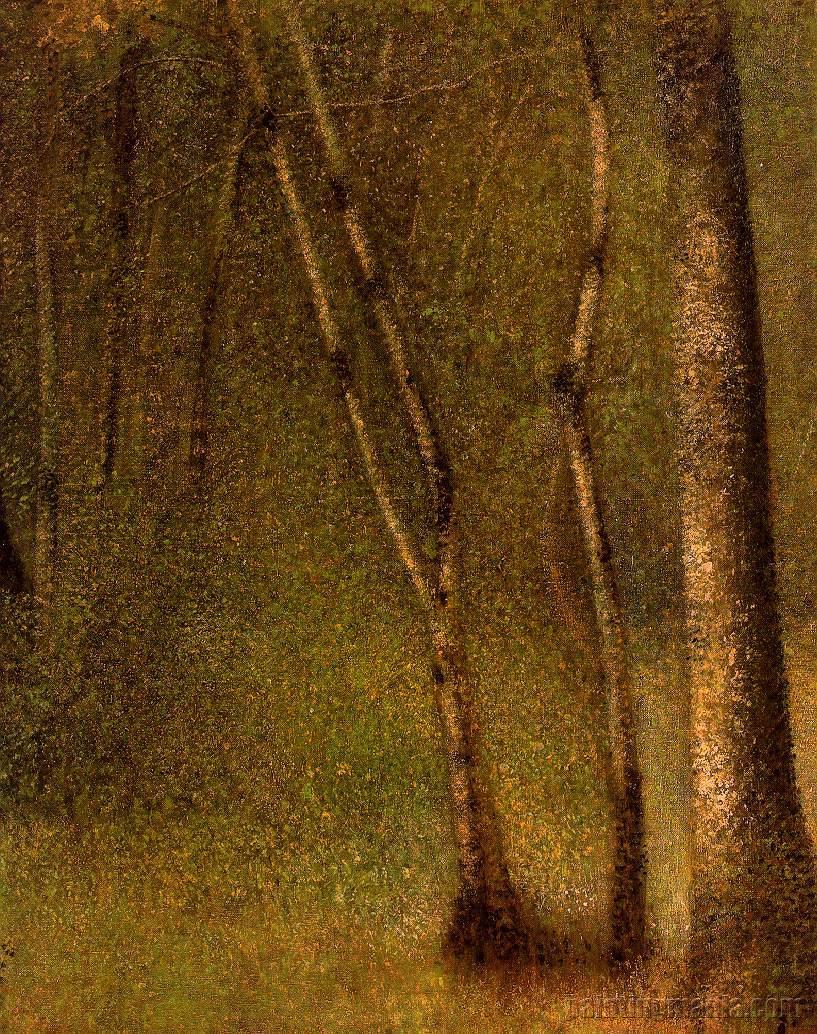

In the Woods at Pontaubert, Georges Seurat

I

There are many kinds of silence. There is a silence of intolerable absence and one of overwhelming presence, a silence of unspeakable remoteness and one of ineffable intimacy, a silence of total ignorance and one of perfect knowledge; and then there are silences of which we are blithely unaware and others of which we are all too keenly conscious. And it is in all these senses, and many others beside, that we may speak about the silence of God—but only so long as we proceed cautiously. All the great religious traditions, after all, as a matter of doctrine, assert that God is not silent, and that He speaks to His creatures in many and various ways. His voice is audible, we are told, in the thunderous deliverances of Sinai, in the eternal “Word” (Logos) of the person of Christ, in the eternal words of the Qur’an, in the ageless utterances of the Vedas and the dictates of the sanātana dharma, in the oracles of the Guru Granth Sahib, and so forth. It is audible also, so all these traditions teach, in the sting of conscience, even if only as an echo reaching us from somewhere we cannot identify. Moreover, all the traditions agree that we hear and see God’s universal self-declaration in His creation: all things are manifestations of the one who makes them, divine words that tell—by their very being, form, and splendor—of God’s omnipotence and glory. In one sense, then, God’s “silence” is only another name for the sheer infinity of the divine eloquence. For it would be a kind of idolatry to imagine that, amid the prodigious polyphony of creation, divine speech should as a rule be discernible as just one small, singular, finite locution among others. Everything all at once is God’s voice. At times, God may speak in articulate language out of the whirlwind, and we long to hear Him do so—revealing, vindicating, explaining, consoling. But, even when He does not, the whirlwind itself is already God speaking.

At the same time, it would be more idolatrous still to mistake God’s address to His creatures in creation and revelation for something like an exhaustive disclosure of the truth of who He is, one that we can formulate in words of our own. There is always that greater mystery that lies beyond all speech, that we can hear—or rather, listen for—only by learning to fall silent. The “apophatic” strictures on the language we use with regard to God, the “negating” predications on which all the great traditions insist, forbid us the presumption of thinking that our ideas or utterances could ever comprehend or express the divine nature in its transcendence. They remind us that even the entirety of creation falls infinitely short of the divine plenitude of being from which it comes. We learn to relinquish the images and symbols and simple notions upon which at first, and for a long time, we naturally rely when seeking to understand who God is, in order to reach the higher and fuller knowledge that awaits us on the far side of those images and symbols and notions. The ultimate and highest end possible for any soul—so say Maximus the Confessor, Ibn ¢Arabī, Ramanuja, and countless other contemplatives—is that “embrace” or “kiss” of union with God in love, in which words and concepts have no place at all because they have been entirely overwhelmed and vanquished by the immediacy of God’s infinite beauty. And even then God still infinitely exceeds all the soul can understand.

In all these senses, God’s “silence” is a kind of perfect and limitless divine harmony, one that cannot be reduced to the sort of language we are able to speak or the sort of songs we are capable of singing.

There is, however, another kind of silence, which is not a blessing (except, perhaps, providentially) but a curse. This is the state of Godforsakenness, the sense of being abandoned by God because one has abandoned Him. It is the failure to hear God speak in anything, in any register—neither in the vast majesty of creation nor in the secret places of the heart nor, for that matter, anywhere at all. This is the silence of despair, and it is induced by our own failure or refusal to hear, and by the universal alienation of the world we live in from God. Here we dwell outside the garden, or outside the gate of the enduring city, or outside the veil of maya. It is a world in which the forces that drive history onward are not, as a rule, divine justice, mercy, and love, but rather violence, cruelty, ambition, and deceit. In such a world, it is quite often the case that we can hear God’s voice only indirectly, precisely to the degree that we make our own words and actions vehicles of His truth. As often as not, what reveals God to us are our own attempts faithfully to express, by our lives and our confessions, the holiness of the divine. In part, so every sound tradition tells us, this means that something of God’s address to us becomes audible, to ourselves and others, when we observe the simple practice of always telling the truth. Simply by speaking of what is as it is—simply by making our words faithfully mirror what is objectively the case—we bear witness to God’s command that our hearts and tongues remain pure, so that we may love and confess Him without profaning His holiness. This seems obvious, and largely unproblematic.

For me, though, perhaps due to some perversity of temperament, this seemingly obvious rule is fraught with all kinds of painful ambiguities. What precisely does it mean always to tell the truth in a world that strives to resist the divine presence? Is it, in fact, clearly the case that fidelity to the truth consists in fidelity to facts, even when the facts that surround us—the facts of history, the facts of an evil situation—are in reality forms of what we might (for want of a more satisfactory term) call ontological falsehood? I am not trying to be precious or elliptical in phrasing the matter thus. In a very real sense, I am raising one of the oldest questions of moral reasoning. Is it possible that there are times when our words more faithfully reflect God’s truth because they do not conform or correspond to what happens to be the case? And by this, I do not mean those times when we merely speak hopefully of things that might be but that are not yet the case; I mean also those times when, out of a love of God’s truth, we might feel compelled to deceive.

II

Is prudence the enemy of virtue or its necessary condition? In a sense, I suppose, this is already a prudential question since every moral decision in life entails both some kind of general adherence to an abstract ethical principle and some kind of particular concrete practical judgment. And even this distinction between universal principles and their prudential applications is only a relative one. We exercise moral prudence only because we believe we are morally obliged to do so—in the abstract and absolutely—since nothing but this obligation compels us to fit our actions to the ethical requirements of the present; yet we embrace universal ethical maxims only in light of their possible consequences since there can be no other way of determining—in the abstract and absolutely—which actions are virtuous rather than vicious. And at either pole of the antithesis (if that is what it is), the same insidious ethical danger threatens. Where morality is concerned, either too deontological a purism or too consequentialist a pragmatism can convert a sound moral axiom into a counsel of moral idiocy. At least it seems correct to say that all ethical life consists in obedience to the correct maxim at the correct moment under a certain set of particular circumstances, in the knowledge that those circumstances play a substantial role in determining the character of that action. It is no doubt right to believe that one should not, as a rule, forcibly prevent a stranger from walking home; but this rule does not forbid us from physically restraining a blind and deaf woman from stepping in front of a speeding car. In that situation, we know that some other moral maxim must take precedence. Prudence without virtue is empty; virtue without prudence is blind. Again, this seems obvious.

And yet something still appears to be unsatisfactory here. On the one hand, it seems pointless to think of ethical commitments as anything other than universal principles of action; on the other hand, it seems foolish to imagine we can behave ethically other than by way of particular acts of commonsense deliberation. And, at least at the present moment in the history of ethical reflection, this constitutes something of a tension. Modern Western ethics in particular, at least since the time of Kant, has been haunted by the exquisite lucidity of his “categorical imperative.” The angels of Königsberg persistently whisper in our ears that an action cannot be truly morally good unless its implicit principle could also serve as a universal maxim of behavior in every possible situation. But in the moment of decision, even the determination of which aspect of our actions constitutes their functional “principle” is a prudential labor of interpretation. And this seems to leave us without a rule of action any more precise than, say, dilige et quod vis fac (to quote Augustine, that notorious relativist)—“Love, then do as you will.” What is the poor ethicist to do? Nor is the dilemma exclusively a modern one. True, it was Kant who propounded a deontological ethics so severe and pure that it would prevent one from telling a lie even if one believed that telling the truth might result in the death of an innocent person at the hands of a violent criminal. In that very claim, of course, lies a contradiction, since the reasons Kant gave for the prohibition on lying—that it undermines the rational dignity of other persons and would render social life impossible if translated into a universal maxim of action—show that even the categorical imperative must ground itself in a consequentialist calculus. Kant, however, need not concern us here.

Snow storm—Steamboat off a Harbour's Mouth, J. M. W. Turner

On this score, he was no more unyielding than, say, Augustine or Thomas Aquinas, and their reasoning on the matter was far more impeccably consistent. For them, simply enough, God is Truth and so—if we are to attune our minds, wills, and actions to God and to dwell in His living presence—we must never violate the truth with our words. What we say must correspond to the objective “facts of the matter,” regardless of the situation. Thus, modern Augustinians and Thomists are every bit as inflexible as any Kantian could ever be on this score. They will tell you that if, say, you were living in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam in 1944, and you knew that Anne Frank, her family, and other Jewish fugitives were hiding in a concealed room behind some bookcases in the Achterhuis down the road, and the Nazis came to your door and asked if in fact Jewish fugitives might be found in that building, you would be absolutely obliged not to lie. Perhaps you might hold your tongue—which would, of course, be the same thing as admitting to your visitors that their suspicions were correct—but you must not in any way willingly mislead anybody. I have even heard one Thomist argue that, in such a situation, one would certainly be allowed to kill the Nazis at the door in order to save the Jewish families down the road, but one must never deceive them. Now, certainly, I would never want to dissuade anyone from killing Nazis, if that should be the only way to prevent them from doing the sorts of things Nazis do; I am no pacifist. But, for argument’s sake, let us assume that this option does not exist. You are ninety years old, confined to a wheelchair, unarmed, and all alone. Indeed, while we are at it, we might as well add that you are blind and manacled to your chair. Even then, so warns the Thomist—or the Augustinian, no less than the Kantian—you must never tell a lie. God (like the categorical imperative) can be served only by betraying the Jewish families hiding in the Achterhuis to those who would murder them.

I do not actually believe that anyone really believes this. I know, however, that a certain number of ethicists and theologians believe they believe it, and this troubles me. I am honestly convinced that, in that situation, one would not tell the truth—in fact, one would not fail to lie—except out of either cowardice or malice, even if one were able to convince oneself afterward that one’s motives were really purely moral. One’s ability just then to “obey,” with a clear conscience, the absolute prohibition on lying to others would be dependent on one’s skill at lying to oneself. That, however, is not my principal concern here. Rather, what interests me is the curiously questionable logic of insisting on any inviolable moral maxim of truthfulness in a world in as much (so to speak) transcendental disarray as ours. Only in a world where prudence is never required, because contradictions cannot arise between what we ought to desire and what the world really is, can it possibly be the case that telling the truth—in the barren and perhaps dubious sense of simply reporting whatever happens to be factually the case, careful to make sure that one’s words correspond in an altogether atomistic fashion to each of the discrete particular features of those facts—is a moral good in and of itself. It is strange enough that modern philosophers should so utterly dissociate ethics from epistemology, as specific spheres of inquiry, that they can discuss the ethical status of lying in total abstraction from a deeper consideration of precisely what truth itself might be and so can assume a virtual identity between truthfulness and factuality. It is almost absurd to see champions of antique or mediaeval systems of moral reasoning falling prey to the same omission. I say this for metaphysical reasons, but those reasons have moral implications. I accept the premise (as any believer in transcendent truth must) that we must never violate the truth with our words. I simply suspect that classical theists are logically bound to believe that our words can often preserve truth’s inviolability only when they mislead—only, that is, when they silence history’s silencing of God’s voice.

III

I assume, to begin with, that practically everyone can recognize that truth-telling and lying are actions that admit of differing modalities. For instance, I assume that most ethicists—Kantian, Christian, Jewish, Muslim, religious of every variety—would grant that there is no moral requirement that one’s words correspond to any actual set of facts when one is engaged in writing fiction. A novelist who at no point in his or her text gives any indication that the events in the novel did not actually take place in the physical world we all share is not guilty of a sin, surely. And yet, in a very real sense, in keeping with the conventions and necessities of the particular virtuous action in which he or she is engaged—the action, that is, of creating a work of art—he or she is in some sense telling lies, or at least not making his or her words conform to any actual state of affairs. Nevertheless, we all grant that there is another kind of truth, and perhaps at times a much higher one, appropriate to fiction. In fact, most of us would grant, I hope, that a truly great writer can often reveal more of truth, in a higher sense, than any mere factual accounting of real events could ever do, precisely because that truth is rarely if ever fully embodied in quotidian events. The true, in this case, is something essentially contrary to the merely factual. But surely, then, this is not merely a matter of aesthetic license, without moral meaning. How could it be? How could the writing of fiction ever be a virtuous act if we cannot concede both that truth and fact are conceptually and ontologically distinct, and that at times our words can serve the former only by taking leave of the latter?

Detail of Contemporary Terracotta Warriors, Yue Minjun

So, then, to quote a prominent figure from Christian scripture: What is truth? For a Christian, of course, as for a Jew, Muslim, virtuous pagan, Hindu, Sikh, or any other adherent to the most venerable classical metaphysical claims, truth in the fullest sense—like goodness and beauty—is an eternal transcendent reality, originally and ultimately convertible with being itself, and completely coinciding with all other transcendental predicates in its divine source and end. In God, the true, good, and beautiful are all one and the same splendor of the real, one-and-the-same perfect act of being. Truth, before all else, and certainly before it becomes a matter of some epistemologically measurable correspondence between words and facts, is an ontological perfection, and hence one of the names of God. And so, yes, one must remain faithful to truth, but one must also remain faithful to all the transcendentals, all the perfections of being in its holiness, at the same time. And this creates something of a problem. If we dwelled in paradise, in an unfallen world, in Eden, or if we had already come to the end of the tale, in the final reality of a restored creation, in the Kingdom or the Garden or the Age to Come or Vaikun.ţha or the Western Pure Land, beyond every shadow of sin and death, then we would never have to choose between the good and the beautiful, the beautiful and the true, the true and the good. There would be no separation of the ethical from the epistemic, the epistemic from the aesthetic, the aesthetic from the ethical, and certainly no conflicts among them. There would be only one order of desire—the rational soul’s longing for God, a single pure movement of the mind and heart toward the one true terminus of every rational and virtuous longing. Ethics would not exist; neither would aesthetics or epistemology. There would be only love for the irresistibly desirable.

In the world we actually inhabit, however, the simple light of being’s splendor has been refracted into separate and at times incompatible modes of the real. The divine light in its purity and immediacy lies now on the other side of the prism of created being in its fallen or deluded condition, and for the most part we know that light as, at best, a scattered iridescence. Ideally, we should live lives in which the good, true, and beautiful are as nearly reintegrated into a single style of existence as possible; but the ideal is rarely attainable. From moment to moment, we are confronted by conflicting transcendental vocations, and moral prudence consists in nothing other than choosing which among them must, in any given instant, assume the station of the dominant value. An artist in the moment of creation must for the most part obey the beautiful above all. A reporter seeking to expose government corruption must seek the true before anything else. And an invalid in Amsterdam in 1944, visited by Nazis who are looking for Jewish families, must not allow any value but the good to dictate his or her words and actions. Admittedly, it is never the case that any transcendental value reveals itself in absolute isolation from all others; where the good is present, so also in some measure are the beautiful and true, and so on for each of them. And each is more itself the more perfectly it coincides in actuality with each of the others but is more spectrally removed from its proper essence the more dissociated it becomes from each of the others. The more distinct these transcendental perfections become, as different modes of being—ens qua bonum, ens qua verum, ens qua pulchrum, et cetera—the less fully they express the splendor of being. Even so, it is also almost always the case that we must determine which of the transcendental perfections we should assign the highest station in the hierarchy of values at any given moment in order to allow us to be as faithful as possible to all of them together in their divine reality. Sometimes we must isolate a single dimension of being as our supreme object of concern because it is the aspect of God’s reality that makes the greatest claim upon us in that moment. Only by a prudential ordering of ends in a hierarchy of relative priority can we, in any instant, remain faithful to all the proper ends of our nature. So there are times when, say, a dedication to the good must in some way inhibit a dedication to truth, or at least qualify it under the form of a dissimulation, precisely so that we can serve truth (which is also goodness) as such. Sometimes, if we are devoted to truth, we must deceive.

After all, if truth is most essentially an ontological reality—a name for being, and so for God—then it cannot simply be a matter of a correspondence between words and facts. In a fallen reality, there are times when the facts of the matter are ontological untruths, because they are privations of the good. And if, moreover, we define truth as a name for being, and we define being as pure actuality rather than as, say, some kind of Fregean second-order proposition about what general possibilities are instantiated in which particular facts, then we must also grant that truth is present to the degree that it is made manifest in substantial forms and specific orderings of events; it is something to be desired as a transcendental end in itself, convertible with goodness and beauty and so forth, which like any such end inspires an incalculable variety of practices. At least, we must never confuse ontological perfections for personal styles of behavior. It is the substance we should seek, not some maxim for our behavior that would be equally valid whether or not it can lead to that concrete and objective reality. Just as pacifism is not peace, but merely a form of personal comportment that may serve either peace or conflict (as the case may be), so reporting facts is not truth but merely a use of signs that may serve either truth or (ontological) falsehood. Thus, when the Nazis come for Anne Frank and her fellow Jews in hiding, we can make our words faithful either to divine truth or to an objectively disordered state of affairs that is contrary to truth in its essence, but we cannot make them faithful to both. As I have said, the more starkly these transcendental predicates are alienated from one another in actuality, the less any one of them is itself. All evil is a privation, after all, the distortion of a substantial good. A certain concern for the facts may arise from a devotion to truth; but sometimes facts are the lies this world tells about the true nature of reality, and so to speak those facts is to serve the father of lies rather than God.

Vesuvius in Eruption, J.M.W. Turner, circa 1817

IV

Dilige et quod vis fac. Perhaps, after all, Augustine’s maxim turns out to be the only real categorical imperative for someone who believes in the coincidence of being’s perfections in the simplicity of God. Ethics, conceived as a science, can quickly become a demonic nonsense. How could it not, after all, since ethics as a discrete sphere of concern exists only by virtue of our loss of paradise and our exile in the shadow realm of human history? Ethical theory—or better, moral theology—serves a good end only if we understand it as something we pursue in order to correct the deficiencies of our love and the injustices of fallen time. It must flow from and, in the end, yield itself up to a spiritual attentiveness to the voice of God in the moment, as it breaks through the silence of this world’s seeming Godforsakenness. Perhaps all this is obvious. But it seems worth saying anyway, as clearly as possible, even if most of us already know it as a practical truth. To dwell in mere human history in this world—to dwell exclusively in facts—is also often to dwell in untruth. And so the law of love is not merely some inflexible ethical rule we rely upon to negotiate the contingencies of that history. Rather, it is a kind of anarchic escape from all such rules into a realm of direct responsibility before reality in its transcendent plenitude. It is a devotion not to any abstract maxim but to a living divine word that comes always as revelation, a novum breaking in upon our expectations and demanding a response that cannot be reduced to a mere axiom. It is the will to shatter the silence that history would impose upon the voice of God.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy