Evans was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on April 28, 1782. She was forty-six years old when she began to keep a diary in 1827, following the sudden death of her seventeen-year-old son.1 Within it, we find a record of her spiritual reflections, including passages from scripture and religious poetry that she copied over a period of exactly seventeen years—from April 28, 1827, to April 28, 1844—as if in mimicry of her son’s lifespan. Her entries are not daily; rather, from the beginning, she establishes a pattern of dating that follows personally significant days in her calendar: the anniversary of the day before her son’s death (which is also her birthday), the anniversary of her son’s burial, Christmas Day, New Year’s Day, and her son’s birthday. The entire volume—running to some 240 pages—speaks through both its form and content not only to her grief and suffering but also to her faith. Turning her grief into a private confessional space on the page, Evans reflects on her eventual death and burial in the same sepulcher with her son and chronicles her prayers for family members as well as, in at least one instance, a vivid dream, brimming with religious imagery and the assured hope of salvation.

Overall, Evans’s diary is a concentrated, inward-looking account, impressing readers with interwoven themes of mourning and redemption. Very few current events are mentioned—for instance, an entry in July 1832 describes the arrival of cholera in Philadelphia. She makes no references to day-to-day tasks, outside of devotional practices. As a historical artifact, it primarily has resonance in the broader context of the Second Great Awakening, the Protestant religious revival that took place in the early nineteenth century in the United States, of which Evans appears to have been a part. Otherwise, in many ways, the bleak and unusual topography of the diary leaves today’s readers feeling rather like they have walked into a dark room and cannot find the light switch. Yet, as I read, I wondered what levels of catharsis Evans may have reached by keeping this diary, so marked by vigilance and her attentiveness to suffering as a gateway to better things: hope, constancy, self-awareness. What is achieved by keeping a record of one’s self, either as a diary, journal, or commonplace book? Could a regular habit of personal writing effectively address and either nullify or transmute suffering, even for those of us who might keep a diary or journal outside of an explicitly religious framework?

Diaries and journals are unique literary genres in that they are, by virtue of their personal nature, open-ended. They invite candor, creativity, and indeterminacy of form, making them particularly accessible. Anyone can keep a diary, in any pattern or for any length of time. Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) originated the essay genre with his Essais, which began as marginalia and notes from his reading, a written responsiveness akin to journaling that he viewed as healthy introspection. The British diplomat and Muslim scholar Gai Eaton (1921–2010) kept detailed records, which amounted to over eighteen million words, of his conversations and inner life for nearly eight decades, beginning at age eleven. The American poet and novelist May Sarton (1912–1995) published several of her stand-alone journals, which she kept at different points in life and which she used to wrestle with herself in old age and during illness. The European aesthetician and fiction writer Vernon Lee (1856–1935) jotted down notes about places she loved as part of her psychic healing after the First World War. Anne Frank (1929–1945) stylized her diary as a series of letters to her imaginary friend, Kitty, while she was in hiding, and it exists, remarkably, in two forms: one private and one expanded by Frank, with the idea of future readers in mind. Separated into twelve books and espousing his Stoic philosophy in both its form and content, the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius (121–180) was written as consolation only for himself.

Keeping a notebook prepares us for what may be coming, for what unresolved conflicts may be lurking and could materialize at any moment.

Forms of personal writing are useful in raising essential questions about ourselves: about our relationships with time; our access to cathartic release; our capacity for creativity; our interlacing of objectivity and subjectivity in our experience; and even our (implicit) interrogation of the limitations of personal writing to convey our real selves, which change and develop over time. Our twenty-year-old self is very different from our thirty-year-old self. In Arabic, the word for heart is qalb, meaning “to change” or “to turn.” The world around us moves at an alarming rate, and our hearts are obliged to apprehend the effects of changefulness both within and without. The writer Joan Didion (b. 1934) has likened her habit of keeping notebooks—about details in her day-to-day life, recipes she has tried, people she has met, scraps of conversations she has overheard—to the grander-scale task of remaining in touch with the emotional remnants that each of our past selves represents and passes forward. Keeping a notebook prepares us for what may be coming, for what unresolved conflicts may be lurking and could materialize at any moment. Far from rebuking the habit of keeping a (self-central) notebook as “self-centered,” Didion implies that it is a responsible act. It readies us for the unexpected return of past habits, vices, anxieties, or injuries. Our past selves, she explains, are like apparitions in the room with us, vying for our attention and suddenly making themselves felt. Better to know and understand them so that when they slip from the shadows into the light, we are ready.2

It is exactly that fine line between the self and the rest of the world that makes all forms of personal writing so morally contentious, particularly in times of suffering, when we are more likely to withdraw inward and concentrate attention on our own hurts and pangs. Gai Eaton, who compiled his autobiography in his eighties by using his diaries, found that certain pages revisited later in life, such as those concerned with obsessive and unrequited love, had something of the shuttered sickroom about them. Yet, from his experience, he concluded that focusing on one’s life via a diary is not without benefit. Eaton’s lifelong diary writing led him to the realization that nothing we experience in this world is trivial or commonplace and, by extension, that all human affairs have value. We are so constituted that self-reflection is capable of guiding our thoughts outward, inviting expansion. Even in moments when the rest of the world seems absorbed into our emotional landscape, newfound knowledge of the self percolates into our consciousness, and if the first opportunity is lost, our records remain for a future self to contemplate and see anew. In writing about our days, the things that drive us become more apparent. Themes emerge: evidence of continuity in the midst of change.

For Eaton, it was his obsession with the painful passage of time that both instigated his writing habit and became a recurrent subject. When his years at boarding school came to an end, for instance, he recorded his feelings of loss as they were tied to his sense of the unrelenting nature of time:

I’m too old to cry…. It’s after midnight and I’m cold and tired and sad, scribbling this by candlelight. What I feel is a very ordinary sense of grief, not worth describing, but it’s heavy. I’m not sad because it’s ended but because I shall change, forget, grow into another being out of sympathy with this “me.” I want to shout “Stop!”…. Listen to the wind in the trees, scattering the snow, and listen to the ticking of the clock. It seems to me that I have been granted an intimate glimpse of Time naked, something that it is not good for man to see. We must all hide the weak, timid creature that is in all of us, only allow it out by candlelight when the snow is falling.3

Later in life, Eaton identified this theme as a through line from his childhood to adulthood as well as a key motivating force behind his eventual conversion to Islam. Through an increasing self-awareness, he learned that his obsession with the passing of time was, at bottom, an obsession with discovering what did not succumb to time. In ways such as this, personal writing focuses our attention. It also, as Eaton describes, acts as “a safety valve” for the emotions that threaten reckless and selfish action, establishing instead a regular call to rumination.4 Eaton marveled, too, at its surprises. In the act of writing, he would often wonderingly put words to paper that startled him with their (self-)revelatory quality—so frequently a hidden, more real, consciousness and identity looked back at him from the page to uplift and refine.5

Podcast: Cultivating the Life Skill of Writing with Scott F. Crider and Sarah Barnette

Waterloo Bridge, Claude Monet, 1903

Eaton’s experience speaks to the idea that an improved quality of life emanates from personal writing. It clarifies our thinking and illuminates the reasons behind our opinions, while giving our hearts leave to unburden themselves. This was also the view of Michel de Montaigne. His basis for keeping a personal record was that the improved quality of conversation with the self leads to an improved quality of life overall. His choice of the word essai, which he coined from the French for “trial” or “attempt,” speaks to the truth of achieving a personal writing habit: it requires care and effort to strengthen, like exercising a muscle. The standard of our inner dialogue improves with time and application, and serves us well throughout life, particularly as a source of resilience in periods of suffering. Montaigne’s hardships—the sudden death of his closest friend, the death of his father, chronic illness—spurred him on to more and more “attempts” at self-examination, not fewer. Ultimately, he achieved a subtle interplay in his Essais between clear-eyed acknowledgment of his (subjective) limitations and an honest search for (objective) truth. Alongside Eaton’s account, Montaigne’s personal writings, today so prized, exemplify an inherent wisdom in keeping a consistent written record of the self, refuting the view that it necessitates selfishness or self-aggrandizement.

In the Meditations of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, we see a more idealized record of the self at work. Meditations is not a standard modern diary of individualized thoughts or enumerations of each day, yet it remains personal writing. In part, Meditations is an example of hypomnēmata, an ancient genre of “personal notes taken on a day-to-day basis” that aimed to gather and fix a person’s learning over the years in memory and action so that one’s moral ideals would be deeply embedded within oneself.6 It makes sense, then, that Marcus Aurelius wrote Meditations privately, for self-edification rather than publication. Acceptance, patience, fortitude, forbearance, serenity: these are the Stoic attributes Marcus Aurelius espouses throughout Meditations in order to keep them close to himself. The whole of Meditations can be construed as an exercise in personal transformation.

As emperor, Marcus Aurelius contended with floods, earthquakes, plague, rebellion, and multiple invasions along the empire’s borders that required lengthy military campaigns. He was chronically ill and frequently in pain. He suffered the loss of seven of his thirteen children in their childhood; the death of his wife, Faustina; and the death of his adoptive brother and joint emperor, Lucius Verus.7 Even in referring to his own approaching death, Marcus Aurelius keeps the Stoic approach to suffering before him—that is, that one should not compound suffering with undue anxiety or worry:

Do not draw inferences in excess of what first appearances report. Suppose it has been reported to you that a certain person speaks ill of you. This has been reported; but that you have been injured, that has not been reported. I see that my child is sick; that I see, but that he is in danger I do not see. Thus always abide by the first appearances and add nothing to them from within, and then you are unaffected. Or rather add this, the recognition that everything which happens is a part of the world order.8

Our task according to this call is to manage ourselves and our suffering in the present, rather than amplify it through regret for the past or apprehension for the future. If only one central doctrine of Meditations could be named, it would be that of recognizing the difference between what we can control and what we cannot. As a whole, Meditations is an extended effort on the part of a man well acquainted with suffering and the weight of responsibility for others to keep the Stoic model of an ideal man in constant view, and it speaks to the significant relationship between personal writing, memory, and morality.

Through examples and excerpts such as these, the diary and journal emerge again and again as instruments for self-knowledge and self-care. With these genres, we externalize what is within us and see our outpourings from a fresh perspective—like having a mirror to reflect the deeper, and so often today less accessible, places of our hearts and minds. Writing regularly arranges our thoughts, deposits us away from the clamor and the din when we can take it no more, and stirs our receptivity of more positive emotions—gratitude, love, happiness, hope, wonder—particularly in the midst of difficulties and suffering.

Much of our anxiety, fear, grief, and suffering originates in our hearts. Our hearts are malleable, in constant motion as they pump blood through our bodies; as a muscle they are also disciplined, their rhythm inspiring strength and consistency. Religious and spiritual traditions throughout history have emphasized the significance of our hearts and their interrelated physical and spiritual condition. Our hearts are the core of our ranging vascular system and are customarily viewed as the seat of our emotions and consciousness. The health of our hearts should then, likewise, be of central concern to us.9 The self-knowledge and resiliency that a personal writing habit affords us should not therefore be underrated.

Today, we are most likely to think about a self-care or purification process—either bodily or spiritually—in terms of “catharsis,” a word that implies transformation and a coming into light from darkness. Our positive and pragmatic understanding of catharsis largely stems from Aristotle. The word is only mentioned once in Aristotle’s Poetics, in reference to the effects of tragedy on its spectators as they move between feelings of pity and terror for the plight of the hero, but it has given rise to centuries-old debates on its meanings and uses. Early translators preferred to interpret it as “purgation”: that is, tragedy “purges” or expels the emotions. Its alternative meaning as “purification” has been favored from the seventeenth century onward, as emotions and affect became more valued: tragedy cleanses emotions rather than expunging them. A third gloss is of catharsis as clarification, which alludes to intellectual understanding, or the application of reason in the wake of extreme emotion.10 Narrowly defined, catharsis is tied to spectatorship and drama, but more broadly, it applies to the question of the value of art and literature: What effects do art and literature have upon spectators and readers? What effects upon writers?

Journaling itself has been used therapeutically since the 1960s, yet forms of personal writing go beyond the modern idea of therapy, which is the attempted remediation of a health problem.11 Part purification, part clarification, the catharsis that occurs through personal writing is a reconciliation between the self and the world: our emotions, imaginations, and experiences are synthesized with nature, society, and history. And we need this the most in times of uncertainty and suffering, because these are the periods in life when we are forced to concentrate on disruptions and disturbances. Suffering so directs our minds that it drives us to express, process, and distill our pain. Arguably, every spiritual tradition requires its votaries to practice concentration and seek a higher consciousness via prayer or learning or meditation. For modern Westerners, who may often lack an intimate connection to the specific religious framework of their forefathers, keeping a diary or journal is both a meditative and an intellectually stimulating means for catharsis and renewal. In this light, keeping a journal or diary is more than therapeutic: it reacquaints us with the interconnectedness of things, giving us access to a spiritual or sacred dimension of experience. Keeping a diary or journal can be likened to bringing the mythical into the everyday, leading us to find wonder in the mundane or to discover that a seemingly commonplace experience contains layers of meaning.

Regular writing rituals are about gifting time back to ourselves; they are about clearing a physical space on the page for the cleansing work of inward expansion to occur.

At times, personal writing is most useful because it reminds us that catharsis requires effort, space, and consistency. May Sarton regularly kept and published her journals, particularly later in life, as she came to grips with aging and illness. A well-known author, Sarton received many letters from readers over the years in which she noticed a thematic cry, not so much for space but for time in which to reflect and be still. Her journals seem like an offering to these readers. “Conflict becomes acute, whatever it may be about, when there is no margin left on any day in which to try at least to resolve it,” Sarton writes as she ponders this collective need in her Journal of a Solitude (1973), a journal she kept for one year while living alone in her rural New England home.12 The journal is replete with her attentiveness to nature and its cycles of life and death. The seasons, plants, cats, the passing of an elderly friend, the creaks and irregularities of the house—Sarton delves into them all. Even a temperamental raccoon and Sarton’s discovery of a dead mouse while cleaning a closet take on rejuvenating energy by the attention she affords them. She marvels at the new buds on trees, sunlight on a daffodil, the beauty of the nest made by the field mouse from pieces of wool and string. In her journal, readers are given the impression that it is the ritual of writing about experience that gives Sarton’s inner life shape and power. We commune with the world and with ourselves as we write, keeping our hearts soft and our minds flexible.

Sarton’s entries are animated throughout by her acute awareness that, without time set aside for solitude and reflection—through gardening, walks in nature, but most particularly through writing—one cannot process what happens in life, or intuit its deeper significance. Sarton seems to be speaking to each of us when she writes about journaling as a mode of analyzing experience, a way forward out of cluttered days and cluttered feelings, what she calls our “thickets of undigested experience.” 13 She teaches by example that regular writing rituals are about gifting time back to ourselves; they are about clearing a physical space on the page for the cleansing work of inward expansion to occur. Sarton is not at all flippant about journaling. On the contrary, the language she uses to describe her Journal of a Solitude demonstrates her recognition of its deeply purifying and clarifying capabilities: “Now [with this journal] I hope to break through into the rough rocky depths, to the matrix itself. There is violence there and anger never resolved.” 14

During and following the First World War, the writer and historian Vernon Lee grappled with violence and loss as she maintained a collection of entries under the heading “Genius Loci,” or Spirit of Place.15 In them, she welcomes the interplay between history, mystery, and memory in an attempt to come to terms with the ill effects of the war. In the summer of 1917, while in exile in England and unable to return to her home in Italy, Lee wrote bleakly about mainland Europe:

I find myself staring idiotically at the photographs of devastated Reims, much as I stared incredulously, when a child, at the illustrated papers showing the Tuileries and the Hotel de Ville, which the Parisian Insurgents had just burned down. I do not really believe in that Reims lying in ruins; the Reims in my mind is too familiar and credible:.... But it is there no longer. And some day I shall recognize that, and disbelieve in all except its ruins. 16

Even when she returned to Europe and found altered hillsides; destroyed buildings; and later, war promenades and memorials in every village and town, she used her writing to identify meaningful symbols among the everyday things with which she came into contact. Personal writing became a crucial part of her process of psychic healing. As such, many of Lee’s entries are evocative, distinctive descriptions of places and objects across Britain and Europe: a little bit of worn glass found in Italian soil, prayers on pieces of paper in a German church, a row of horse chestnut trees beside an English coastal house. An aesthete and historian, Lee was alert to the layers of history in each place she visited, and her writing reflects her long-standing interests in nature, art, and culture. She renders her outpourings in a creative connection with the genius loci, historically a Roman deity. The term also refers, in a modern sense, to the ambiance of a small locality. Lee defines her understanding of the genius loci obliquely, sometimes naming it a deity but overall implying that it consists of the “delicate virtues” that spring from our attentiveness to places and objects: gratitude, hope, humility, peace, love, and goodwill among them. She finds it one autumn after the war in Ravenna, Italy:

Underneath the Lion of St Mark, while looking up at that rather lovely Tuscan Madonna and child and broken Putti [cherubs] and garlands on high, my eye fell on the freshly worked garden soil. And in it was caught by a tiny metallic sparkle, a little bit of iridescent pattina’d glass. I took it away. For, just because it may be either a bit of last year’s broken flask, or a fragment come down from antique days but equally made exquisite by earthly opalescences, it is, I think, an emblem of just such impressions as this market garden in the Ravenna castle, and all similar places, have given, and will always give, my grateful heart.17

Lee’s genius loci notebooks exemplify ways in which personal writing focuses, channels, and transforms our emotions, magnifying our reasons for positive feelings, such as gratitude. In a period marked by exile, lost friendships, nostalgia, and grief, Lee manages to metamorphose her painful emotions into a more expansive and hopeful outlook.

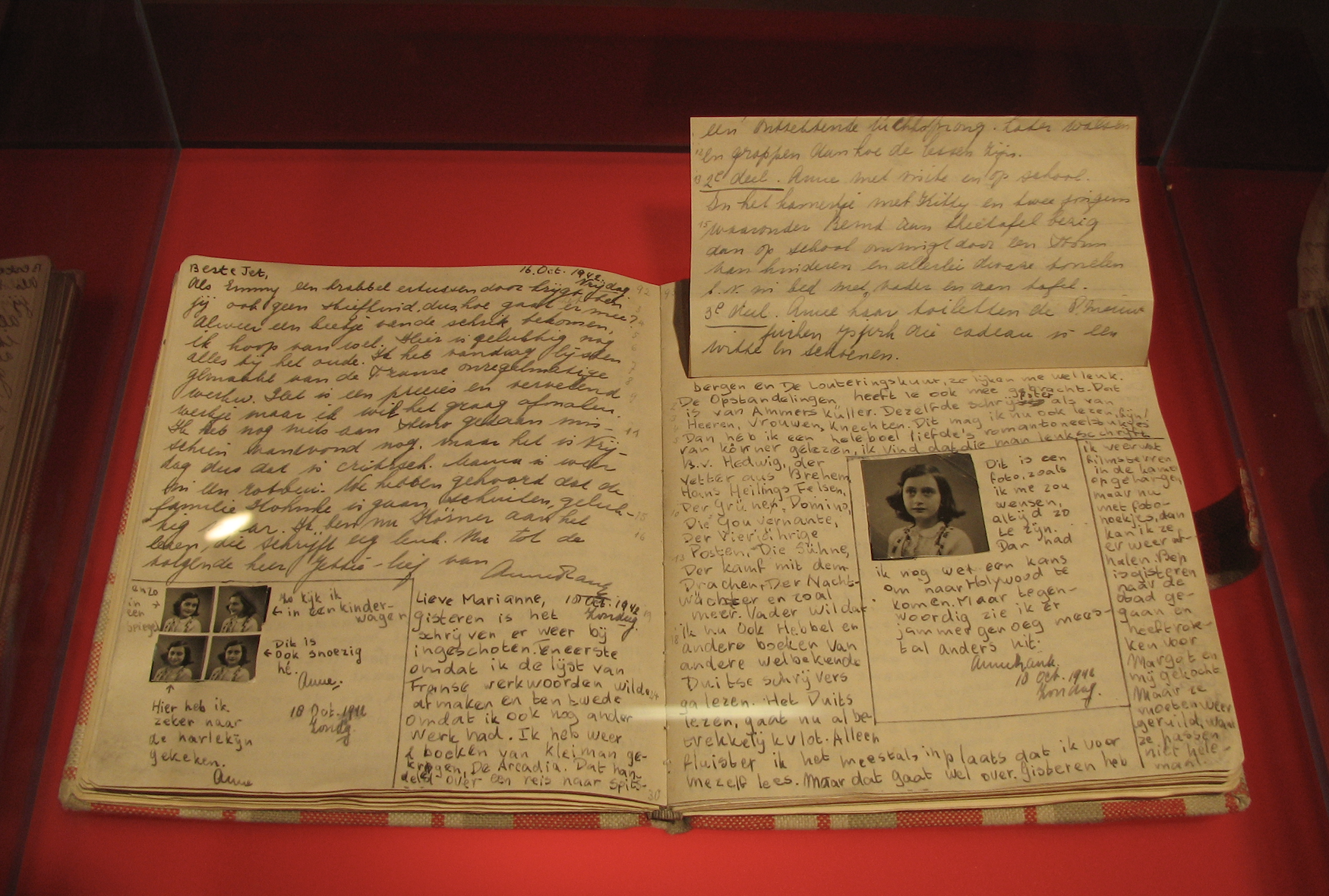

Pages from Anne Frank’s diary at the Anne Frank Museum in Berlin; photo: Heather Cowper

Yet perhaps in no journal is wartime suffering more emblematic than in the written record of Anne Frank. Frank’s diary was a gift for her thirteenth birthday on June 12, 1942. She began to write in it immediately and brought it with her when she and her family went into hiding from the Nazis on July 6, 1942. She wrote in it consistently until their discovery and arrest on August 4, 1944. Her last entry was August 1, 1944. Aspiring to become a journalist, in March 1944, Frank had begun to further edit and revise her diary for future publication. The result is a double record of Frank’s evolving inner life, her skills of observation, and her aptitude for storytelling—all presented through her conversations, dreams, prayers, reading, and comments on the conditions of her family’s life in hiding. Frank, together with her mother, father, sister, and four other individuals, lived in very close quarters. They experienced personal tensions; a near-constant fear of discovery; and limited access to food and nutrition, due to rationing. Throughout it all, Frank was still an adolescent girl with hopes, ideals, and yearnings, trying to come to terms with who she was and who she wanted to be.

She is explicit about why she began to keep a diary: she wanted a friend and stated, “To enhance the image of this long-awaited friend in my imagination, I don’t want to jot down the facts in this diary the way most people would do, but I want the diary to be my friend, and I’m going to call this friend Kitty.”18 About three months into their time in hiding, Frank added at the front page, “So far you truly have been a great source of comfort to me, and so has Kitty, whom I now write to regularly. This way of keeping a diary is much nicer, and now I can hardly wait for those moments when I’m able to write in you. Oh, I’m so glad I brought you along!”19 Frank’s diary reveals her methods for mitigating hardship and suffering through a combination of prayerful entries, self-questioning and self-analysis, efforts to empathize with others, and expressions of gratitude. At times, she writes in the second person directly to people she knows or has known, such as her friend Hanneli, whom Frank feared had already died. She also writes directly to God.

In one passage worth reading in full, Anne exhibits a heightened level of self- and other-awareness regarding her past actions. In dialogue with herself and Kitty, she examines her conduct toward her mother during the first year and a half of living in the annex and performs a stunningly wide range of empathetic imaginings:

Dear Kitty!

This morning, when I had nothing to do, I leafed through the pages of my diary and came across so many letters dealing with the subject of “Mother” in such strong terms that I was shocked. I said to myself, “Anne, is that really you talking about hate? Oh, Anne, how could you?”

I continued to sit with the open book in my hand and wonder why I was filled with so much anger and hate that I had to confide it all to you. I tried to understand the Anne of last year and make apologies for her, because as long as I leave you with these accusations and don’t attempt to explain what prompted them, my conscience won’t be clear. I was suffering then (and still do) from moods that kept my head under water (figuratively speaking) and allowed me to see things only from my own perspective, without calmly considering what the others—those whom I, with my mercurial temperament, had hurt or offended—had said, and then behaving as they would have done.

I hid inside myself, thought of no one but myself, and calmly wrote down all my joy, sarcasm and sorrow in my diary. Because this diary has become a kind of scrapbook, it means a great deal to me, but I could easily write “over and done with” on many of its pages. I was furious at Mother (and still am a lot of the time). It’s true, she didn’t understand me, but I didn’t understand her either. Because she loved me, she was tender and affectionate, but because of the difficult situations I put her in, and the sad circumstances in which she found herself, she was nervous and irritable, so I can understand why she was often short with me.

I was offended, took it far too much to heart and was insolent and beastly to her, which, in turn, made her unhappy. We were caught in a vicious circle of unpleasantness and sorrow. Not a very happy period for either of us, but at least it’s coming to an end. I didn’t want to see what was going on, and I felt very sorry for myself, but that’s understandable too.

Those violent outbursts on paper are simply expressions of anger that, in normal life, I could have worked off by locking myself in my room and stamping my foot a few times or calling Mother names behind her back.

The period of tearfully passing judgement on Mother is over. I’ve grown wiser and Mother’s nerves are a bit steadier. Most of the time I manage to hold my tongue when I’m annoyed, and she does too. 20

Frank holds herself to account. She not only considers the feelings of her imaginary friend, Kitty (as the recipient of so much “hate”), but also thinks vividly about the effects of her actions on her mother. She acknowledges the role of their difficult circumstances, even expressing sympathy for her past self. In this instance, Frank’s diary writing brings her starkly up against her failings toward others and facilitates a burst of self-awareness.

Throughout Frank’s diary, we see clearly that challenges and suffering go hand in hand with maturation and growth, with an increased aptitude for self-analysis and improved other-awareness. As her awareness of the suffering around her increased, so too did her cultivation of an inner, contemplative self:

It’s utterly impossible for me to build my life on a foundation of chaos, suffering and death. I see the world being slowly transformed into a wilderness, I hear the approaching thunder that, one day, will destroy us too, I feel the suffering of millions. And yet, when I look up at the sky, I somehow feel that everything will change for the better, that this cruelty too will end, that peace and tranquility will return once more. In the meantime, I must hold on to my ideals. Perhaps the day will come when I’ll be able to realize them! 21

Frank’s diary writing keeps her perceptive, hopeful, and alive to her needs, desires, questions, limitations, and faults in the midst of impossible pressures. Writing regularly became an unburdening process for her and a chance to self-expand for the benefit of herself and others. “I want to be useful or bring enjoyment to all people, even those I’ve never met. I want to go on living even after my death! And that’s why I’m so grateful to God for having given me this gift, which I can use to develop myself and to express all that’s inside me! When I write I can shake off all my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived!”22

I would argue that without a personal writing habit, the space and time that should be dedicated to the work of inward contemplation and self-reflection is rarely set aside or comes only in infrequent and harried bursts. And yet the inward and the outward are so closely knitted that to ignore one is to walk blindly through the other.

More than one diarist has conceptualized writing in a journal or diary as recourse to a ritual, meditative space. Thinking along these lines can direct us to a more literal space of meditation: the meditation labyrinth. Walking a meditation labyrinth is an ancient practice for contemplation and prayer, one that merges outward movement with inward stillness. It brings us back to the conception of the heart (qalb) as something that turns and changes. The soft, guided turns in a meditation labyrinth are sweet to hearts and minds engaged in inward attentiveness. It is perhaps, then, relevant to note that the Latin word for heart, cor, connotes centeredness and stability. Both the Arabic and Latin meanings are present in the design of a meditation labyrinth as a series of curved pathways woven around a central point. To my mind, and with the examples in this essay in view, personal writing constitutes a similar synchronous infolding stillness and unfurling movement. To return to Harriet Verena Evans, her diary is so structured that it speaks to a cathartic movement across the recurring theme of her son’s death. From this, she ultimately drew forth a message of mercy and also, I imagine, found a measure of repose:

Our dust shortly shall be blended together; and who can tell but that this providence might chiefly be intended as a warning blow to me, that these concluding days of my life might be more regular, more spiritual, and more useful than the former? – O may I be deeply humbled before my God, with a sense of my past sins and neglegencies [sic]! 23

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy