A detail of the al-Attarine Madrasa in Morocco; photo by Mike Prince

Knowledge of the Arabic language forever remains foundational and an essential latchkey to unlocking the doors of Islam’s sacred law. Without a deep knowledge of Arabic, students will become confused and lose their way; they will miss the mark and have no firm ground upon which to stand, for the simple reason that the Qur’an came down in “a clear Arabic tongue.” God said, “Truly, this Qur’an has been sent down by the Lord of the Worlds: the Trustworthy Spirit revealed it to your heart [Prophet] so that you could bring warning in a clear Arabic tongue” (26:192– 95). He also said, “So, We have revealed an Arabic Qur’an to you” (42:7), and “We have sent it down as an Arabic Qur’an so that you may understand” (12:2); other verses also indicate the Arabic nature of the Qur’an as well.

It is important to note the distinction between the adjective used (i.e., an “Arabic” Qur’an) as opposed to saying an “Arab” Qur’an. Though the Qur’an was revealed in one geographical area, its application is global. God said, “We have sent you [Prophet] only to bring good news and warning to all people” (34:28). It is therefore not a message that is for some people and not for others, nor is it for one era to the exclusion of other epochs. The Prophet Muĥammad ﷺ said, “A prophet used to be sent to his own ethnic people exclusively, but I was sent to every person, no matter what their color.”1

The final scripture, revealed in Arabic, greatly honors the Arabs. Hence, a great responsibility was placed upon the believers among them to make this religion as clear as possible to people, while being a testament against the disbelievers among them, for the message has reached them in the best possible manner….

This indispensability of the Arabic language to engaging the sources of Islam’s sacred law compelled the early generations to immerse themselves completely in the study of Arabic, dedicating vast and sundry resources to that end. In this regard, history records noteworthy yet intriguing incidents. Ibn Ya¢īsh recorded one such event in his Sharĥ li al-Mufaśśal: the Commander of the Faithful, ¢Umar b. al-Khaţţāb, had received a missive from Abū Mūsā al-Ash¢arī, who served as a judge in Kufa. The missive opened with the phrase “From Abū Mūsā al-Ash¢arī to the Commander of the Faithful (min Abū Mūsā al-Ash¢arī ilā Amīr al-Mu’minīn)” with Abū in the nominative case. At that time, Abū Mūsā had in his service a scribe who had a poor grasp of correct usage. This scribe did not place the letter yā’ to indicate the genitive in place of the wāw, which is a sign of the nominative for the Five Nouns (al-asmā’ al-khamsah). When ¢Umar was shown the book, the solecism stood out to him. Perhaps out of anger at what would happen to the language if such misuse continued and spread, in his reply, he ordered Abū Mūsā “to discipline the scribe and then remove him from his post.”

That this man should lose his employment and suffer the chastisement seems a harsh punishment, yet it comes from a leader whose justice permeated the world and whose virtue eclipsed that of other rulers. What angered him so such that he felt compelled to administer corporal punishment? Was the sanctity of the sacred law violated? Or was there an innovation in the religion? These considerations were undoubtedly present in ¢Umar’s mind, for the relationship between the sacred law and language is unquestionable, and innovations inevitably occur if tongues and pens alike err.

We also see that the first caliph, Abū Bakr al-Śiddīq, lamented the solecisms of people and their imprecise diction. It is recorded in the Rabī¢ al-abrār of Abū al-Qāsim al-Zamakhsharī (d. 538 AH/1144 CE) that Abū Bakr al-Śiddīq, God be pleased with him, passed by a man called Abū Lafāqah, who had a garment in his hand. Abū Bakr said to him, “Are you selling this garment?” Abū Lafāqah replied, “No God’s mercy be upon you.” Abū Bakr then responded to him, “When you are upright, your language usage, too, will be upright. Do not say that, but say, ‘No, and God’s mercy be upon you.’” This is because to simply pause and not add “and” could be misconstrued as a prayer against him, as in “May no mercy of God be upon you,” rather than what the reply intended for him. Comportment and decorum in language demand inserting “and” between the negation and the prayer, because the negation is declarative, while the prayer—although meant in the optative mood—is phrased as a predicate, and so adding “and” provides a coordinating conjunction, which acts as a comma and removes the ambiguity.2

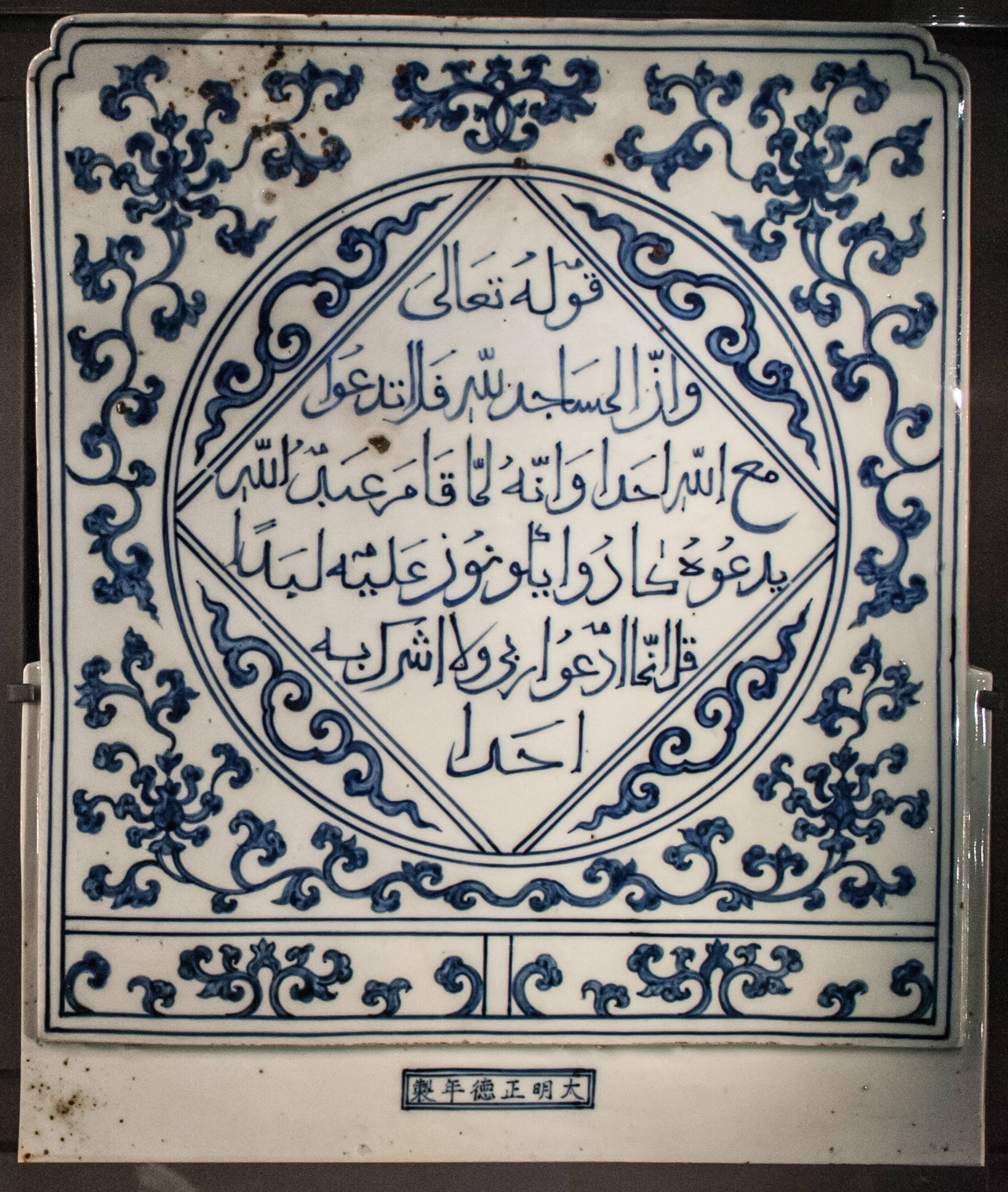

Tablet with Arabic calligraphy, Ming Dynasty, ca. 1500

We can see from this that the preservation of language concerned Muslim leaders greatly. Their concern was such that our tradition holds that the Caliph ¢Alī taught Abū Aswad al-Du’alī to categorize Arabic into nouns, verbs, and prepositions and particles, and then said, “Proceed in this manner” (unĥu hādhā al-naĥw). Some say the term for Arabic grammar, naĥw, resulted from this incident. Others, such as Abū Manśūr al-Azharī (d. 370 AH), claimed it originated from the Greek Ioannes, which is where the name John of Alexandria comes from. Ibn Sīdah (d. 458/1066) said that naĥw was derived from the word intaĥāhu, meaning “he sought it out,” because he sought out the manner in which Arabs spoke, the workings of the language, its declension, use of the dual and plural, and how to formulate diminutives and broken plurals. Many Arabic grammarians favor Ibn Sīdah’s position.

The books of jurisprudence and sacred law record incidents between jurists and grammarians, often in the presence of caliphs, that are just as intriguing. One such incident occurred between the grammarian and Qur’an transmitter Abū al-Ĥasan al-Kisā’ī (d. 189/805) and the jurist and qadi Abū Yūsuf, the student of Abū Ĥanīfah. Al-Kisā’ī challenged Abū Yūsuf, saying, “Are you up for a question?”

Abū Yūsuf inquired as to the nature of this question, “In grammar or law?”

“Law,” replied al-Kisā’ī. At this, the caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd laughed so hard he stomped his foot, as the narrator of this story relates, in shock at this proceeding. But al-Kisā’ī continued, addressing Abū Yūsuf, “What say you about a man who said to his wife, ‘You are divorced when entering the house’ (‘Anti ţāliq an dakhalti al-dār’), and he placed the diacritical mark of fatĥah on the hamzah?”

Abū Yūsuf said, “She will be divorced if she enters the house.”

Once it had become clear to him that he had hit his mark, al-Kisā’ī said, “Incorrect. The woman is already divorced. This is because the husband did not make the divorce conditional; he predicated it with the preposition an with a fatĥah, making it a gerund. It is as if he said, ‘You are divorced because of your entering the house.’”

At this, Abū Yūsuf was quite impressed, and from then on, he was known to frequent the house of al-Kisā’ī. On this, al-Shāţibī comments, “This issue, while a linguistic one, is foundational to both fields of study: law and grammar.”

In a similar spirit, Caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd asked Abū Yūsuf the reason for using the nominative and accusative cases in the words resolve and thrice, respectively, in the following lines of poetry:

If you be gentle, O Hind, gentleness is more righteous,

If you be cruel, O Hind, cruelty is more sinister.

So you are divorced, and divorce needs resolve,

Thrice, and whoever is cruel is rebellious and oppressive.

Whether the words thrice and resolve are in the accusative or the nominative can give the exact opposite meaning. When Abū Yūsuf read the letter, he said, “This question concerns both grammar and jurisprudence. I do not feel safe from error if I speak based on my opinion alone.”

So, he went to al-Kisā’ī, who was lying in his bed and who then answered, “If thrice is in the accusative case, she is thrice divorced, but if in the nominative, then only once.” The ambiguity results from the different uses; in the accusative case, thrice would indicate specification for the ambiguous term divorced in the phrase “you are divorced (i.e., three times).” However, if thrice is in the nominative, while resolve, too, is in the nominative, then thrice becomes part of a predicate for divorce, which would then become the subject of a new sentence.3

Then, Abū Yūsuf sent a message to the caliph, who was so impressed that he sent him a gift. Abū Yūsuf in turn sent this gift to al-Kisā’ī. There are other linguistic dimensions to these verses of poetry that are further discussed in ¢Abd Allāh b. Hishām al-Anśārī’s (d. 761/1359) encyclopedic work Mughnī al-labīb.

Arabic language and grammar were deemed so essential to hermeneutics that some grammarians eventually began to issue fatwas. Abū ¢Umar al-Jarmī said that he used to issue fatwas on the basis of Sībawayh’s book for a number of years. And it is well known that this book was a book on grammar and not law. Some interpreted his statement to mean that he knew the hadiths well and simply used Sībawayh’s book to bring out the sundry and subtle meanings of the language, as well as the conventions of the Arabs.

Editor’s Note: This excerpt, translated by Hamza Yusuf and Asad Tarsin, is taken from “The Necessity for a Jurist to Master the Arabic Language,” a paper by Shaykh Abdallah Bin Bayyah written specifically for jurists, scholars of Islamic law, and students to underscore the primacy of studying Arabic in the Islamic legal tradition. In this short section, Shaykh Bin Bayyah illustrates the extraordinary relationship the early generations of Muslims, beginning with the Prophet Muĥammad’s Companions, had with the Arabic language.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy