A second factor relates to the loss of power by Muslims over their own territories, via invasion, collaboration, and colonialism. This is less about power as purely political and more about how the loss of political power weakens ideational power and the independence of religious academic institutions, further reducing the lack of mastery over the Islamic tradition. Noting quite how power is relevant here is direly important to distinguish because it is clear that the postcolonial era has been at least as damaging to these knowledge-producing institutions as was the colonial era. In this period, muftis arose without the same depth of knowledge in uśūl al-fiqh their predecessors had; theologians emerged without the same awareness of the breadth of ¢ilm al-kalām those who came before them had. A mastery of nonreligious knowledge, such as the natural sciences, became even rarer, though it continued nevertheless.

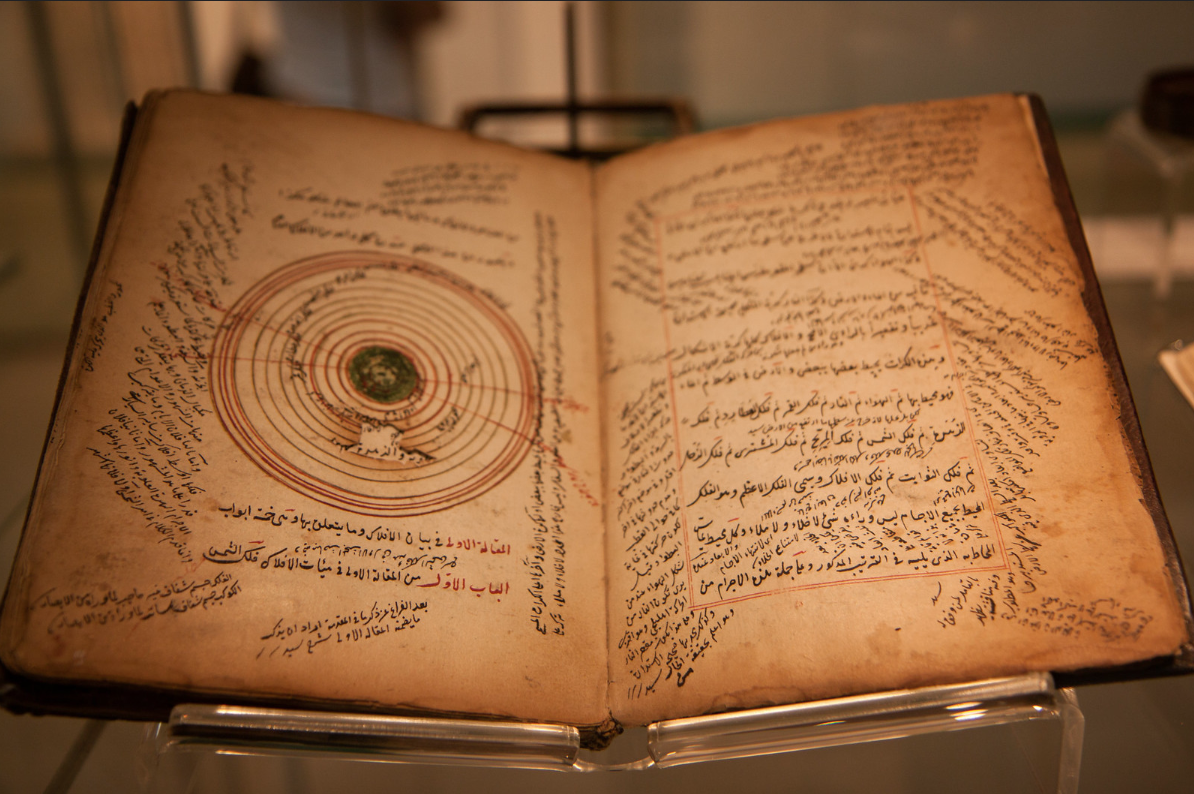

It has been reported that the qualifications for imam of the Grand Mosque of Istanbul in the sixteenth century included, among others, mastery of Arabic, Latin, Turkish, and Persian; familiarity with the Bible and the Torah; and competency in mathematics and physics. There may be some exaggeration here; even so, the level of wide-ranging knowledge expected of such a religious figure is staggering, especially compared with what is expected of holders of such posts throughout the Muslim world today.

A third and final factor relates to ideational challenges within Muslim communities. The rise of purist Salafism (derived from interpretations of Muĥammad b. ¢Abd al-Wahhāb’s legacy) presented a significant confrontation to mainstream Sunnism, much of which it described as shirk or bid¢ah. Later, modernist Salafism (beginning with Muĥammad ¢Abduh, and continuing through Rashīd Riđā and his intellectual progenies) gave rise to different reformist political movements. The ideational trend behind those movements was, indeed, deeply modernistic and sought to redesign existing Muslim institutions of learning, thereby affecting the Muslim religious establishment. The Muslim religious establishment was often resistant to this trend, seeing it as diverting from normative Sunnism in different ways.

Each of these phenomena—the quickening of change, the colonial-postcolonial enterprises, and the internal ideational agitations—would be enough individually to severely disrupt the development of the religious establishment and the continued advancement of the tradition. But coming together as they did, they became a significant obstacle to the traditional structures with respect to preparing and producing scholars capable of bringing the proper weight of the tradition to bear on contemporary issues. Instead, more often than we would wish, beleaguered Muslim scholars understand their tradition as they would a typewriter, when today’s challenges require it be understood as a supercomputer. There remain some who can do the latter, but, indeed, they are rare.

Historical Muslim Engagement with Change

Some scholars, such as Imam Ĥārith al-Muĥāsibī1 and Imam Abū Ĥāmid al-Ghazālī, have recognized the integral tools within the Islamic tradition to respond to change. We might term their recognition the Muĥāsibian, or Ghazālian, impulse. We saw this impulse in theology and its related philosophical sciences within the Islamic canon (¢ilm al-kalām and falsafah). When it came to issues surrounding the sacred law (sharī¢ah), we saw the same impulse: past jurists developed a deeply sophisticated legal heritage and set of methodologies for responding to changing circumstances. We know of figures such as al-Ghazālī and al-Muĥāsibī precisely because they were trailblazers. Indeed, such figures often had rather harsh words for many in the scholarly communities of their times. They often directed their criticisms at what they perceived as weaknesses in responding to change, although they held other critiques as well.

We might note how al-Ghazālī engaged with Avicennian-Aristotelian science and compare his engagement to contemporary Muslim responses to Darwinian theories of creation. Al-Ghazālī predicted humiliating consequences for the entire community if unprepared religious scholars attempted to refute theologically suspect aspects of science, writing, “The harm inflicted on religion by those who defend it improperly is greater than the harm caused by those who attack it properly.”2 In his view, a scientist would only mock half-baked responses by a theologian; at the very minimum, then, he expected the religious critic to painstakingly separate objective science and empirical fact from subjective results and interpretative inferences. Al-Ghazālī demonstrated such a model of critique by carefully analyzing and categorizing each premise of Avicennian-Aristotelian science.3

Importantly, scholars such as al-Ghazālī recognized their own limitations, a characteristic common in the past but less common today.4 For example, whereas most premodern experts in law were unwilling to judge when a legal issue overlapped with scientific principles (in recognition of their own area of expertise and their lack of training in other disciplines), some present-day scholars, such as experts in the field of prophetic traditions, the muĥaddithīn, feel empowered to go beyond their field of expertise, without having the requisite training or perspective in other fields.

A case in point from our legal history is the great al-Nawawī (d. 676/1277), who deferred the question of defining the physical extent of the local sighting zone of the new crescent to astronomers. He plainly acknowledged that astronomy was not one of his areas of expertise and deferred (i.e., made taqlīd) on this particular argument to the proper specialists, even though the judgment would affect a central chapter of ¢ibādah (i.e., the bāb of fasting). On referring each problem to its rightful subject area, al-Nawawī was following the advice first dispensed by al-Ghazālī more than a century earlier.

In sharp contrast, many contemporary Muslim religious leaders active in the public sphere pontificate about modernity, postmodernity, and other ideological and ideational constructs without having gone through the requisite training. In the absence of that training, engaging different modern philosophical paradigms may take place—but often from populist, identity-driven standpoints. As a result, the intellectual universes that give rise to such issues in the first place are not particularly well examined nor especially well understood. Often this results in alignments with figures on the conservative (and anti-Muslim) right wing of Western political discourse, under the mistaken assumption such figures are allies against these paradigms. With proper training, however, such interlocutors would be proficient, educationally speaking, at advanced levels, about those constructs. Although without requisite training, critics of ideas and ideologies often engage in emotionally driven exercises that lack the rigor exemplified by the likes of al-Ghazālī or al-Muĥāsibī.

The Way Forward

Just as there are premodern problems, there are premodern solutions we are advised to learn from. For example, al-Ghazālī himself was clear that to address the problems of his own age, one had to hold to a normative orthodoxy that remained aware of the need for specialist expertise. More broadly, without a fundamental deconstruction of the issues first, no genuine reconstruction project (what S.M. Naquib al-Attas referred to as “Islamisation” earlier in the twentieth century) was possible. Needless to say, al-Attas’s concept of Islamisation differed quite tremendously from that found in popular parlance later on.

Any deconstruction, as al-Ghazālī showed, first requires deep acquaintance and knowledge of the issue at hand. To give but one example of this: discussions about “Islamic governance” and the idealistic “Islamic state” rarely deconstruct contemporary nation-state dynamics at all—let alone identify how the modern state is rooted in Westphalian ideas of governance. Rather, much if not most of the existing nation-state frames of governance are kept intact while (unsuccessfully) “Islamicized.” Such attempts at pseudo-Islamisation uphold the structure (or grammar) of modern ideas or forms but simply present them in an Islamic vocabulary.

Ironically, an academic who is not Muslim—Columbia University’s Wael Hallaq—identified this kind of failing in much of modern Muslim discourse, which he did succinctly in The Impossible State and also in Rethinking Orientalism. The reasons for this vary but are fundamentally rooted in the failure of postcolonial nation states in Muslim majority countries to reconstruct educational systems that are genuinely critical of some aspects of their own classical heritage but also of intellectual frames imported from Western paradigms. A genuine Islamisation project must deconstruct the “common wisdom” that recognizes modernity as the rightful hegemonic choice and also must critically appraise the Islamic tradition in order to establish rooted, but beautiful, cognitive frames, to borrow a reading from American scholar Umar Faruq Abd-Allah.