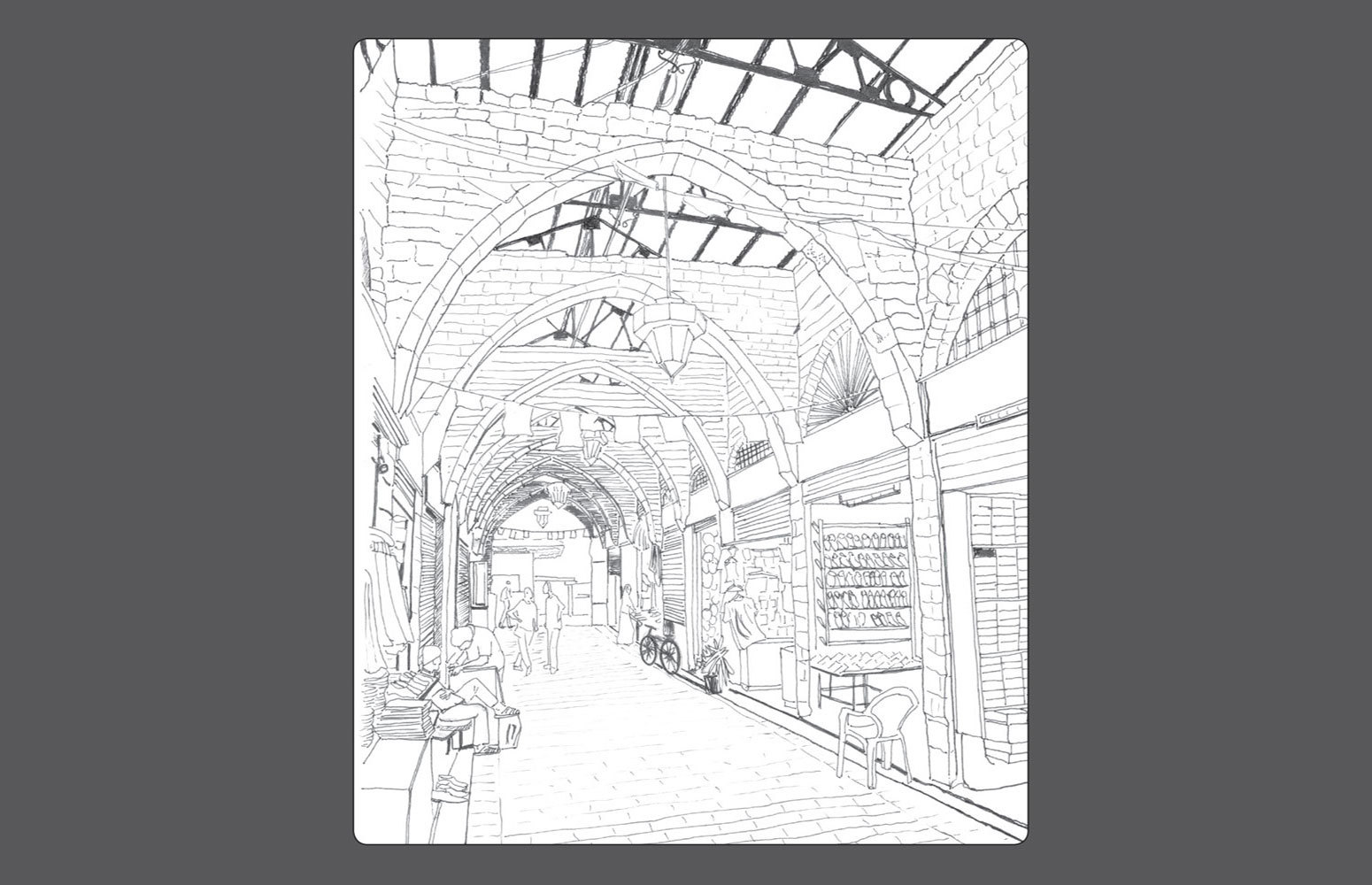

The interior of the arcaded section of the Old Souk in Homs, illustration by Marwa al-Sabouni; all of the illustrations in this essay were first published in The Battle for Home by Thames and Hudson.

The assassination of Muhammad Said al-Bouti, one of contemporary Islam’s most distinguished scholars and impressive minds, represents one of the great losses of the devastating Syrian civil war, a loss that remains all but unnoticed in much of the West.

A suicide bomber murdered Dr. al-Bouti and many others in a mosque located in one of the supposedly safest neighborhoods of the Syrian capital of Damascus, while the scholar, as was his custom for more than forty years, gave a morning lesson on March 21, 2013, to an educated and faithful audience; many of these devoted students also died in the bombing.

The crime remains officially unsolved to this day: Syria’s warring factions blamed each other as they washed their hands of the blood that stained the carpets and walls of the Iman Mosque and dripped on the pages of the Qur’an that Dr. al-Bouti held as he discussed the verses of Surah al-Imran that fateful morning. As a scholar, he was prolific, leaving behind a legacy of more than sixty books and countless recordings in which he addressed innumerable controversies and challenges related to Islam, Muslims, and our recent times.

One book in particular, Dialogue About Civilizational Issues, wrestles with one of today’s most pressing questions: Can Western culture and Islamic culture be reconciled? The struggle for identity, which dominates virtually every aspect of life in a troubled region the world has called the Middle East, lies at the root of this question.

As a Syrian architect, I have been occupied with this struggle ever since I was a student trying to understand a parallel problem all architects, even those in the West, grapple with in this new era: In which style should we build? The question remains unanswered after modernist architecture and globalization appropriated any attempts to define an authentic architectural style; the Middle East, meanwhile, remains a region where even the application of modernism has failed.

The clash between the old Islamic city and the architecture of colonization remains evident all over the Middle East. In Syria, during the early twentieth century, French colonial authorities, using urbanization principles alien to the Syrian context, re-planned the old Islamic cities to enforce control and compartmentalize society. In the 1930s, the French assigned architect Michel Ecochard the task of “modernizing” the Syrian Islamic “vulgar” city as part of their urban colonial strategy.

As in post-revolution Paris, colonial urbanization introduced the Haussmann principles of wide-open streets and boulevard planning and pushed the city’s growth outside the old city’s walls. Newly created modern boulevard housing created class division by luring the wealthy away from the old city and also encouraged sectarian division, as economic and political favoritism pitted one sect over the other, consequently isolating neighborhoods.

Colonial urbanization proved neither subtle nor nuanced, it required blowing up entire Damascus neighborhoods, making clear-outs in various parts of the city, and relocating entire monuments to thin the traditionally uncontrolled, closely knit urban fabric. To maintain these wholesale changes, administrators tailored building and planning laws and legislation to better fit the task of modernization as a form of political control and a fulfillment of economic interests.

As a defeated Islamic ummah, the people of the fallen Ottoman Empire have found themselves residents of new territories marked by British and French colonization. The flux of identities—traditional and modern, Islamic and Western—competed in the encounter between the victorious Western and new styles and the defeated old local ones. A rupture still prevails almost a century later, with no apparent ending.

In The Battle for Home, a book I wrote in the midst of one of the most vicious manifestations of this struggle (termed for a short while the “Arab Spring,” and later by locals, more aptly the “Third World War”), I explained how the built environment—the place where we build who we are, who we wish to be, and who we fail to be—plays an essential role in creating conditions for war and for peace. Unlike our history books, our buildings cannot tell us false narratives. They are not only the embodiment of ambitious aspirations and imaginations but also the expressions of skills and power, as well as economic, social, and political victories. To be erected, buildings need more than brick and mortar; they need a hierarchy of crucial decisions, which are always preceded by long and tiring—and in most cases brutal—battles that occur in the social and political arenas of our societies.

These battles tell us what is important to a local community, or even if this community exists in the first place: Does it have a voice? Is it armed with proper awareness? Does it possess the requisite level of democracy or political freedoms? Does it enjoy wealth? Is it ruled by capital? Is it subject to divisions and sectarianism? Is corruption the official means of administration, or does bureaucracy rule? These dynamics and many others transfer buildings from imagination into reality, and by that, they endow the buildings with the rare quality of becoming the most trusted and most authentic means of media, of communicating the society’s values. There is no room for fake news in this process; the outcome—the buildings—speaks truth and nothing but truth.

When Dr. al-Bouti opened his book with his question about the viability of reconciling dramatically different cultures, he almost answered it before writing the rest of his chapters simply by rhetorically inquiring whether Islam represents the rooted origin and Islamic civilization its branch or whether Arab civilization represents the rooted origin and Islam its branch. According to him, the first understanding relates Islamic civilization to Islam in the natural order by which any origin relates to its branch, similar to tracking the descent of a child to his father. Whereas embracing the latter understanding means reversing the order, as if the father descends from his child! Regrettably, we in this region have chosen to follow the latter, for reasons far too many to recount here, but a look at the destruction and devastation in the fatherless society we have adopted points to the perils of such an illogical approach.

In Syria, we chose to build according to what was sold to us as “modern and progressive,” for which we traded our close-knit neighborhoods, our modest and inward houses, our unostentatious mosques and their neighboring churches, our collaborative and shared spaces, and our shaded courtyards and knowledge-cultivating corners, leaving us with isolated ghettos and faceless boxes. We replaced our local trades, crafts, and economies with foreign companies and banks; our productive lands with vacant blocks; and our harmonious communities with segregated and antagonistic ethnic and religious groupings.

Some Syrians identified the problem as losing our identity and fought the imported (and enforced) alternative, but reflexively they believed the solution to be to simply go back in time to an imagined point when we were creators, before we began to consume. Inspired by the impressive structures and buildings that remain part of our heritage, they embarked on a project of mimicking the creations of our ancestors. So a movement of attached domes, star-based geometries, and random arches began to flourish, sometimes even within imported Western styles adopted locally. This trend become pervasive all over the Middle East; our cities boasted towers with hat-like domes on top, glass facades with composite arches on their surfaces, and boxy mosques with multiple tapering minarets piercing the skies. Predictably, these efforts failed our identity further because they were rooted in mere mimicry, not the essence of what made the Islamic city and Islamic architecture “Islamic” in the first place. The builders of those old structures were not searching for identity; their identity was firmly rooted within them—they only had to express it. The successful lessons found in the old cities should not be learned nostalgically, through a mere copy-and-paste approach that many projects making reference to the region’s cultural heritage fall into. Designing and building are a production process, which like every creative act of producing, demands a core of meaning that looks for ways to be outwardly expressed.

The admired places in the old Islamic city contain much more than an outer form. Their builders considered and interwove multiple functions; in these cities, different backgrounds and social classes intermingled in environments that had a well-considered sense of scale, proportion, and detail and that were built with sustainable and resilient materials, achieving high standards of what we call today passive design techniques, or green design. But, for these medieval builders and city planners, it was simply good architecture, springing from their philosophy about themselves and the universe.

Moreover, the Islamic old cities had the unique quality of a layering approach—namely, the use of other civilizations’ elements, structures, and techniques to produce a new outcome. This philosophy of encompassment mirrored the encompassment of the religion. For instance, most of what remains in the old cities in Syria belongs to the Ottoman era, some to the Mamluk, and some to the Ayyubid Islamic styles; amazingly, you also will find elements belonging to the Hellenistic or Roman eras incorporated within these structures. These buildings were embodiments of what the term urban fabric means: acts of interweaving society as well as stone.

This sense of incorporation and harmonic blending extended to the details of life in those urban settlements, whose residents picked up on these characteristics in their own relationships. Architecture defined a city as a place for people, nature, and economic activity to thrive, not as a place littered with box-like buildings capable only of encapsulation, nor as kitsch.

The main drawback of promised progress, which has turned out to be a fertile ground for conflicts, is its failure to cultivate our inner expressions; through its foreign nature, it alienated our communities from themselves and shredded their lived realities.

At such a time, Dr. al-Bouti’s question becomes more relevant than ever. There is no third option: either we construct the Islamic identity to fit the fixed and rigid mold the modern West offers or we revisit this abandoned and wounded culture and embrace it back to health again. Nonetheless, we often hear arguments that the Western mold, in fact, proposes to “repair” Islamic culture. This, however, is a very risky fault-line because the Western idea of “repair” simply points to the Christian Reformation in the fifteenth century. The mold is carved according to Western measures, to what the West knows and to what it has experienced, not to what the people whose communities need “repairing” know or have experienced.

We in the Middle East must be wary of the colonial inheritance of the West, with which comes our status as an inferior partner (if not a subject). Losing our identity in exchange for the Western idea of “progress” has proved to have greater consequences than we could predict. This vacuum in our identity could not be filled by imported “middle grounds,” as was once naively thought; this vacuum was instead filled by horrors and radicalizations, by sectarianisms and corruption, by crime and devastation—in one word, by war.

If, as Muslims, we are serious about an awakening, and if the West is serious about a reconciliation, we must be sincere in our own intentions toward our own identity. We must realize the desire to regain it in order to regain peace. And in order to do so, we simply have to do exactly what any dedicated farmer does to a plant: cultivate the roots and carefully prune the branches.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy