Companion Article

The author explains how she identified enslaved Muslim women for this article.

Read Time

|

Sylviane A. Diouf

Brown University

Sylviane A. Diouf is a social historian whose research interests include the trans-Atlantic and trans-Indian Ocean slave trades, West African Muslims, and resistance to slavery.

More About this Author

Companion Article

The author explains how she identified enslaved Muslim women for this article.

The Untold Stories of Enslaved African Muslim Women in the Americas

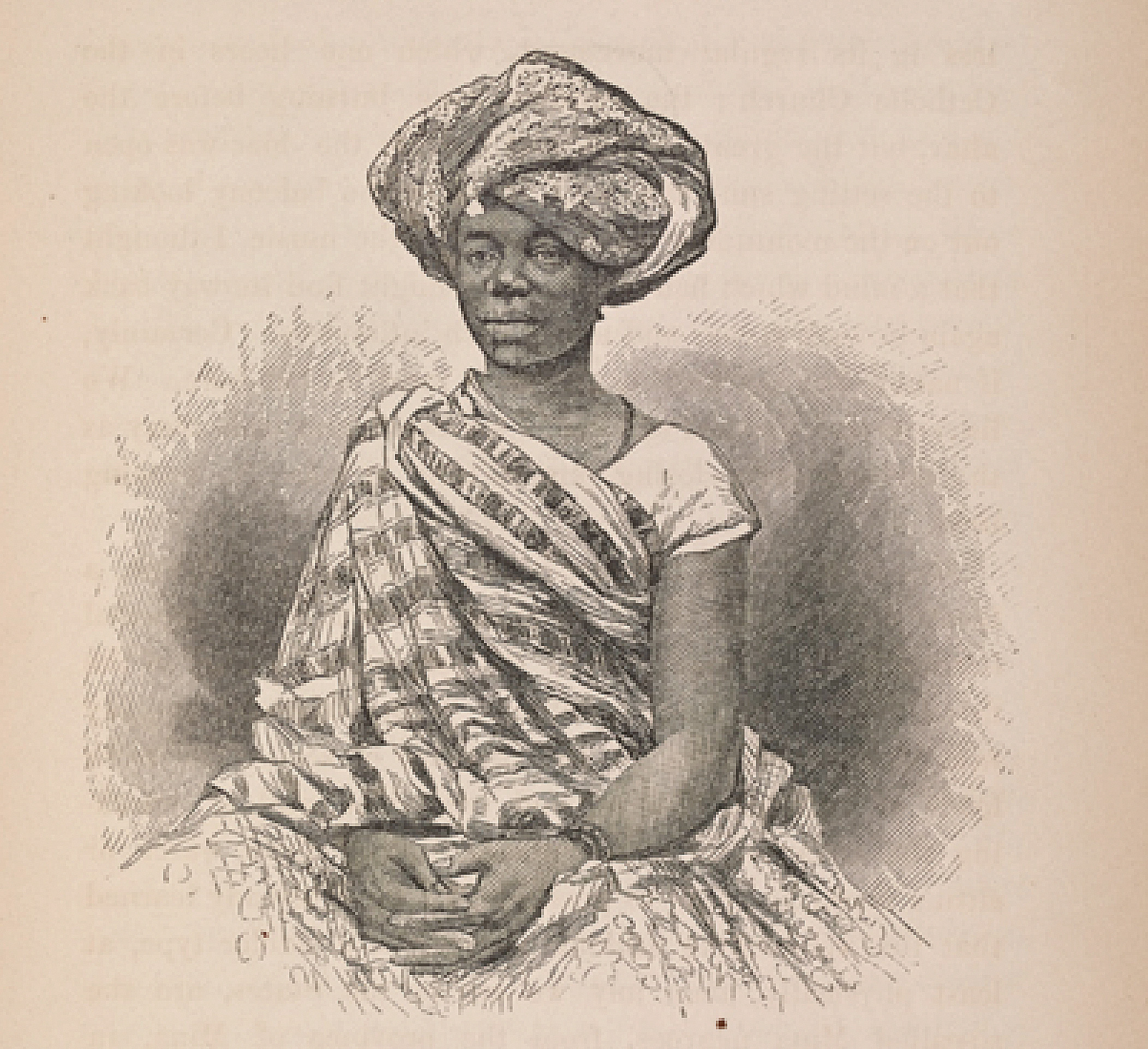

An enslaved Muslim in Rio, wearing the typical shawl and headdress of Brazilian Muslims; General Research Division, The New York Public Library, 1868

Among the enslaved population of Africans in the Americas, Muslims were a minority, and yet their contemporaries—slaveholders, scholars, diplomats, writers, priests, political figures, and missionaries—wrote a great deal about them. Moreover, portraits, photographs, testimonies, artifacts, documents, and, crucially, manuscripts written by the Muslims themselves give us a unique insight into the history and stories of African Muslims.

But while men received an exceptional amount of attention, Muslim women, like other enslaved women, have been the forgotten ones.

Yet we can shed light through anecdotes and stories gained from records, which reveal the plight of Muslim women from ethnic groups in West Africa such as Mandinka, Wolof, Hausa, Yoruba, and Fulbe—their attempts to escape, their chanting of du¢ā’ (supplications) to God, their making of rice cakes offered as śadaqah (charity), the branding of slaveholder names on their bodies, and their resilience during enslavement.

In Search of Freedom

Whether deported from Africa or born in the Americas, Muslim women tried, when they could, to recover their freedom by running away. South Carolina–born Fatima ran away in July 1786, along with “Sambo” (or rather Samba—which means “second son” among the Fulbe) from the “Guinea country.”1 Another Fatima, twenty years old, was advertised as a runaway in the same state on July 19, 1808. She spoke very little English and may thus have arrived after the slave trade had been abolished on January 1.2 In Louisiana, three recently arrived Mandinka—two females aged fifteen and nineteen, and a young man—looked for freedom in November 1806.3 A thirteen-year-old girl

and five males, all Mandinka, were advertised as runaways on July 12, 1785. They had arrived from Gambia just six

weeks earlier.4

Runaway notices from Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti) show the appalling brutality of slave owners, who branded their full name and hometown on people’s bodies. One slave owner was looking for a Mandinka “branded on one breast DVMON, below P. AV PRINCE, the brand is a little burnt and on the other breast D.”5 The Mandinka Jeanne had marks of whippings on her face.6 Motherhood, shackles, and mutilations did not deter some Wolof and Fulbe women from looking for freedom. Victoire escaped in July 1766 with her fifteen-month-old son. A year later she ran away again, with a leg shackle, and was still at large two years later.7 Martonne ran away with an iron collar with three high branches around her neck and managed to stay away for at least eighteen months.8 Flore and Silvie had part of an ear cut off, a standard penalty for recidivists.9

Running away sometimes meant becoming a maroon, a person who had left the slave world behind to settle in the

forests. In the United States, the most

fascinating maroon community developed in the 1780s in Georgia. Its size, the large settlements it established—one of which was cleverly fortified—and the resistance the maroons put up when attacked make it a distinctive case in United States history.10 Among the maroons was Fatima, one of at least nineteen identifiable Muslims enslaved by Georgia Lieutenant Governor John Graham.

The community Fatima joined—along with Muslims Mahomet and Demba—numbered over a hundred people. Other Africans were probably part of the group: 75 percent of runaways in colonial Georgia and 68 percent in South Carolina were born in Africa.11 There were undoubtedly Muslims among them. Between 1760 and 1774, over 18,000 people from Gambia and 3,300 from Saint-Louis in Senegal arrived in Savannah and Charleston. They came from areas that had not only significant Muslim populations but also high numbers of Muslim victims of the slave trade, which led to the 1774 jihad in Futa Toro (Senegal), whose stated objective was to stop the deportation of Muslims.

The American maroons had houses, fields of rice and corn, and canoes. After they were attacked three times and fought back twice, they disappeared. It took the militia two days to burn down their houses and fields. The maroons moved to a fortified camp with sentinels and breastwork to protect their twenty-one houses and their fields. Georgia and South Carolina united to annihilate them. An attack in May 1787 killed six maroons, while others fled. Mahomet, who years before had one ear cut off as a habitual runaway, was among the dead. Fatima, another four women, and a child were apprehended as they tried to get to Spanish Florida.12 The sheriff placed a newspaper ad asking their enslavers to pay for their upkeep and take them away as he did not want to be held responsible in case they escaped.13 Fatima’s fate remains unknown. As was always the case with maroons, she certainly endured gruesome torture—sometimes followed by death—as a deterrent to others.

Revolt in the Pacific Ocean

A bloody and mutinous incident took place in the dark of the night on a ship sailing from Chile to Peru, and it sheds light on the role of Muslim women in supporting the men in the uprising. The episode, which inspired Herman Melville’s celebrated novel Benito Cereno, began on December 20, 1804, when twenty-eight females, nine “suckling” infants, three local black men, twenty teenagers, and twelve (or thirteen) adult men embarked from Valparaiso, Chile, on the Tryal.14 According to the captain, Benito Cerreño, the adult men were all from Senegal.

Six men’s Senegalese origin and Islamic religion can be clearly established, but another six names originated in Nigeria.15 The women’s names were not recorded.

The group’s ordeal had started weeks earlier when they were marched from Buenos Aires, Argentina, to Valparaiso, a harrowing walk of one thousand miles, including four hundred up and down the steep Andes. They were the property of the Argentine slave owner Don Alexandro Aranda. He too was on the ship. He planned to sell the Africans in Peru. Everything went smoothly until the night of December 26. For the Christians on board, that night had no special meaning, but for the Muslims it was the most important night of the year, Laylat al-Qadr, the night of Destiny or Power. In the morning, a revolt erupted. Its leaders were Babo, fifty years old, and his son Mori. The teenagers were not involved in the uprising; only the men and the women were. Cerreño testified that just before the revolt started at 3:00 a.m., the “negresses of age were knowing to [sic] the revolt, and… began to sing, and were singing a very melancholy song during the action, to excite the courage of the negroes.” Laylat al-Qadr being a night when supplications are granted, what they probably were chanting were supplications, du¢ā’, an act of worship to ask God for forgiveness and favors, to

solicit His help to change one’s destiny.

As the women chanted, the revolt began, and eighteen sailors were killed. Mori asked Cerreño if there were “negro countries” around where they might be taken to. Told there were none, the young man ordered him to sail to Senegal. Then Babo and Atufal forced Cerreño to write and sign a document stating he would take the ship to Senegal. Both men signed it in Arabic. Before they had been deported, a momentous event had taken place in Ndar, the city the French named Saint-Louis du Sénégal, and the Senegalese on board the Tryal were obviously aware of this amazing odyssey. In 1800, sixty-five to seventy Senegalese en route from Montevideo to Lima had overtaken the ninety-man crew of the San Juan Nepomuceno. Five months later the survivors—twenty-four people had died—made it to Ndar. The only successful ship revolt was also famous in South America. It inspired the viceroy of Peru to urge the Spanish Crown to, once again, prohibit the introduction of Muslims because they “spread very perverse ideas” among other Africans, of whom there were “so many… in this realm.”16

Three weeks after taking over the Tryal, the Africans killed another seven men, including their slave owner, Don Alexandro Aranda. At that moment, Cerreño recounted, the women again “influenced the death of their master” by singing their “very melancholy song.” He added that “they also used their influence to kill the deponent.” For almost two months the Tryal sailed up and down the Chilean coast. One woman, one infant, and two teenagers died of hunger or thirst. The ship was eventually approached by Captain Amasa Delano’s whaler, and a remarkable deception took place. When Delano boarded the Tryal, the Africans posed as docile slaves under Cerreño’s command. Always flanked by Mori and Babo, Cerreño played along until he could escape to Delano’s ship and reveal the revolt. Delano sent twenty men to the Tryal. During a four-hour fight, the Africans showed “desperate courage.” Babo and another six men were killed, and Delano discovered “a truly horrid” carnage. Some men were eviscerated; others had the skin of their thighs and backs shaved off. Three days later, the Tryal arrived in Chile. Mori and seven men were tried, then dragged “from the prison, at the tail of a beast of burden,” and hung. Their heads were cut off and placed on pikes, and their bodies were burned. The women, the teens, and the surviving men were brought to the square to watch the gruesome execution, then they were sold.

Cerreño’s repeated statement that the women influenced the fight is remarkable. Though he did not know the meaning of their “singing,” he understood its significance in the unfolding of the revolt. Although the women did not fight, Cerreño realized that they were a crucial part of the event.

Interestingly, several Westerners noted that Africans sang on slave ships and described the songs as lamentations expressing fear as well as heartache at being taken away from relatives and friends.17 What they probably heard on the ships, including during revolts, were Muslims’ supplications to God. It is significant that Senegambians, who represented 6 percent of the total number of deportees to the Americas, launched 22.6 percent of the revolts.18 The fact that Islam does not authorize the enslavement of Muslims was likely a contributing factor, as was the prospect of being enslaved by Christians.

Charitable Women

One of the fundamental duties in Islam is to offer charity without expecting anything in return. Whereas zakat is mandatory under strict conditions, śadaqah or freewill offerings are not, but they are strongly recommended.

In the 1930s, Katie Brown, born enslaved on Sapelo Island in Georgia, explained that her grandmother Margaret, a daughter of Bilali Mohamed—a Guinean who wrote a thirteen-page document in Arabic—used to make rice cakes called saraka. Also in the 1930s, formerly enslaved Shadrach Hall mentioned that his grandmother Hester—another daughter of Bilali—made the saraka every month. On St. Simons Island, Ben Sullivan recalled that his father, Bilali—a son of Salih Bilali from Mali—made the saraka. According to Shadwick Rudolph of St. Marys Island, his grandmother Sally’s saraka were the best.19

For the longest time, saraka was thought to mean “rice cakes” in an African language. But, as I show in Servants of Allah, rice balls are West African Muslim women’s emblematic freewill offerings known, depending on people’s languages, as śadaqah, sarakh, sarakha, saraka, and saraa. They are an integral part of religious holidays; Katie Brown mentioned that her grandmother gave saraka once a year, on “a big day.” Rice balls are also offered on Fridays, and they are not called saraka, but giving them is a śadaqah. The alms are accompanied by a supplication to God, and as the women hand out the cakes, they say it is a saraka made in the name of God and say āmīn. Katie Brown remembered the children stood around a table as her grandmother said, “Āmīn, āmīn, āmīn,” before they ate the cakes.

Tradition states that the best śadaqah is given by those who own little. Enslaved women undoubtedly qualified. Their children and grandchildren appreciated their śadaqah so much they created a song:

Rice cake, rice cake

Sweet me so

Rice cake sweet me to my heart.20

Just as with the elderly men and women who described the rice cakes in the 1930s, there is no indication that those who sang (and, decades later, recalled the song) connected it to Islam. If they did, they did not mention it.

In Brazil, Muslim women continued the tradition until at least the early 1900s. In Bahia they prepared balls of sweet rice for religious holy days such as Eid al-Ađĥā (Feast of Sacrifice).21 Śadaqah was also offered in Trinidad until the early twentieth century. African Muslims’ descendants recalled collective saraka gatherings led by religious leaders who said the opening prayers in Arabic. On that occasion, women wore “colorful headties and blouses and skirts.”22

From Slavery to Freedom in the United States

In September 1860, a South Carolina newspaper announced the death of Old Lizzy Gray, “imported from Africa during the Revolution.” She was “educated in her youth under the influences of Mahommedan tenets” but had become a Methodist, and, according to the man who enslaved her, she said that Christ had built the first church in Mecca and his grave was there.23 In all likelihood she said Medina, which, unlike Mecca, was certainly unknown to her interlocutor. But what did she mean? She may have drawn a parallel between Muhammad and Jesus that went misunderstood. Or she might have used a subterfuge to camouflage her faith. Taqiyyah or concealing one’s belief in the face of danger was not unusual. In 1842, Georgia slaveholder and Presbyterian minister Charles C. Jones noted, “The Mohammedan Africans remaining of the old stock of importations, although accustomed to hear the Gospel preached, have been known to accommodate Christianity to Mohammedanism. ‘God’ say they, ‘is Allah, and Jesus Christ is Mohammed—the religion is the same, but different countries have different names.’”24

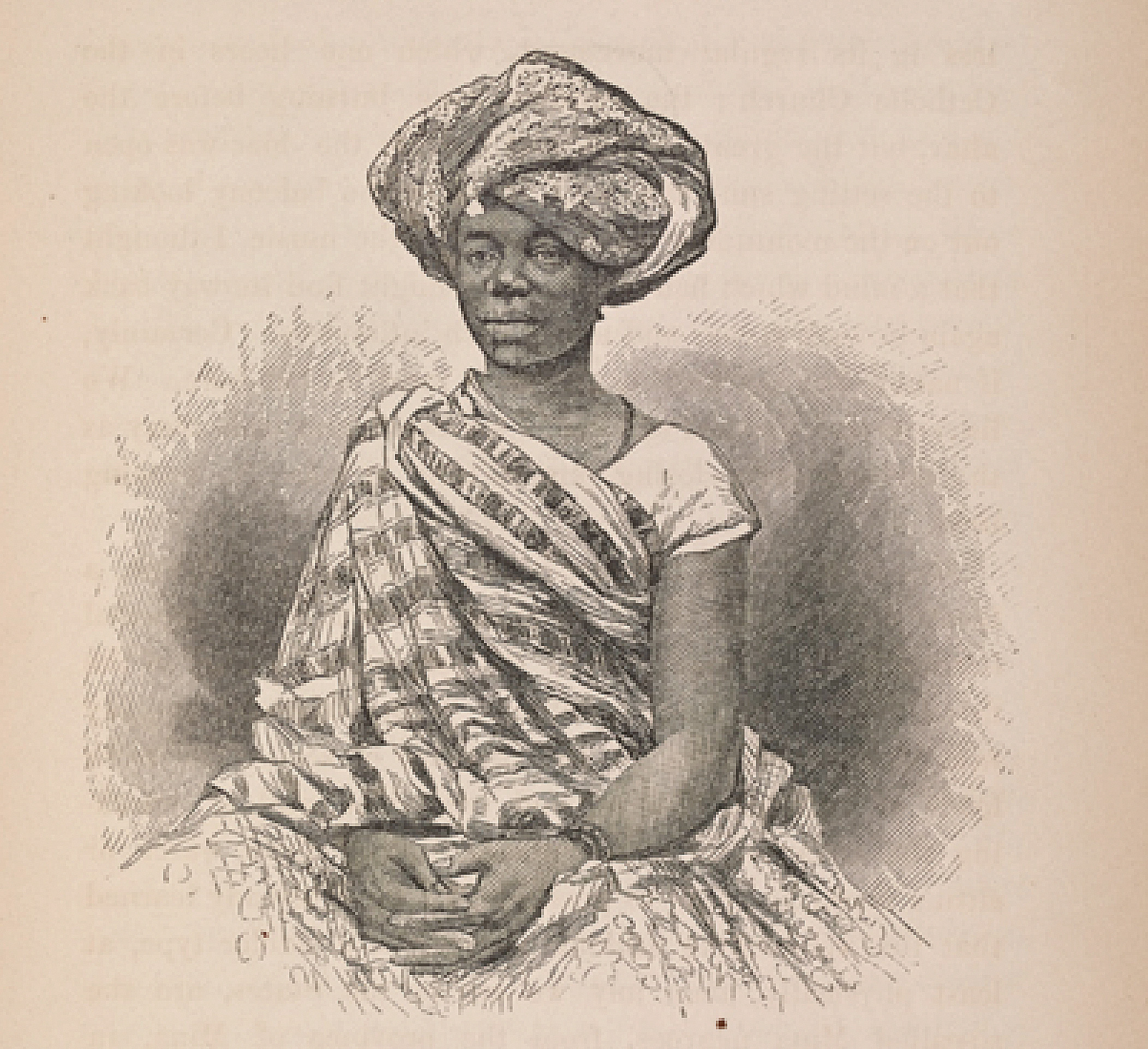

Arzuma, 1912; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Arzuma, a Nupe Muslim from Benin or Nigeria, arrived in Alabama in 1860 on the last known slave ship. She died in the 1910s.

A few African-born Muslims lived into the 1870s and 1880s. On Sapelo Island, Hannah and Calina Underwood, both ninety-five years old, were alive until at least 1870.25 Nero Jones, interviewed in the 1930s, remembered they talked a “funny” language, were very old and very particular about praying. They used a tasbīĥ and, as Calina said “Ameela” (āmīn), Hannah said “Hakabara” (God is great).26 Fatima Williams, born around 1782, passed away in Marion, Texas, in February 1880.27 “Fadooma” Udoo, born in 1800, lived in Matagorda, Texas, until at least 1880. Fifteen black Fatimas—four were born in Africa—were enumerated in South Carolina in 1870 and 1880.

In July 1860, Arzuma (Friday), a Nupe Muslim from Benin or Nigeria, landed in Mobile, Alabama, after a six-week journey on the Clotilda, the last slave ship to the United States. Enslaved, like her 107 companions, she was freed five years later. In the early 1870s, those who lived in Mobile founded their own neighborhood called African Town. Arzuma died in the mid- to late-1910s, arguably the last formerly enslaved African-born Muslim woman in the United States.28

Into the Twentieth Century in Brazil

In 1890s Bahia, the imam was a Yoruba. His Creole wife had lived in Rio, where she converted to Islam, an indication that some proselytizing was still going on. She was “very versed in reading the Qur’an.” Since she didn’t know Arabic, her Qur’an was in Portuguese.29

At the turn of the twentieth century, Muslims attracted the attention of writers and academics. In the 1910s, Afro-Brazilian ethnographer Manuel Raimundo Querino described how they observed Ramadan in Bahia. The dishes the women prepared showed the diversity of the community. The morning dish of boiled yam, mixed with efo, was a typical Yoruba dish. The fura or afura, ground millet molded into balls and mixed with fermented milk, was a Fulbe and Hausa specialty. On Eid al-Ađĥā they danced, carrying a cloth around their necks. When one finished the dance, she passed it to another.30

Querino remarked that marriage was “observed with rigor, in the same way as a fraternal friendship,” and polygamy was practiced as “an hygienical measure.” Fathers often married their daughters to their friends. Wives who did not fulfill their conjugal duties were abandoned by the community, but no one, including their husband, could touch them. An unfaithful wife was allowed to leave the house only at night and always accompanied by someone the husband trusted. Querino’s description of a wedding is worth reproducing in full:

When they wanted to marry, the bride, the groom, the godparents, and the guests went to the imam’s house. He would ask the couple to think carefully about the action they were about to take in order not to regret it later. He gave them a few minutes to reflect and then asked if they were sincerely getting into the marriage on their own freewill. If so, the bride, dressed in white with her face covered with a light veil, placed a silver ring on the finger of her future husband. The groom dressed in wide “Turkish” style trousers would give a silver chain to his wife. They repeated the words “sadaka do Alamabi” [Hausa, sadaka don Annabi: “a gift for the Prophet’s sake”]. They would then kneel, and the imam started the ceremony telling them about each one’s duties and exhorting them to behave well and not to deviate from their obligations. In the end, the young couple stood up and kissed the imam’s hand. After the ceremony people went to the house where a banquet was held. Everyone sat down while the bride walked to the center of the room, clapped her hands, “recited a song” and returned to her seat. The food consisted of chickens, fish, and fruit.31

While they maintained religious and cultural traditions, Brazilian Muslim women introduced new concepts. In 1865, traveler ¢Abd al-Raĥmān al-Baghdādī was incensed at the fact that Muslim women in Rio inherited half of their husband’s assets while the other half was divided equally among their sons and daughters, contrary to the shariah. Despite his admonitions, the women did not budge.32 Clearly, the men agreed with this innovation.

According to a disapproving al-Baghdādī, women “went to the markets without covering themselves.” Unbeknownst to him, women in West Africa did not routinely wear veils; he also failed to see that in Brazil they had their own dress code that distinguished them from non-Muslims. In Rio, they wore high muslin turbans and long, bright-colored shawls, “either crossed on the breast and thrown carelessly over the shoulder, or if the day be chilly, drawn closely around them, their arms hidden in its folds.”33 In the 1930s, Gilberto Freyre noted, “In Bahia, in Rio, in Recife, in Minas, African garb, showing the Mohammedan influence, was for a long time worn by the blacks.”34 With the blue pigment imported from West Africa to make the ink used to write

on alwāĥ, women underlined their lower eyelids.35

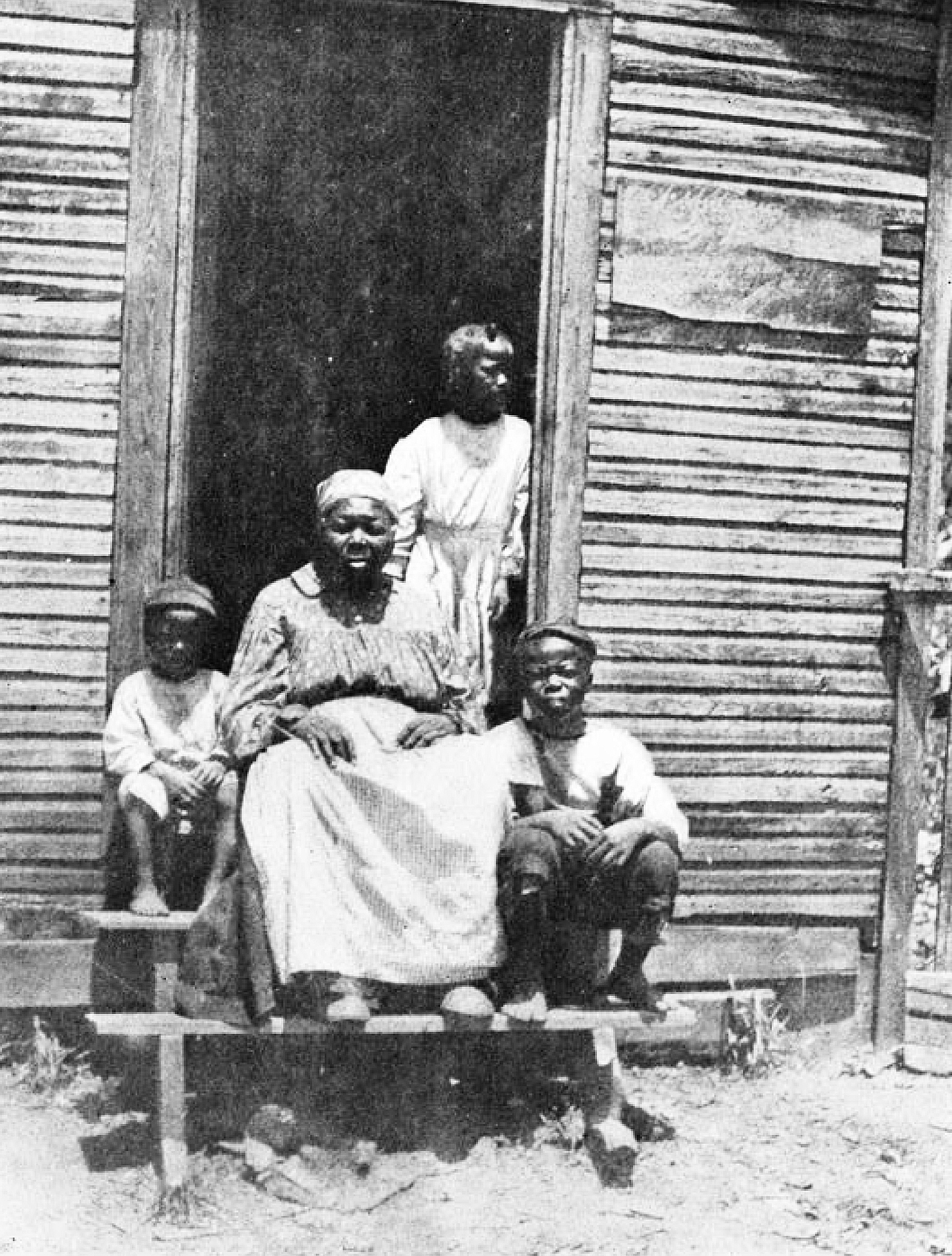

Tia (aunt) Ciata; Casa da Tia Ciata Institute. The most celebrated émigré from Bahia, whose real name was Aissata (Aisha), was a renowned cook and entrepreneur in Rio. She died in 1924.

Passing on Islam

As noted earlier, African religions and cultures were most often passed on from mothers to children. But inevitably, the transmission did not always work, as Munsilna McGundo’s story shows. She arrived in Charleston in April 1806, one of 230 East Africans brought by Zephaniah Kingsley, who retained eighteen for his Florida plantations.36 Munsilna, whom he raped on the ship, was pregnant. She has been portrayed as of “unknown ethnicity.”37 Yet obvious clues point not only to her real name but also to her ethnicity and religion. The Ngindo—also known as Magundo and M’gindo—live in southeastern Tanzania. Munsilna is the Arabic Muhsina. In February 1807, Muhsina, who through her names had successfully claimed her religious and ethnic identity, gave birth to a daughter. She named her Fatima.

Shortly later, Kingsley bought and raped thirteen-year-old Anta Madjiguène Ndiaye, a Senegalese Muslim said to be a daughter of the king of Jolof. The teenager’s son was named George, and Ndiaye converted to Catholicism a few years later. There is no recorded conversion for Muhsina, but Fatima baptized her daughter, Mary Martha, in the Catholic faith. Muhsina’s observance of her religion, and her privileged position as one of Kingsley’s four freed African co-wives, had little effect on her descendants. She might have instructed Fatima in her religion, but her daughter did not follow in her path.

Four women and five men interviewed in the late 1930s in six of the Sea Islands of Georgia provided the most detailed information on the dynamics of Muslim families. All but one described their grandmothers—not their parents—praying or giving saraka (śadaqah). It is tempting to conclude that the second generation did not follow Islam. However, the informants were asked a leading question: Had they known Africans? Naturally, they talked about their African-born grandparents. The only person who made a reference to a parent was Ben Sullivan, who stated that his father, Bilali, a son of Salih Bilali, made the rice cakes. The fact that Bilali engaged in an exclusively female activity shows that he knew what it meant and how important it was. Had they been asked a neutral question, it is conceivable that other informants could have mentioned their parents’ prayers and charity, if indeed they too were practicing Muslims. Two descendants, without being prompted, volunteered information about their grandmothers’ particular way of praying.

Four of Phoebe and Bilali Mohamed’s seven daughters—Margaret, Hester, Charlotte, and Bintu (listed as Pinta)—lived in the 1870s. One of Bintu’s granddaughters, Harriett Hall, born in 1854, was, according to her own granddaughter, a practicing Muslim. If this is the case, she might have learned about the religion from her own mother and/or from Bintu, who was alive until Harriet was at least sixteen. When she was twelve, Harriet joined the First African Baptist Church. Yet she often went to the woods to pray. According to historian Michael Gomez, this secrecy may indicate that she continued to practice Islam.38 Harriett passed away in 1922, perhaps a fourth-generation Muslim and thus an exception.

Conversions and ambiguity could also be found in Brazil. Carmem Teixeira da Conceição, born in 1877 in Bahia, had moved to Rio, where she lived in the same building as Alufa Assumano (Usman), who baptized her children in the Islamic faith. After she converted to Catholicism, she “blessed herself when she spoke of him” and stressed that the Muslims were “a very respected sect.” In 1983, when manuscripts in Arabic were discovered, Tia (aunt) Carmem was asked to decipher them. She recognized the writings and signs as common in the religious practices of Muslims.39

In Rio, the most celebrated émigré from Bahia was Hilária Batista de Almeida. Known as Tia Ciata, she passed away in 1924. It is now acknowledged that her real name was Aisha. However, Ciata was rather a diminutive of Aissata, a West African variant of Aisha. Tia Ciata had fifteen children; one daughter was named Fatuma, and her eldest daughter’s husband was named Abul.40 Tia Ciata, a renowned cook and entrepreneur, was a mae de santo—the second-highest position in Candomblé, an African syncretic religion that developed in Brazil in the nineteenth-century—and was also instrumental in the development of samba and Carnival.

Carmem and Ciata’s stories are representative of the experience of the Muslims’ progeny. In 1865, al-Baghdādī asserted, “The majority of children turn out to be Christians.”41 In the 1890s, Muslims themselves complained of the “ingratitude” of their children who preferred the “fetishist life” of the followers of the Yoruba religions or Catholicism to the faith of their elders.42 By then some Arabic words and Islamic practices had been incorporated—through outsiders’ observation and likely by Muslim converts and Muslims’ descendants—into Afro-religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda.43 Islam was a minority religion, and it did not accommodate syncretism. In addition, the traditional means of diffusion such as schools, books, communal prayers, celebrations, and assemblies, were out of reach. Despite its followers’ efforts Islam survived in the Americas due to the continuous arrival of Africans, not due to widespread intergenerational diffusion or conversions.

What Sustained the Women

Much about enslaved Muslim women remains to be uncovered. To be sure, their lives were somewhat like the lives of Muslim men, of other African women, and of native-born females as well. However, part of their experience was distinctly theirs. They knew they were not to marry a non-Muslim, but they had no recourse when forced to do so. According to the only law they knew, children followed their father’s status and thus were free at birth and considered legitimate if their father was free. But in the Americas, children followed their enslaved mother’s status. According to the Islamic law of istīlād, a woman who had children by her sexually abusive enslaver could not be sold and was automatically freed after his death. Freeing enslaved people was considered a blessing and part of the duty of charity, as stated in Sura al-Nūr (Qur’an 24:33).

The women’s realization that they would spend the rest of their lives in a society where manumission, or the release from slavery, was rare and that they and their children had no protection must have been devastating. Living that life was, naturally, infinitely worse, especially for those who were isolated and could not count on a community’s support. Yet in these dreadful circumstances Muslim women remained faithful to a religion that sustained them. Those who were able to do so kept and sometimes imposed their Muslim names; dared walk into the unknown to regain their freedom; offered alms; and passed on what religious and cultural knowledge they could to their children. These women’s stories, however rare and incomplete they are, are distinctive and compelling and give us a better understanding of the lives and personal stories of the Americas’ first Muslims.