And We will indeed test you with something of fear and hunger, and loss of wealth, souls, and fruits; and give glad tidings to the patient—those who, when affliction befalls them, say, “Truly we are God’s and unto Him we return.” They are those upon whom come the blessings from their Lord, and compassion, and they are those who are rightly guided. (Qur’an 2:155–157)

The Qur’an is replete with verses concerning the nature of the world, including its trials and tribulations, as if the Qur’an, through these verses, wants to prepare us to expect adversities and afflictions that will shake us from the heedless sleep of our daily uneventful routines. Our expectations determine our responses to the suffering we encounter during our life on earth, and our understanding of the reality of this world and our surrender to the reality of God determine our expectations of this world.

In the verse above, when God says, “And We will indeed test you” (wa la-nabluwannakum), it is actually an announcement—what commentators have termed a forewarning (indhār). The Arab proverb “Whoever forewarns has given his excuse” (man andhara a¢dhara) seems to fit. Thus, we should expect what we are being warned about: myriad misfortunes will surely afflict us in our lifetimes. Tribulation (balā’) is at the heart of life, and the Qur’an tells us that God, the exalted, will test us.

The first test regards fear. Fear is universal, a natural occurrence of our human condition; in fact, the first emotion a child experiences coming into the world is fear—hence the terrified look and the shrieks of fear from the newborn until the mother embraces the child in the breast of security. Throughout life, we all experience fear: the fear of losing a job, the fear of a loved one dying, the fear of failure on a test or in a commercial enterprise. Even the prophets, who were indeed courageous, had fear: for instance, the Qur’an says that Moses, peace be upon him, actually felt fear in his heart (20:67). Fear protects us from foolhardiness and folly. Indeed, as Alexander Pope famously said, “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” Courage is not the absence of fear but an attribute that allows us to overcome disabling fear, which can incapacitate us from acting appropriately when faced with trials: the firefighter who rushes into a burning building to save people has a courage that overrides the fear of harm.

As the verse continues, God says that we will be tested with hunger (al-jū¢). Given that we live in an age of cornucopia, with an abundance of foods and riches, especially in much of the Western world, we often forget that the premodern world, prior to the industrial farming and husbandry that exist today, often experienced periods of depleted resources and even famine. Oddly, amidst the opulence of modern societies, we also witness a paucity of gratitude: we forget that hunger is still a pervasive part of the modern world.

Traditional civilizations had a culture of thanksgiving—of saying grace before eating the food on the plate before them and offering a hearty “al-ĥamdu lillāh” upon finishing it. In some Arab cultures, people would say, “Clean up Medina” (nażżifū al-Madīnah), meaning “Finish eating all that’s on your plate”; in some South Asian cultures, children are told that if they finish the food on their plates, they will receive the same reward as those who clean the Kaaba. Such gratitude can be traced back to the Prophet ﷺ, who had high esteem for the blessings of God. His companions reported that he never complained of food; if he liked it, he ate it, and if not, he refrained from it without comment. Fasting, intrinsic to all major religions, facilitates an appreciation for the gift of food when people break their fasts; Muslims, who fast during daylight hours in the month of Ramadan, get a taste of hunger, a palpable physical sensation, which engenders gratitude for the blessing of food but also cultivates empathy for those for whom hunger is the norm.

Man praying in Nakhoda Masjid, the principal mosque of Kolkata, India; photo: Chitragrapher / Wikimedia Commons

The verse continues by saying that God will test us with the “loss of wealth, souls, and fruits” (wa naqśin min al-amwāli wa al-anfusi wa al-thamarāt). The Arabic word naqś has many meanings, one of which is loss or diminution. We will be tested with the loss or lessening of wealth as well as the loss or diminishment of life: people lose their memory, eyesight, hearing, limbs, loved ones, friends, pets, and so on—all of which we take for granted until they’re gone. No life remains exempt. That loss lies at the root of the nature of this abode, and much wisdom can be gained by embracing the losses we experience along the way. As Shakespeare wrote, “Let me embrace thee, sour adversity, for wise men say it is the wisest course.”

The Qur’anic verse then turns to the matter of how we should understand and consequently respond to the tests of fear, hunger, and loss of wealth, life, and fruits: “Give glad tidings to the patient ones” (wa bashshir al-śābirīn)—that is, those who are patient in the tribulation. During times of adversity, many struggle hard to be patient. Real patience, as understood in the Islamic tradition, means “to be patient in your obedience and patient in refraining from disobedience” (al-śabr ¢alā al-ţā¢ah wa al-śabr ¢an al-ma¢āśī)—to hold yourself back when you begin to lose patience and fall into despair. St. Thomas Aquinas considered placing patience among the principle virtues because the Epistle of James states that “patience has its perfect work.” However, like the Muslim virtue ethicists before him, Aquinas considered it to be a “daughter” of the four cardinal virtues. The virtues of both courage and temperance “give birth” to patience, which allows one to bear a burden and to be steadfast in trials: a soldier shows patience and steadfastness through courage in overcoming fears on the battlefield. A temperate person exhibits steadfastness and patience in resisting temptations. So “the patient ones” in the Qur’anic verse are those who maintain steadfastness in their obedience to their creator.

In his essay “A Dangerous Schooling: How Suffering Educates Us for Eternity,” Kierkegaard quotes Hebrews 5:8, which says that “Jesus learned obedience from what he suffered.” According to Kierkegaard, learning obedience from suffering does not come easily, but if a man fails to learn obedience, “then he may learn what is most corrupting: to learn craven despondency, learn to quench the spirit, learn to deaden any noble fervor in it, learn defiance and despair” (see page 1 in this journal). When tribulation comes, and when we learn obedience from it, Kierkegaard says, we are being educated for eternity. When we are patient in obedience and patient in avoiding sinfulness, then sin, sorrow, self-absorption, and self-pity, which blind us to the good hidden in the trial, do not create an impatient hankering in our soul that blinds us to the good.

In the Islamic tradition, tribulation (ibtilā’) is the guardian angel that keeps us from slipping into the heedlessness and fragmentariness of the world, which can rip apart our souls. Only suffering keeps us in school—this “dangerous schooling,” as Kierkegaard refers to it. If we have patience in tribulation and gratitude in blessing, we are vertically aligned with God. If, however, we fail to raise our eyes to the heavens and remain horizontally aligned with the world, then desperation inevitably overwhelms our understanding and leads us to the depths of despair.

Unfortunately, a thoroughly modern and increasingly common phenomenon is the lament of complaint, a self-obsessed why-is-this-happening-to-me response to tribulation, something that was uncommon in premodern societies and remains rare in the vestiges of traditional cultures today. Decades ago, when I lived in Mauritania, many assumed I was a Westerner who knew medicine, so they would often describe their ailments to me in hopes that I could help. What struck me is they always framed their descriptions with statements such as, “I’m just explaining what I’m experiencing to you” (Hādhā ¢arđ ĥāl); “I’m not complaining: praise and gratitude is God’s alone” (Laysa shakwā: al-ĥamdu lillāh wa al-shukru lillāh). What lies beneath that impulse is a profound yet simple belief that we, in essence, belong to God, and hence our bodies and our souls are God’s dominion.

About those who are patient during tribulation, the Qur’anic verse says, “When affliction befalls them (alladhīna idhā aśābathum muśībah), they say, ‘Truly we are God’s and unto Him we return’ (innā lillāhi wa innā ilayhi rāji¢ūn).” We, as God’s creation, belong solely to God, and He can do with us whatever He pleases. Elsewhere, the Qur’an says, “No calamity afflicts you except that it is from God” (64:11); another verse says, “except it is from your own selves” (4:79). Nevertheless, these two verses are not seen as contradictory because even though everything is from God, the exalted, our comportment (adab) with God is to blame the self when ill afflicts us. Many of our ills arise directly from our poor stewardship of God’s property: we often neglect our bodies, eat unhealthy foods, fail to exercise, and then call upon God plaintively to heal us. However, if we are righteous, pious servants of the Merciful and steward well our lives but still are stricken with calamities, then these are trials from God, and we must surrender to Him. About those who surrender and do not ask “Why me?” God says, “They are those upon whom come the blessings from their Lord, and compassion.” God blesses them because they are in a state of patience, which is really a state of gratitude in that they recognize that everything is from God, including the calamity, and therefore it too must be good.

***

The mystery of iniquity remains one of life’s greatest challenges, one that has perplexed philosophers and poets since time immemorial. They have grappled with this mystery and often offered guidance that exalts the revealed truths received from the prophets. In Moby Dick, in a chapter entitled “The Gilder,” Melville reveals that we have essentially three responses to the mystery of iniquity: that of Captain Ahab or of one of his two crew members, Starbuck and Stubb. Each of us will choose one of these responses.

In this excerpt, Melville describes the aftermath of the long stretches of sailing and paddling on the ship at sea, when Ahab and the crew are finally resting and relaxing, in pleasant weather, with nothing but the openness of the ocean all around them, and how differently each reacts to the scene of grandeur and grace:

Under an abated sun; afloat all day upon smooth, slow heaving swells; seated in his boat, light as a birch canoe; and so sociably mixing with the soft waves themselves, that like hearth-stone cats they purr against the gunwale; these are the times of dreamy quietude, when beholding the tranquil beauty and brilliancy of the ocean’s skin, one forgets the tiger heart that pants beneath it; and would not willingly remember, that this velvet paw but conceals a remorseless fang.

These are the times, when in his whale-boat the rover softly feels a certain filial, confident, land-like feeling towards the sea; that he regards it as so much flowery earth; and the distant ship revealing only the tops of her masts, seems struggling forward, not through high rolling waves, but through the tall grass of a rolling prairie: as when the western emigrants’ horses only show their erected ears, while their hidden bodies widely wade through the amazing verdure.

The long-drawn virgin vales; the mild blue hill-sides; as over these there steals the hush, the hum; you almost swear that play-wearied children lie sleeping in these solitudes, in some glad May-time, when the flowers of the woods are plucked. And all this mixes with your most mystic mood; so that fact and fancy, half-way meeting, interpenetrate, and form one seamless whole.

Nor did such soothing scenes, however temporary, fail of at least as temporary an effect on Ahab. But if these secret golden keys did seem to open in him his own secret golden treasuries, yet did his breath upon them prove but tarnishing.

Oh, grassy glades! oh ever vernal endless landscapes in the soul; in ye,—though long parched by the dead drought of the earthly life,—in ye, men yet may roll, like young horses in new morning clover; and for some few fleeting moments, feel the cool dew of the life immortal on them. Would to God these blessed calms would last. But the mingled, mingling threads of life are woven by warp and woof: calms crossed by storms, a storm for every calm. There is no steady unretracing progress in this life; we do not advance through fixed gradations, and at the last one pause:—through infancy’s unconscious spell, boyhood’s thoughtless faith, adolescence’ doubt (the common doom), then scepticism, then disbelief, resting at last in manhood’s pondering repose of If. But once gone through, we trace the round again; and are infants, boys, and men, and Ifs eternally. Where lies the final harbor, whence we unmoor no more? In what rapt ether sails the world, of which the weariest will never weary? Where is the foundling’s father hidden? Our souls are like those orphans whose unwedded mothers die in bearing them: the secret of our paternity lies in their grave, and we must there to learn it.

And that same day, too, gazing far down from his boat’s side into that same golden sea, Starbuck lowly murmured:—“Loveliness unfathomable, as ever lover saw in his young bride’s eyes!—Tell me not of thy teeth-tiered sharks, and thy kidnapping cannibal ways. Let faith oust fact; let fancy oust memory; I look deep down and do believe.”

And Stubb, fish-like, with sparkling scales, leaped up in that same golden light:—

“I am Stubb, and Stubb has his history; but here Stubb takes oaths that he has always been jolly!”

In the reactions of these three mythic characters to the awe-inspiring panorama of the sea in golden light, Melville captures, rather neatly, the totality of human responses to the exquisite beauty of the natural world. Ahab, the conflicted skeptic, could believe in an unseen creator if his days were always as glorious as the calm, serene, and irenic one he is experiencing as he looks out at the vast, expansive, and settled ocean. But the terrible trials of the world—not the least of them being the loss of his leg to a giant whale that made him succumb to this revenge quest—infuse his mind with doubt and obsession. Faith, in Ahab’s sardonic mind, represents the innocence of a schoolboy who will later confront life’s tragic realities. His response resembles that of Shakespeare’s Hamlet in his early phase (Melville knew the play all too well), when Hamlet questions life’s meaning or its meaninglessness in his famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy. Yet, unlike Hamlet, who resolves his crisis by the end of the play with his understanding that “the readiness is all,” Ahab remains the inveterate skeptic.

Ottoman capitulation at Nikopol in Russo-Turkish War, Nikolai Dmitriev-Orenburgsky, 1883

Starbuck, like Hamlet in his final phase, looks at the same ocean as his captain, and despite the gales, storms, and squalls of life, he chooses to believe. He recognizes something deeper than the disruptions and distractions of life on earth. In the glorious beauty and majesty of the creative act, the doubts and the troubling facts from his life experiences that threaten his faith recede, and he lets “faith oust fact,” enabling him to see the providential hand at work.

And finally, we have the Stubbs of this world, those who are imprisoned by their egos, are incapable of much beside the pursuit of momentary pleasures, and see no meaning beyond the material world, nothing larger than their own lives. Stubb is the lowly, contemptible narcissist who lives only for himself: fishlike with his sparkling scales, he declares, “I am Stubb,” living his piscine existence akin to the bovine one lived by landlubbers.

These three modes of being align well with the three types of people mentioned at the outset of the second chapter of the Qur’an, from which the opening verses of this essay are taken: the disbeliever (Stubb), which God describes in only two verses; the believer (Starbuck), which God describes in just four verses; and the skeptic, the oscillator, who wavers between belief and disbelief (Ahab), which God describes in thirteen verses. The proportion of words Melville uses to describe each of these three characters is strikingly similar to the proportion of words God uses to describe the three archetypes.

In Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the four brothers grapple with the same problem: the mystery of iniquity. After Ivan’s nihilistic philosophy is acted out by his student Smerdyakov, Ivan realizes the tragic truth of a world without God. Hence, iniquity, the very concept, becomes the greatest proof for God’s existence: for moral goodness that determines iniquity in the first place can exist only if there is a God. Dostoevsky returns to this theme again and again. For the believer, the iniquities of the world are resolved with an understanding of the nature of the world, as Emily Dickenson reminds us: “The world is not conclusion. / A species stands beyond / invisible as music / but positive as sound.” The iniquities of the world only make sense when one realizes the world is not conclusion: a day is coming when the debts will fall due. When doomsday arrives, every dog will have his day, and every man and woman too.

For this reason, the believer sees all the events of the world as good because they are actualized creations of God. Their moral dimension—the chain of events that lead up to any event and the chain of events set off by that same event—cannot be grasped by the human intellect. This does not mean that we cannot determine right from wrong: it only means that we cannot judge the event by what we can surmise of the event itself. Rather, we must leave to God the ultimate judgment and trust its goodness because it comes from God. Only God brings forth good from evil, benefit from harm, and life from death. This is why the verses that open this essay end with “They are those who are rightly guided.” They are rightly guided because they understand that the mystery of iniquity cannot be penetrated by our natural intelligence, that a genuflection of our mind (sajdah in the Islamic rendition) to the supernatural intelligence is required. This is not faith without reason: this is reasonable faith infused with a supernatural self-evidence that transcends the evidence of natural life.

In a wonderful hadith related by Śuhayb al-Rūmī in the famous Śaĥīĥ Muslim collection (one of the six canonical imams and a student of Imam al-Bukhārī), the Prophet ﷺ said,

How wonderous is the affair of the believers: verily, all of their affair is good. And that is for no one except the believers. When they are given a blessing, they are grateful, and it [the blessing] was good for them. And if they are afflicted with anything harmful [calamities, diseases, loss of wealth], they show patience. And therefore, it was better for them.

In essence, this hadith expresses the well-known phrase “It’s all good,” a statement of spiritual discernment, and one that is true. A lot of people today, especially in the black American community, say these words to indicate acceptance of tribulations, large or small, acceptance of the metaphysical reality that whatever happened was meant to be: “It’s all good!” The hadith is essentially saying that if you are a believer, it’s all good! Even harm is good because there is wisdom (ĥikmah) behind it that may be unknown to us.

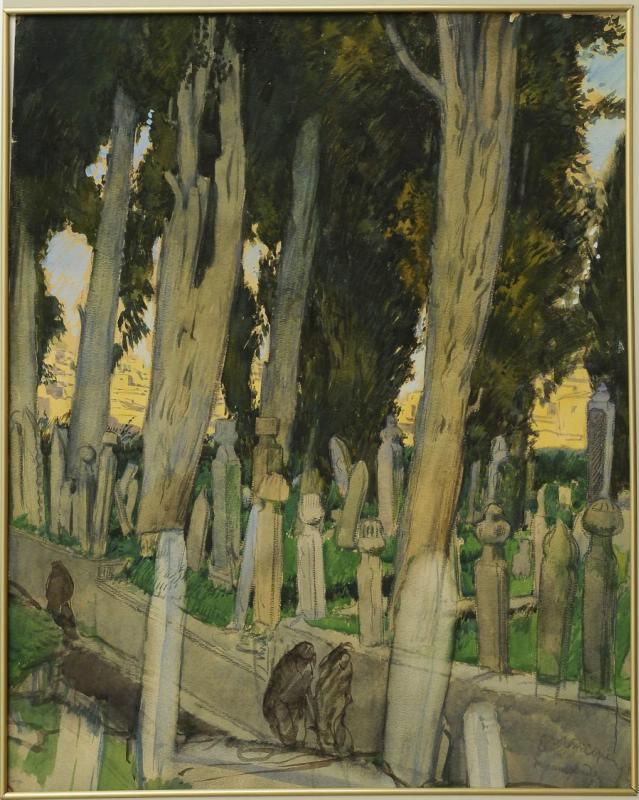

Muslim Cemetery in Ottoman City Trebizond, Evgeny Evgenievich Lancere, 1917

Tribulations are not just difficulties or natural disasters that happen to us, such as the COVID-19 pandemic; as Sidi Aĥmad Zarrūq says, “A person is a tribulation to him or herself,” and we can be tribulations to others. God says, “We have privileged some of you over others, and the afterlife has greater privileges” (17:21). So when we see somebody who is in a privileged state, the relevant question should be this: Are they using their privilege for good or for ill? The Qur’an says, “We made some of you a tribulation for others; will you show patience? And your Lord sees everything” (25:20). About this verse, the fourteenth-century theologian Ibn al-Qayyim al-Jawziyyah said that God has made poor people a tribulation for rich people and rich people a tribulation for poor people; He has made the ignorant a tribulation for the learned and the learned a tribulation for the ignorant; and so on. This is the world that we are in; the ultimate question before us is whether we can accept and, by acceptance, submit to the reality of God, or whether we are going to remain ignorant (jāhilī).

***

The notion that human beings can be a tribulation for other human beings was captured in a secular twentieth-century aphorism, “Hell is other people.” However, this misses the point by far. In his famous fifteenth-century book Qawā¢id al-taśawwuf (The principles of Sufism), Sidi Aĥmad Zarrūq gives the 165th principle: “The uniqueness of God, the most high, in His perfection, determines the establishment of imperfection in anyone other than God.” In other words, God is unique in His perfection, so all else is deficient. Perfection is not inherent in human beings: when we see imperfections, deficiencies, and weaknesses in other people, we are seeing their nature, which, by the fact of their createdness, contains the potentiality of perfection, but only through God’s grace can perfection become a reality. Sidi Aĥmad Zarrūq continues, “So you will not find a perfected one, unless God has perfected him, and he is perfected through the grace of God.” For example, the Prophet’s perfection is from the perfection of God, something that God made out of His bounty (fađl).

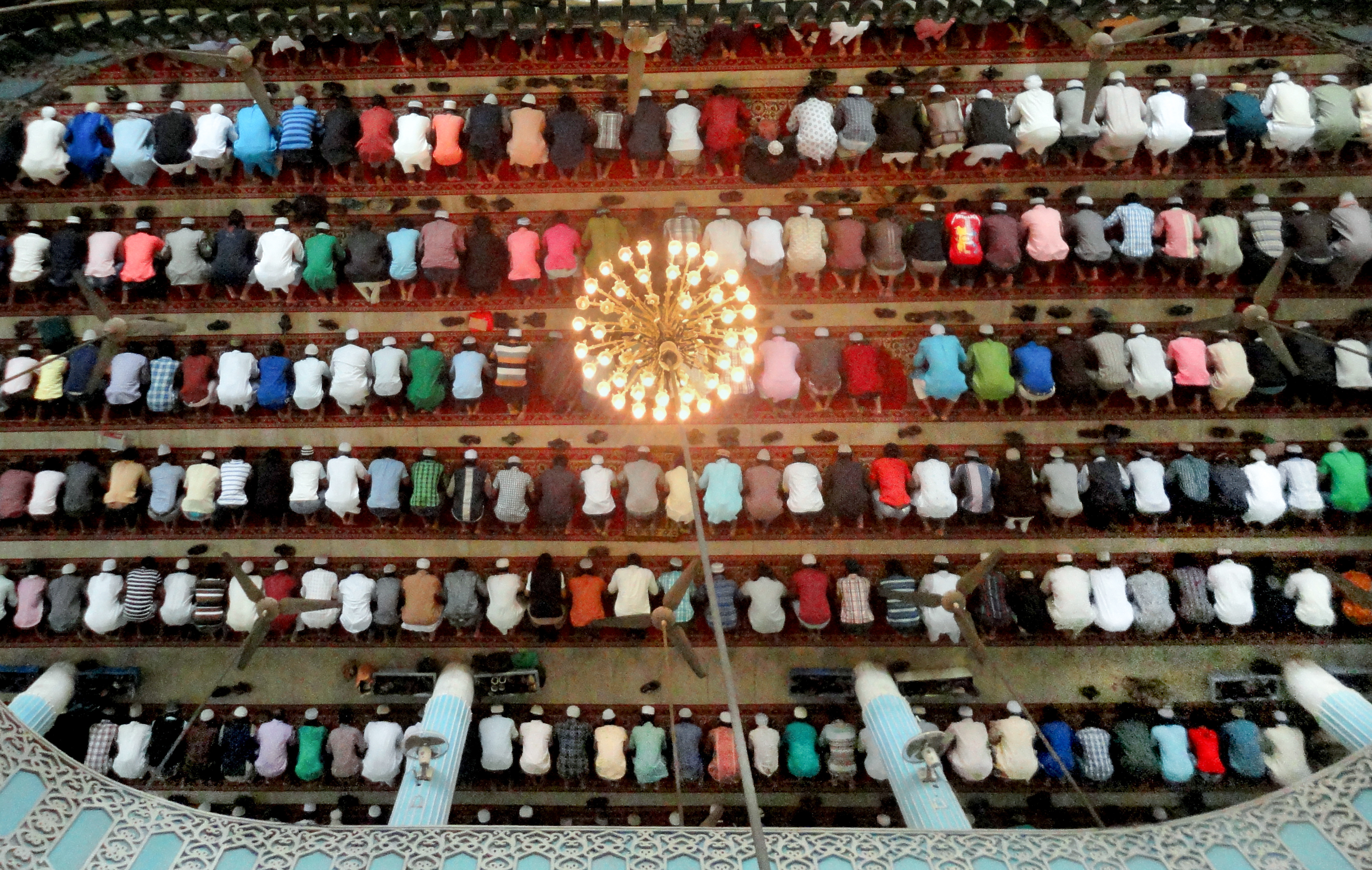

Communal prayer in a mosque in Bangladesh; photo: Shaeekh Shuvro / Flickr

Sidi Aĥmad Zarrūq then says, “To seek perfection in existence based on its foundation of imperfection is vanity.” Hence, it is certainly unwise, if not wrong, to expect one’s spouse or child, let alone institutions, entities, and governments, to be perfect. The perfect world is paradise (jannah). The place we inhabit is called dunyā: it is the lowest place in the universe, a place where we leave behind our foulness by seeking the path of purification: it’s all up from here. Even people in hell are in a state of remembrance of God (dhikr) and repentance of remorse, wishing that they had been righteous and not wasted their lives.

Sidi Aĥmad Zarrūq continues, “Due to this, it has been said to look at creation with the eye of perfection, but consider in their essences imperfection.” In other words, he counsels us to look with Starbuck’s eyes, not those of Ahab or Stubb: this leads to an ability to be kind to people and to have a good opinion of them. “And through that,” he says, “one is able to guard oneself and maintain a good opinion, perpetual conviviality, and a lack of concern about others’ slips or faults.”

Sidi Aĥmad Zarrūq ends his 165th principle with a quotation from Imam al-Junayd, who directly connects our understanding of the imperfections of human beings—and of our world—to a principle that we would do well to heed: “I have taken as an axiom that has enabled me since then to never be disturbed by what afflicts me from this world.” What is this principle, this foundational truth? “And it is this: that the abode of this world is an abode of stress, despondency, tribulation, and strife. And this world—all of it—is wanting (sharr).” While sharr is sometimes understood to mean “evil,” it really refers to “being deficient or wanting.” The Arabs call “poverty” sharr because if we are poor, we lack wealth. This world (dunyā) is an abode of want, about which Imam al-Junayd continues, “Its nature is such that it will confront me with everything I detest, and should it meet me with what I love, it is simply abundant grace. And if not, its nature is as was stated.”

In the Islamic tradition, tribulation (ibtilā’) is the guardian angel that keeps us from slipping into the heedlessness and fragmentariness of the world, which can rip apart our souls.

The world presents us with tribulation, and if we experience times free of such trials in this abode of trials, they come only from God’s grace. Such a worldview aligns well with the first and second of the four noble truths of Buddhism: suffering and insatiability are natural characteristics of existence on earth, and the source of suffering is our craving, our attachment to the world. As Kierkegaard’s essay states, we have to be weaned from the world through suffering, like a child cries as it is weaned from its mother’s breast. The mother’s weaning emanates from an understanding that the child must move on to the next stage of life. In the end, we will be forcibly weaned from this world when we die. In the meantime, growing up means giving up the breast of the world, and suffering enables our detachment from an abode we must depart from, whether we accept it freely with a shout of joy or submit to it remorsefully with a cry of desperation.

We are disheartened and suffer when we have expectations that are not met by the realities of the world and its people. But if we see this world as a place where God will test us with something of fear and hunger, a loss or diminution of wealth and life, and if we are patient with the painful predicaments and are grateful for the bounteous blessings, we will be happier for those choices.

The Prophet ﷺ was always positive and at peace with the abode; that is why the numerous trials and tribulations he went through never affected his spirit. He ﷺ was always in the hub—in the eye of the hurricane. God made the hurricane, but He also made the eye of the hurricane. If we are in the eye of the hurricane, the turbulence swirling around us will not disturb our equanimity. The hurricane is this world (dunyā), but the eye is the otherworldly access that we have as a gift of grace if we choose to see everything, the good and the ill, as emanating from a benevolent, merciful creator. Being in the eye of the hurricane means accepting the world as it is—this tempestuous, monstrous gale of goodness, whose goodness resides in its very act of being—and participating in its fullness, in the effulgent evanescence that is life on earth, with joy. In the brief time allotted to us on this planet, we can discover (literally, uncover) God, who hides in plain sight. This is preparation—the readiness is all—for a return to God. Indeed, with each and every adversity or affliction that befalls us, let us remind ourselves, “Truly we are God’s and unto Him we return.”

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy