Tradition as a Human Affair

The Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre asserts that a tradition—true to its Latin etymology (traditum, meaning “what is handed down”)—is inherited by new “bearers” with each successive generation. Those who live in the present participate in a tradition as much as those imagined to embody the past. It is not, however, only a matter of receiving tradition. Each bearer of tradition plays a role in discerning and perpetuating it. Tradition survives only as much as its human recipients desire to carry it forward. Change inevitably accompanies tradition’s path forward. For modern thinkers about tradition, human agency is inevitably at work in the formation, adaptation, and perpetuation of a tradition.

This is, for example, the underlying principle of Talal Asad’s notion of “discursive tradition,” arguably one of today’s most influential anthropological theories of tradition. Asad’s explanation is worth quoting at length:

A tradition consists essentially of discourses that seek to instruct practitioners regarding the correct form and purpose of a given practice that, precisely because it is established, has a history. These discourses relate conceptually to a past (when the practice was instituted, and from which the knowledge of its point and proper performance has been transmitted) and a future (how the point of that practice can be best secured in the short or long term, or why it should be modified or abandoned), through a present (how it is linked to other practices, institutions, and social conditions)… it will be the practitioners’ conceptions of what is apt performance, and of how the past is related to present practices, that will be crucial for tradition, not the apparent repetition of an old form.4

Asad’s definition of tradition shifts the starting point for tradition away from ideas and onto practice—from orthodoxy to apt performance. Orthodoxy, of course, still matters, but it is not understood as a fixed or abiding “body of opinion.” Rather, Asad argues, orthodoxy is as “a relationship of power,” specifically “[w]herever Muslims have the power to regulate, uphold, require, or adjust correct practices, and to condemn, exclude, undermine, or replace incorrect ones.”5 Traditions are the means through which orthodoxy is developed in that they entail a constant process of negotiation, reasoning, and resistance. To borrow Ebrahim Moosa’s language, tradition “prefigures orthodoxy.”6

From the perspective of theology, these theories of tradition share a common limitation. Each casts tradition fundamentally as a human affair. But anthropology tells only part of the story. Theology, of course, is concerned with humanity, but that concern always relates to God. In fact, theology is more properly described as a discipline concerned with talking about God (theos + -logos “an account of God”), or rather with God. Whatever understanding of tradition is adopted by theology, it must account for both God and man to maintain any lasting coherence.7

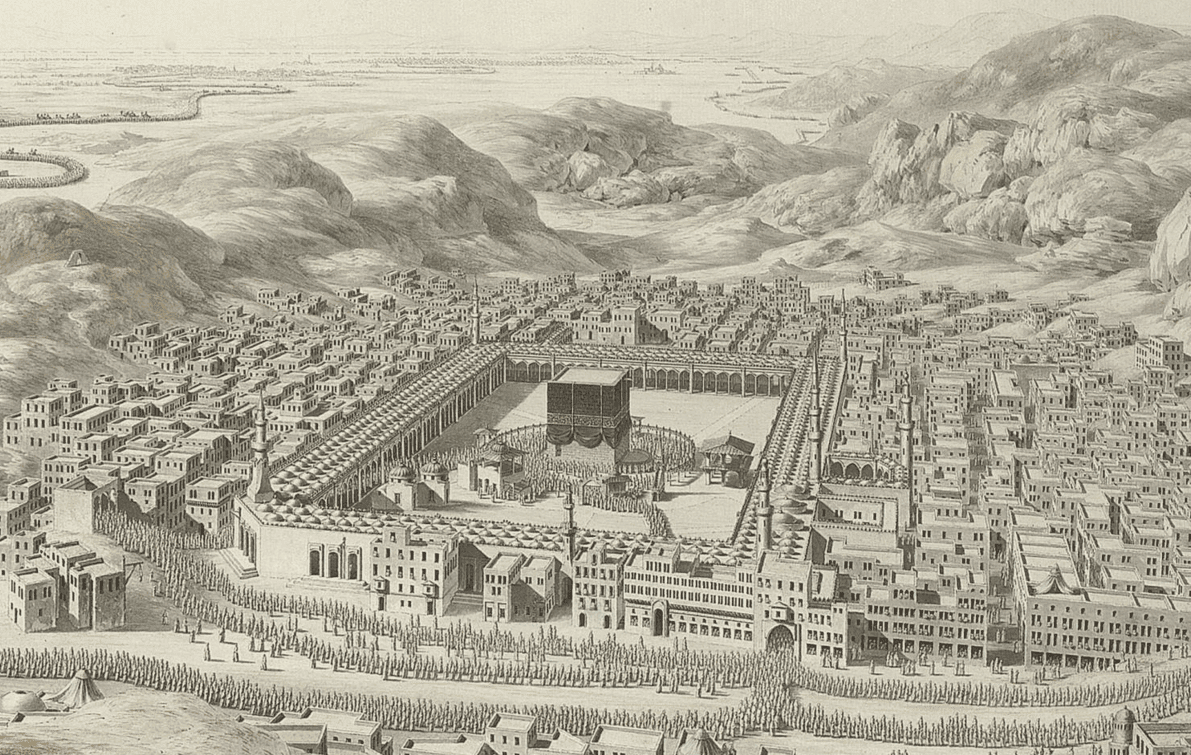

One way to do this is to understand tradition as a story, through what scholars call a narrative theology of tradition. For Muslims, the life of the Kaaba, the sacred structure that lies at the heart of the city of Mecca and to which Muslim prayer and pilgrimage is oriented, offers a faith-oriented reading of Islamic history that also sheds light on important elements of tradition.8

Reimagining Tradition

Both the Kaaba and tradition issue from a sacred source. Just as the Kaaba is indebted to the divine decree for its establishment, tradition likewise owes its genesis to God. Tradition would not exist were it not for God sending down revelation. In this way, tradition claims a sustaining heavenly connection. The Kaaba, in addition, plays a central role in God’s working within the world. It is where God has foreordained events of immense significance. To the Kaaba God has sent a procession of His prophets, and to it still God calls the attention of the faithful. The Kaaba has figured into many of the stories we’ve received about God’s prophets and messengers, from Adam to Abraham and Ishmael to the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ. It remains a testament and sign of God’s presence in the world as history continues to unfold according to His decree. The Kaaba pervades the consciousness of every believer because it is the ritual axis around which both prayer and pilgrimage revolve. In a resounding moment of divine intervention, God reveals to the nascent Muslim community that the sacred sanctuary is in fact the new qiblah, the direction to which prayer should rightly be oriented. “We have seen you turning your face to heaven, so We shall turn you to a direction of prayer that will please you. Turn your face in the direction of the sacred place of prostration” (Qur’an 2:144). From the moment of this revelation until the end of time, the Kaaba becomes the direction for all Muslim prayers. God returns the ritual attention of believers upon His house, making its place in Islam central. Is not tradition, the Islamic tradition, the same? Is its sacred source not also God? And is its role not central to life in this world and the attainment of a goodly hereafter?

Pressing further back into the past, the Kaaba’s beginnings lie in illo tempore, in a time before time. As related copiously in Qur’anic commentaries, historical chronicles, and tales of the prophets, Adam and Eve reunite in the valley of Mecca after descending from Eden.9 Here, God commands Adam to honor the first sanctuary, the first iteration of the sacred house, as a site of remembrance and worship of God. Through Adam’s labor the valley of Mecca is made into “an earthly substitute for the garden of Eden.”10 The Kaaba and the holy sites associated with reflect the celestial realm, a now lost paradisiacal domain, while simultaneously existing as an accessible, physical reality in this world. The perpetual orientation of the faithful to the Kaaba in this life is merely an echo of their orientation to God in the realms of the hereafter. At one and the same time the sacred house is a place of both heaven and earth. Here is Islam’s axis mundi, the spiritual center around which the world is arrayed.11 Tradition, in like fashion, exerts a centripetal force upon believers as they abide in this passing world. It is an axis that orients and directs the faithful towards God.

Yet as much as the Kaaba is the house of God, revelation also describes it as a house of human making: “And when Abraham and Ishmael raised up the foundations of the house” (2:127), the Qur’an reminds. Anchored on the earth, the house of God is a thing of history subject to the attention and neglect of its human custodians. Though rebuilt by Abraham and Ishmael, its stones are still subject to the vicissitudes of time. Each generation must tend to the Kaaba lest it fall into ruin or disrepair. Likewise, the life of tradition depends upon the work of successive generations, each laboring to protect and shepherd it through the ravages of history.

The fortitude of the Kaaba’s custodians ebbs and flows over time. As centuries passed, those who clung to Abraham’s legacy and honored the Kaaba’s original purpose gradually found themselves driven to the periphery. Polytheism displaced monotheism until the Kaaba became a sanctum for idols. Those who cleaved still to the worship of the one God, the few ĥunafā', retreated to the vicinity’s surrounding mountains, the margins of Mecca itself. The Kaaba may abide, but its purpose does not. Only five years before the first Qur’anic revelation descended upon the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ, we arrive at the pinnacle of negligence. The house of God had faded to a mere shadow of what it had once been. Early Muslim chronicles record that the Kaaba stood as nothing more than a square of loose stones rising to just above a man’s height, plundered and left roofless by preceding generations.12 Only at this abysmal low did the tribe of Quraysh resolve to remake it.

The uncertain periods between prophetic messages testify to how readily humans can stray and forget, even when living in the presence of God’s house, as the Arabs did. Consider the dereliction of the Kaaba from the time of Adam to the time of Abraham and then from the time of Ishmael to the time of Muĥammad. In this way also, tradition resonates with the story of God’s sacred house. Is not tradition likewise a trust passed down by our successive generations to be preserved and protected? But has not this trust been neglected at times by those who are supposedly its guardians? Are we not also struggling to maintain the integrity of the tradition as we understand it?

Nor does the saga of the Kaaba conclude with the end of prophecy. The history that stretches from the Prophet Muĥammad’s passing to today chronicles numerous accounts of how humans and natural events have harmed the Kaaba. As in times past, the state of the Kaaba rises and falls with the human condition.

Half a century after the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ, the early Muslim community found itself divided by seemingly unceasing civil war. The Umayyads besieged Mecca and its recently restored sanctuary when ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Zubayr (d. 73/692), a companion of the Prophet ﷺ born in the early years of Muĥammad’s time in Medina, decried the legitimacy of the Umayyad Caliph Yazīd b. Muʿāwiyah (r. 60—4/680—3). When forces loyal to the Umayyads marched against Ibn al-Zubayr, he took up arms and resisted, while fortifying himself in Mecca. It was under Ibn al-Zubayr’s banner that the Kaaba suffered its first real wound in the post-prophetic era. The chronicles report, “They [the supporters of Ibn al-Zubayr] were causing fires to be lit around the Kaʿbah. There was a spark which the wind blew; it set fire to the veil of the Kaʿbah and burned the wood of the Sacred House on Saturday, 3 Rabīʿ al-Awwal” in the year 64/683.13 One witness attested:

I came to Mecca with my mother on the day the Kaʿbah was burned. The fire had reached it, and I saw that it was without its silk veil. I saw that the Yemenī corner of the Kaʿbah was black and had been cracked in three places. I asked, “What has happened to the Kaʿbah?” They pointed to one of Ibn al-Zubayr’s followers and said, “It has been burned because of this man. He put a firebrand on the tip of his spear; the wind made it fly off. It struck the veils of the Kaʿbah between the Yemenī corner and the Black Stone.”14

The house of God, although proclaimed by revelation to be a sanctuary for humankind, was made by men into the opposite. War fires and arms filled the Kaaba’s vicinity, and the followers of Ibn al-Zubayr lapsed in their watchfulness and set God’s house aflame. In the wake of the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ, his divided community allowed the sacred house to smolder and burn.

Nonetheless, the Kaaba was restored, but the restoration was short-lived. Less than a decade later, ʿAbd al-Mālik, the fifth Umayyad Caliph (r. 65—86/685—705), sent al-Ḥajjāj b. Yūsuf (d. 95/714) to end Ibn al-Zubayr’s resistance in Mecca. Tensions escalated again, and blood was shed on the plains of ʿArafa, the supposed place of Adam and Eve’s earthly reunion and the site from which the Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ delivered his final sermon and received the last revelation: “Today I have perfected your religion (dīn) for you, completed My blessing upon you, and chosen as your religion Islam” (Qur’an 5:3). For six months and seventeen nights, al-Ḥajjāj besieged the city of the house of God; engines made by men hurled stones at the sacred mosque and its quarters, bombarding and shaking the walls of the Kaaba. One witness attested:

I saw the trebuchet (manjanīq) with which [stones] were being hurled. The sky was thundering and lightning, and the sound of the thunder and lightning rose above that of the stones, so that it masked it. The Syrians considered this ominous and withheld their hands. But al-Ḥajjāj… picked up the trebuchet stone and loaded it. “Shoot,” he said; and he himself shot with them.15

Here is a testament to human hubris—to transgress rather than uphold what is proclaimed sacrosanct by God. How often has the tradition also been subject to similar hubris? As for the Kaaba, battered as it was, its fallen and cracked stones would eventually be set aright.

This legacy of human devastation and ruination of the Kaaba continues. In the early 4th/10th century the zealous Qarmaṭīs of al-Baĥrayn brought trauma to Mecca once more. Under the leadership of Abū Ṭāhir al-Jannābī (d. 332/943-4), the Qarmaṭīs assaulted and captured cities throughout Iraq. Before long their sights turned to the holy city of Mecca, and on their push southward, they attacked caravans and pilgrims along the way. They arrived at the city on the 7th of Dhū al-Ḥijjah, 317, one day before the Ḥajj pilgrimage was set to commence. The days that followed were filled with violence. For eight days, the Qarmaṭīs of Abū Ṭāhir plundered the city and massacred pilgrims. The blood of the pious soaked the ground of the ĥaram. In a final imperious act of defiance, the Qarmaṭīs tore the Black Stone from the Kaaba and carried it away.16 They carried away the stone sent down by God, the same blessed stone carried and cared for by prophets. What seemed inviolable was violated. But in 339/951, after twenty-two years of captivity, the Black Stone was returned, and the house of God was restored.

Even in recent times, the Kaaba weathered the storm of human history. On November 20, 1979, Juhaymān al-ʿUtaybī and his fervent followers captured the sanctuary of the Kaaba, taking thousands of the pious hostage.17 As in times past, only force and violence could repel the war and bloodshed that had entered the holy sanctuary. But even this trauma, still in living memory, was not beyond reversal. Repeatedly through the ages, and in accordance with the will of God, we find the community of the faithful toiling to restore and preserve the Kaaba after human actions harm it.

We should imagine the Kaaba and tradition as cut from the same cloth. God establishes and watches over both, but their temporal lives yield to the volatility of human care and neglect. Through them, we find a connection with divinity. And while they are human constructs, both exist as referents to God. How precarious does their existence seem when entrusted to human stewardship, yet how vital they are for sustaining prayers and faith, and how constant they have been as the community of faith struggles through the world!