How you defend yourself will change you.

Anti-Muslim bigotry is a major problem confronting all Muslims in one way or another. We are undermined, challenged, and targeted in a daunting variety of ways, and the way we face this challenge will be woven into the fabric of our souls, whether we like it or not. Unfortunately, many intellectuals are responding to anti-Muslim bigotry, commonly referred to as Islamophobia, with arguments whose ultimate and often overlooked presuppositions are antithetical not only to Islam but to religion as such. A growing, even dominant, trend in recent scholarly and activist literature frames Islamophobia as a form of racism.1 In this particular approach, anti-Muslim bigotry is not a phenomenon with a racial component or a racist dimension; rather, Islamophobia simply is a form of racism, or originates in racism, or should be studied through the framework of racism.

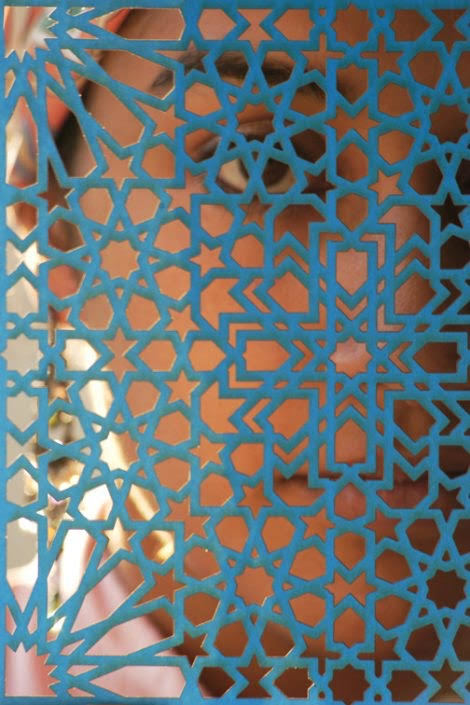

Photo: Peter Sanders

The formulation “Islamophobia is anti-Muslim racism” is, at its best, intended to leverage existing legal protections for racial minorities and to benefit from the social stigma against racism, with the worthy goal of protecting vulnerable people from racism disguised as a concern for national security or culture or as a “critique of ideas.” But the reduction of Islamophobia to racism muddles our understanding of other real motives behind anti-Muslim bigotry and depends on misused or simply confused ideas such as “racialization” that are difficult for many people to grasp. Worse than that, the conceptual apparatus underpinning “Islamophobia is racism” turns Islam into a mere cultural marker of non-white people, a cipher that is spiritually, intellectually, and morally inert. The exclusively “racist” framework—in a world where human beings are motivated by many kinds of irrationality, egotism, and fanaticism—makes it seem that Islam could only be interesting or challenging insofar as it is the patrimony of non-white people. Religion becomes just one more social factor in a world where human affairs are reduced entirely to race, class, gender, and sexuality.

To be clear, I am not rejecting formulations such as “Islamophobia and racism have significant overlap” or “Racism is a major component of Islamophobia,” which were once the norm in describing the intersection between Islam and race. My objection is to those more recent theorizing attempts that say all Islamophobia is understandable as racism, or in what amounts to the same, the implication that the only form of anti-Muslim bigotry that matters is racist in character.2

***

Most people use the word “racism” to refer to an act or attitude of prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism against a member of another (perceived) race on the basis of his or her appearance or racial origin. According to this commonplace understanding of the word, racism is a fault in the character of the racist, and by implication, his or her ignorance and prejudice can potentially be rectified through the cultivation of knowledge, empathy, and good will. But today racism means much more—or even something else entirely—among many sociologists, anthropologists, legal scholars, philosophers, and activists. In this expanded sense, racism is a structure or a system. It is not only a matter of intention but is also—or even primarily—a matter of effects and results. Wealth disparities can be effectively racist without being intentionally so at the personal level, because the racism is a trait of the system or structure.

Many academics and activists came to believe that ... [r]acism was not a problem of bad people operating irrationally within a fair and rational system; rather, the system was itself racist and depended on racism.

One motive for this extension of racism beyond individual intention was the perceived failure of people to understand the subtle ways that profound inequalities have persisted even after explicit racism became unacceptable in much of public life. Some scholars and activists have argued that the civil rights era’s project of racial universalism and legal equality has failed, and that the very laws and other measures ostensibly meant to counter racism have been used as a smoke-screen to effectively perpetuate racial discrimination in covert ways. Society may have banished the most explicit and extreme racism from public view, but racist discrimination continued to function within and through the “color-blind” and “post-racial” structures. Many academics and activists came to believe that racism was not a problem of changing individual minds, and that it was incorrect to treat racism as either irrational or aberrational. Racism was not a problem of bad people operating irrationally within a fair and rational system; rather, the system was itself racist and depended on racism.

Alongside this emphasis on structural racism was the belief that racism cannot be treated separately from other forms of oppression that make up the system: racist, misogynist, and classist discrimination constitute a matrix of oppression. There is one system. In the old conception, all such forms of prejudice and discrimination were bad, but they were different from each other and could be analyzed accordingly. The new approach toward these categories (beginning with race and gender) sees them not as separate but as intersecting hierarchies of oppression. For example, in the case of black women, it is impossible to isolate racism and sexism because in practice the two reinforce one another, and therefore the experience of oppression by black women is not comprehensible merely as racism here and sexism there but is its own reality. Intersectionality, as this approach came to be known, is a natural extension of the move toward structures and systems: a large social, economic, and political structure can be racist, misogynist, and classist all at once in mutually reinforcing ways that cannot be laid easily at the feet of any particular individual.

How do Muslims, then, as a religious group, fit into the idea of structural racism and the intersectionality of oppression? While Islam is not a race, it is argued that Muslims can nevertheless be racialized. Racialization is a contested concept that arose in scholarly circles in the wake of the gradual discrediting (not disappearance) of doctrines of biological superiority and difference, which led—in some circles—to a shift from race to culture as the marker of group superiority. White people could no longer speak openly about being biologically superior but could claim to have a superior culture that makes them more advanced, developed, and civilized, and this cultural superiority is then used to justify policies of domination and exclusion. This phenomenon came to be labelled by some as cultural racism, using the argument that identities such as “Arab” and “Muslim” can be subjected to exclusion and discrimination in ways that mirror explicit racism, and hence these groups can be racialized even in the absence of any articulated notion of race. In this view, “Muslim” can be treated as if it were a racial category, without being one explicitly. The difficulty with applying this concept to Muslims is that racialization originated in the earlier concept of racial formation, referring to the ways in which racial groupings are constructed and change over time. These are not just any groupings, but racial ones, which have at their core a notion of physical differentiation. A racial identity is not reducible to such bodily differences, but without them, the notion of “racial group” loses its meaning.3

But before exploring just how “Muslim” could be a racial identity, a serious implication of this notion of racialization must not go unnoticed. Recall that, while the system is racist, it is also misogynist, homophobic, and classist. When the new approach to Islamophobia asks us to understand anti-Muslim bigotry through the lens of racism or to see Muslims as a racialized group, it leaves misogyny and homophobia intact in their own independent categories. Muslims are racialized, but gays are not “religionized.” Are groups “genderized” or “queerized”? We can say, “Islamophobia is racism” but not “Misogyny is racism” or “Homophobia is misogyny” or “Racism is homophobia.” Racism and sexism can intersect because race and gender cannot be reduced to each other, and that irreducibility means racial oppression and gender oppression are not to be treated as forms of each other. The way Islam is brought into the framework of intersectionality does not add another parameter of discrimination (that of religious bigotry) to the existing matrix of oppression but instead inserts religion into the already existing hierarchy by using the concept of racialization.4 In this view, only races, genders, classes, and sexual orientations constitute real groups. Religious bigotry sits on the lap of racism instead of having its own seat at the table of intersecting hierarchies.

Why? If Islamophobia is a form of racism, what is racism a form of?

***

The intellectual underpinnings of both the expansion of racism to include structures and effects and the treatment of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia as the only real intertwining threads in a fabric of oppression are essentially postmodern in character. Critical race theory (CRT), for example, grew out of critical legal studies (CLS), which was based upon the work of thinkers in the movement of critical theory (and other forms of philosophy with Marxist roots) who had abandoned the “scientific” pretensions of Marxism and moved on to a new mode of thinking that focused not only on class but on a general critique of “culture” and “identity.”5 Postmodern thinkers, in general, are suspicious of truth and objectivity and see claims to objective knowledge as a manifestation of a will to power or some other drive. Behind claims of truth and morality, they argue, there is always a desire to dominate, an impulse to use reason and universality as a means of control. Human beings are products of their cultural conditions. They do not express their culture; their culture expresses them. So, when someone has beliefs about the truth or the good, these convictions are by definition not the result of a self-aware human soul capable of stepping outside itself and rising above circumstances but are merely part of an identity that has been formed by the structures in which one has been raised. This is a definite vision of the world. Indeed, critical theory, Foucauldian genealogy, Derridean deconstruction, Lacanian psychoanalysis, and other varieties of postmodernism do not merely offer a neutral method of critique that Muslims or other religious believers can use to solve problems. To believe that reality is what the Qur’an says, while also exploring fundamental questions of human nature using the methods of a Foucault or a Lacan or a Derrida, is to live, at best, in a state of extreme tension. One believes in God but devotes one’s rational and reflective mind to a way of thinking that hinges on the belief that He does not exist. One believes that one must transform one’s soul and choose the good while also arguing that one’s very sense of the good is determined by social structures of domination and the relationships between “bodies.” Human beings live with all kinds of contradictions, but these are among the most consequential.

While postmodern thinkers claim to reject truth claims and moral objectivity in favor of a mode of action, they still have definite answers to ultimate questions and unshakeable commitments to their own beliefs. Their failure to admit the performative self-contradiction in arguing against rationality or in a commitment to moral relativism does not obligate us to participate in ideas that are incoherent at best. To argue against truth, or to be committed to moral relativism, is to presuppose both the objective truth and the morality of one’s own position.

Podcast: Are Believers a Political Tribe? with Asma Uddin and Caner K. Dagli

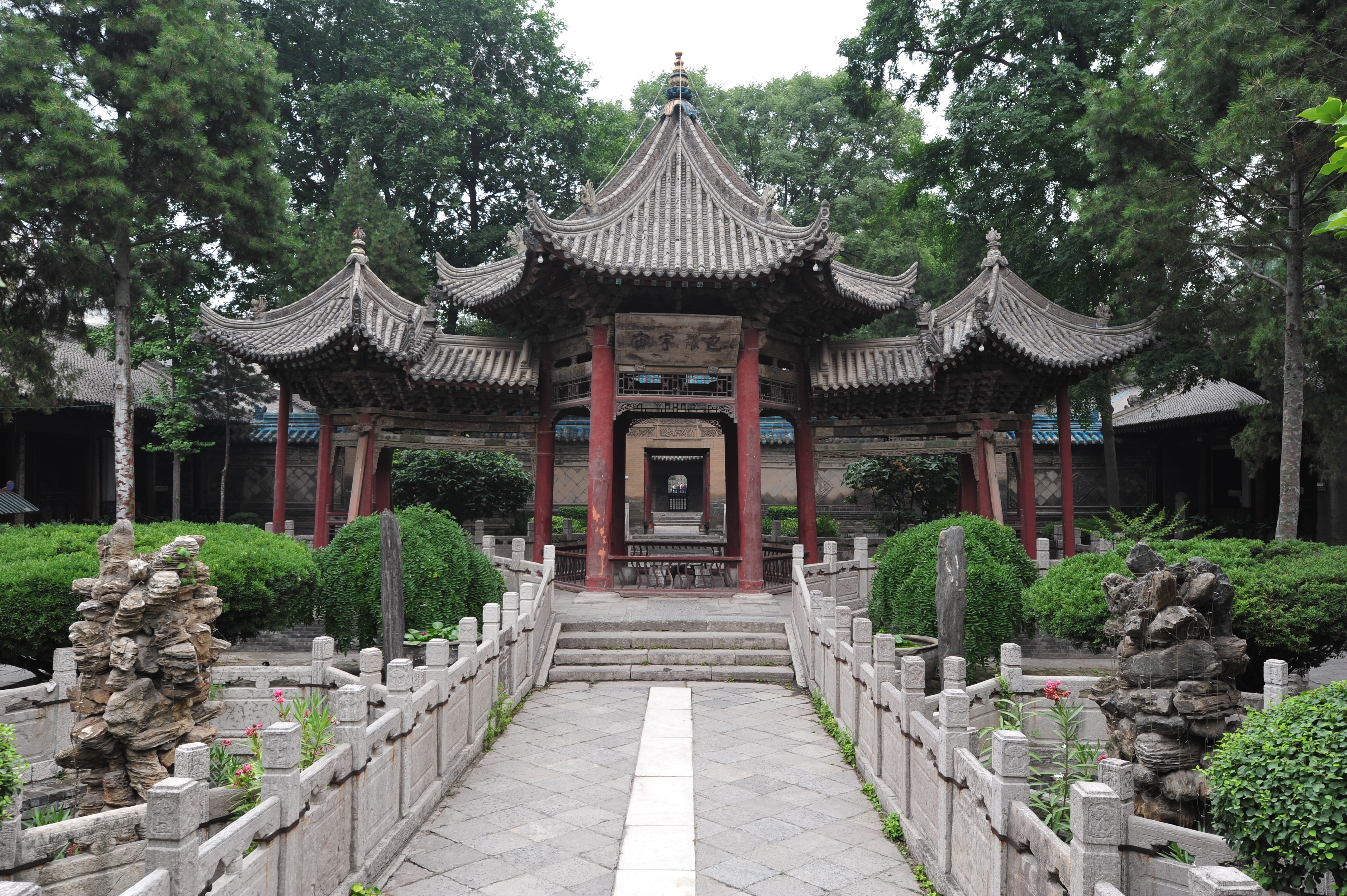

Great Mosque of Xian, China; photo: Wikimedia Commons, chensiyuan

Postmodernists, in fact, have a clear idea of what reality is and what it is not, and it is on the basis of those assumptions that they interpret the world and make moral demands. It is not at all trivial that not a single one of the philosophers at the deep root of “cultural racism” and “intersectionality” accept God or the existence of the soul. All of them believe that human beings are biological machines destined for oblivion in an unconscious universe and that those who avoid such matters of human nature and destiny defer unfailingly to the authority of those who do.

Such thinkers do not want to hear about a soul that can transcend its egotism or about misfortune being a test from God or about the impossibility of perfect justice in this world or about responding to evil with good.6 Postmodernists have given themselves a way of speaking about such abiding teachings as nothing more than delusions or tricks used to maintain a system of domination where the rich take from the poor, men take from women, and whites take from people of color. They believe they are liberating people (or “bodies”), but they also have different answers to ultimate questions. They believe one can only be realistic and sophisticated about racism (and other social ills) if one stops taking religious teachings seriously.

But religious teachings are serious. Among the relevant religious teachings, of course, is a firm conviction that human beings can cultivate true rationality and morality. A human being has a soul that is capable of both good and evil, and one can overcome one’s own egotism to reach the truth and to choose the good—even if most fail to do so. In the eyes of the postmodernists, such notions are quaint at best. For them, the ego is not the lower self but the only one, and what traditional religion would call reason or spirit or self-awareness are stories the powerful tell the powerless. The postmodern conception of the human self, then, amounts to a flipping upside down of the relationship between reason and passion. The rational/irrational dichotomy is rendered meaningless.

The way Islam is brought into the framework of intersectionality does not add [religious bigotry] to the existing matrix of oppression…only races, genders, classes, and sexual orientations constitute real groups. Religious bigotry sits on the lap of racism instead of having its own seat at the table of intersecting hierarchies.

In the postmodern view, racism is primarily about systems and structures because those systems and structures are the real cause of what we naively consider to be personal bigotry; fashioned by our material conditions, our impulses generate such quaint notions as truth and rightness to get what they want. Religion cannot be a real cause of human behavior because of its concern with truth and rightness, ideas that are merely derivative of impulses to dominate other racial groups, or to subjugate women, or to acquire wealth, and other such “real” factors.

***

The postmodern way of approaching problems creates patterns of thought that slowly poison the soul. When one treats a form of irrational egotism, such as racism or religious bigotry, purely as a product of identity that can be checked only through power, one ceases to take seriously the possibility of human growth and understanding. If one’s reflex in dealing with human problems is to treat them all as functions of a socio-political structure and to see people only in terms of their inescapable “identity,” then what is left of the notion of the spiritual life in Islam—the purification of the soul, the cultivation of love for God and the Prophet ﷺ, the deepening of consciousness? Through responding to prejudice and bigotry as quasi-mechanical functions of a matrix of oppression, one reinforces within oneself an attitude that says that human beings are mere products of their cultures and that the only way to change anything is through power. Politics becomes everything, and only the cynic can be sophisticated.

Podcast: Why Are Muslims Seen as a Race? with Khalil Abdur Rashid and Caner K. Dagli

Jama Masjid, Delhi, India; photo: Dan Davies / New World Encyclopedia

Such insidious mental habits are bad enough, but far worse is when the postmodern method of critique is turned explicitly on religion itself, as when the message of Islam gets caught up in the postmodern reaction against liberal “color blindness.” The Qur’an and the life of the Prophet ﷺ do, in fact, ask human beings to look beyond skin color and tribal origins and to judge people by their hearts and their conduct. Muslims are completely justified in saying their religion deplores racism and are right to point to the Prophet ﷺ as explicitly ruling out superiority on the basis of any conception of race. The history of racism and tribalism among Muslims cannot alter Islam’s teachings on race any more than the presence of alcoholism can alter its teachings on drinking. Racism is a sickness from which Muslims are far from immune, though their religion does give them a medicine for it. The Qur’anic message is not, in any case, a color-blind one but a celebration of the richness and diversity of human beings. Sadly, Muslims who celebrate the anti-racism and anti-tribalism of Islam are sometimes accused of obscuring the problem of white supremacy, but such teachings are not the concoction of a system trying to perpetuate itself by adopting a universalist discourse as a fig leaf. The Prophet ﷺ really did teach it. Islam really is universalist in its teachings on race.

However, Muslims are not confined to a naive “love overcomes hate” or “hatred is born of ignorance” message when it comes to racism. Indeed, hatred and ignorance are forms of egotism, but so are tribalism, greed, and jealousy. We should not abandon a profound doctrine of human nature because of the pretense by certain latter-day philosophers that they alone have discovered how people can organize to create unjust systems they claim are just. “When it is said to them, ‘Do not be corrupt in the land,’ they say, ‘We are the righteous’” (Qur’an 2:11). Indeed, one of the most terrifying teachings of the Qur’an is its description of the category of people who believe they are doing good but, in reality, are not, and this extends to claims of color blindness and racial equality as well. The desire for supremacy is a deep part of the human ego. The Sufis say the last vice to leave the soul of the sincerest people is the desire to be in charge. We do not need the postmodernists to tell us that, but we should not forget it either.

Muslims can and should maintain a sophisticated theory of racism, addressing the subtle and hidden ways bigotry can manifest and also the ways in which inequalities can persist across generations and between domains of life as a result of malice, delusion, incompetence, and ignorance. But such a theory should not obligate them to place their faith in God, the soul, or the hereafter at an ironic distance. They would do well to remember that the discourse about racialization, intersectionality, et cetera is not merely some purely theoretical or value-neutral method of structural analysis; it traces itself back to a bleak, meaningless, and false philosophical picture of the world, whether that worldview is acknowledged explicitly or not. These ideas have permeated academic fields, such as law, sociology, anthropology, history, and comparative literature, and from there they have influenced activists, journalists, human rights organizations, and think tanks. Today, they have crept their way into the definition of anti-Muslim bigotry and, by implication, into the definition of Islam.

***

The impact of the aforementioned philosophical ideas can be seen in the drastic difference between the influential Runnymede Trust report of 1997 and its twentieth anniversary report of 2017. The Runnymede reports are good examples to highlight because the two reports come from the same organization and are illustrative of the changes in approach to anti-Muslim bigotry. The 1997 report framed its findings about anti-Muslim bigotry around ideas such as “hostility and prejudice,” setting up nuanced parameters of discussion based upon “open” and “closed” views of Islam. Alongside the attention it gave to stereotyping and ignorance, the report also noted that “Islamophobia in Britain is often mixed with racism…. A closed view of Islam has the effect of justifying such racism.”7 The role of racism was important but certainly was not the dominant theme in the 1997 report. The 2017 report—like much contemporary discourse about Islamophobia—overturns Runnymede’s previous approach, abrogating the 1997 report’s definition of Islamophobia (which does not mention racism) and redefining it as follows: “Definition: Islamophobia is anti-Muslim racism.”8

The mosque of Dar al-Islam, New Mexico

The 2017 report justifies this redefinition in part by saying, “Among sociologists it is common to talk about different forms of racism, processes of ‘racialization’, and even ‘racism without races’. The notion that race is a social construct is more familiar today and indeed widely affirmed even outside the university and across the political spectrum.”9 Against other possible definitions, it argues, “Referring only to anti-Muslim hate (or even anti-Muslim prejudice and discrimination) doesn’t fully capture the widespread (or structural) ways racial inequalities persist.”10

But why should “racial inequalities” and their persistence be made paramount over other types of discrimination? There is a kind of question-begging here: we are told it is incorrect to call anti-Muslim racism “anti-Muslim prejudice” because it does not fully capture anti-Muslim racism. How did we establish in the first place that we are dealing with only anti-Muslim racism, or that the only such racism that matters is structural? The new definition overturns the old one by simply presupposing itself to be right.

Moreover, while it may be the case that some sociologists talk about “structural racism,” “racialization,” or “racism without races,” it is also the case that, for better or worse, the general public does not really understand these specialized notions and will carry on using the everyday sense of what it means to be racist. Should people change their sense of “truth” and “meaning,” for example, because academic philosophers say that truth is “that which is useful to believe” or that meaning consists of the “truth conditions” of a sentence? Should one try to formulate policy and connect with the broad public on the basis of such recondite definitions, or should one work on the basis of how those words are actually used by competent speakers of the language? People already know what prejudice, bigotry, stereotypes, and bias are, and they will understand a definition that speaks in those terms.

The Grand Mosque of Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso; photo: Flickr, qiv

Racialization is already highly contested even in those areas where it has some relevance, but when applied to religion, it amounts to an ad hoc method of shoehorning religious bigotry into one of the categories one is willing to accept—either race, gender, class, or sexual orientation. It is very difficult indeed to find any examples of the so-called racialization of Muslims or Islam that cannot be understood more clearly and more correctly as “stereotyping” or “prejudice.”11 All instances of stereotyping, pigeonholing, prejudice, and clichés about Muslims are automatically reclassified as “racism” or “racialization.”12 But this is a mistake, because racialization—or racial formation—is about race. But Muslims are not a race, and no one thinks they are a race, and the term racialization only makes sense if someone believes, at some level, that the group involved is differentiated racially. Are all forms of sectarianism instances of racialization?

And the notion of “race as a social construct” only makes sense if we can answer the question: a construct of what? To simply call something a “construct” is like calling it an “illusion”: it has to be a construct or illusion of something. A desert mirage is an illusion of water, not trees. Roughly speaking, race is a construct of irreversible, hereditary, physical differences resulting in meaningful variations in intelligence and morality between different groups of human beings.13 When one calls race a “construct,” one does not mean people cannot actually divide human beings into groups; after all, one could divide human beings by thumbnail shape and give those groups proper names. What one means is that such divisions do not cut the world “at the joints” and that the taxonomy according to “race” does not capture any important or consequential differences between human groups. But for racists, races are not a construct: they are real and meaningful. If no superficial differences are available—skin color, for example—racists will find other hidden differences (brain size, skull shape, DNA percentages, or simply a vague sense of heredity). Race always has a supposed aspect of biological or bodily differentiation at its core. These bodily differences are often imputed after the fact in an ad hoc fashion to justify existing hierarchies, as in the abuse of IQ tests by some extreme opponents of affirmative action programs. But without the belief in such imagined differences, there are neither races nor racialized groups.14

Not a single one of the philosophers at the deep root of “cultural racism” and “intersectionality” accept God or the existence of the soul. All of them believe that human beings are biological machines destined for oblivion in an unconscious universe.

Indeed, race is a social construct, but so what? Religions are not simply groups of bodies. The application of “race as a social construct” to religious intolerance or bigotry is a category error. It is an idea, like racialization or racial formation, that can only be useful in its own relevant domain—that of people who still cling in some way to the notion that racial differences exist and that those bodily/biological variations matter. Such ideas can help us understand Islamophobia only insofar as the bigots in question are racists and their hatred of Muslims is derivative of their hatred for another race of people. Otherwise, we first have to presuppose that all anti-Muslim hostility is racism before the concept of “race as a social construct” becomes relevant to the understanding of Islamophobia.15

***

Calling Muslims’ antagonists “racist” can be a potent argument in the court of public opinion, but does that mean the accusation of racism will always be true or even make sense? Christians have been preaching against Muslims for fourteen centuries. Were they all racists? Philosophers since the Renaissance have mocked and derided traditional Christianity in terms similar to those they used for traditional Islam; does racism really explain all of that? Surely some of it, but all of it?

Racially motivated people who attack Islam or Muslims often hide behind statements such as “I’m just critiquing ideas” or “Some values are better than others”; they may even deny the very category of Islamophobia. But if one wants to hold to a meaningful conception of Islam that actually is constituted by a set of ideas and values, then the possibility of a racist masking his racism behind such tactics is a risk one must live with if one wishes to maintain spiritual integrity.16 I recognize that Muslims feel vulnerable, are on the defense, and are exhausted with having to explain themselves over and over again in the face of bad-faith demands to “condemn” this or that. Racism—stupid, ignorant, cruel bigotry—is often a reason for the barrage. But it still does not mean one should automatically classify all anti-Muslim hostility as racist, and the ad hoc invocation of racialization to enable such blanket classification is not a good solution.17

The problem with this approach—defining Islamophobia as racism, and marshalling ideas like racialization and structural racism—is that it implies that it simply does not matter what Muslims believe or do or what kind of human beings they are. It only matters that Muslims are not white and that Islam is the religion of non-white people. It means no reasons other than race can explain why a non-Muslim would be hostile toward Muslims or why a powerful institution might perpetuate antagonism toward Muslims. Islam is only interesting or important insofar as it is a racial signifier. When we teach people to respond to anti-Muslim bigotry by calling all such bigotry “racism,” we are training them to believe Islam is no more meaningful than an accent that allows white people to identify non-whites.18

Should one believe the headscarf is treated with hostility only as a “visible marker” of some racial animus? Are there no principles behind Muslim social comportment that others might find repulsive on principle? Is there nothing in the spiritual and intellectual message of Islam that large numbers of people might find threatening as ideas? When the Qur’an describes the rampant hostility of various groups to the early Muslim community, is that all simply racism? What would be the meaning of “To you your religion (dīn), and to me, my religion” (109:6) if really it were about race or cultural racism? Did Abū Lahab fight his nephew the Prophet ﷺ because the believers were racialized? When the Qur’an says over and over that believing communities throughout history were attacked because they said, “Our Lord is God,” is it talking about cultural racism?

We know from common experience that human beings are capable of irrational attachments and hostilities for many reasons, and yet the only reason anyone could have a prejudice against Islam and Muslims is racism? How dull and empty Islam must be!

Muslims who adopt the discourse of critical race theory and related approaches (consciously or not) must remember that the originators of these ideas were not concerned with religion at all. They were concerned with race, gender, sexuality, and class—full stop. If theorists and activists only care about Islam as the patrimony of non-whites and as an aspect of non-white subjectivity or identity, then that is their business. One should not have to feed one’s religion through the postmodern shredder in order to help oppressed people or to free oneself from oppression. Muslims must deal with the problems of the world on their own intellectual terms. Sophistication about worldly matters need not come at the price of one’s ultimate commitments. Muslims are facing unrelenting enmity from all sides, and responding to anti-Muslim bigotry (or at least being forced to think about it) is a fact of daily life. How we choose to face it cannot possibly fail to transform us as human beings—for better or for worse.

Lest this sustained attention to concepts and their philosophical origins be dismissed as too abstract, let us invert the racialization of Muslims, structural racism, and racism without racists. Muslims might point to the “structural anti-theism” of academia and intellectual life, which often functions as a machinery of “anti-theism without anti-theists.” We are told that the color-blind and post-racial society masks and perpetuates racism, but what if Muslims said that the claims to be a faith-blind society—in which we do not judge people by where they worship but by how they treat others—only serve to perpetuate the rampant scientism, materialism, and nihilism that are the real dominant religion; science may not be a religion per se, but it has been “religionized.” We are sometimes asked to be conscious of micro-aggressions and subtle exclusions that take a real psychological toll on minorities, but Muslims can point to an intellectual and artistic culture that seems designed to make it difficult or impossible to remember God and to cultivate an inner life. It is a cacophony of metaphysical micro-aggressions.

Cambridge Central Mosque, United Kingdom; photo: Wikimedia Commons, cmglee

I do not at all favor using such jargon to speak about the tribulations of the world. I only mean to highlight the fact that theories and definitions are not neutral and that they necessarily draw from and are oriented toward ultimate commitments that are not always universally held. I doubt very much that any adherents of Foucault, for example, would accede to their fields being defined as “structurally anti-theist” or to Darwinism as their dominant religion, because the very concepts are infused with presuppositions they would not be prepared to accept. It would not matter if they were told that structural anti-theism means this or that among professional theologians or that religionization is a widely accepted concept in seminaries. They would understand that to adopt a discourse based around the religionization of science and the structural anti-theism of academia would commit them to certain presuppositions, even if those presuppositions were not immediately apparent or explicitly discussed and even if such ideas were being used to help the people they were interested in helping.19

Let us also be aware of the danger of crying wolf. The truth is that racism—ignorant, egotistical, cruel hatred based upon perceived irreversible hereditary biological differences—is alive and well and is one of the most powerful forces creating evil in the world. I dare say that, in many instances, racism is such a major component of anti-Muslim hatred that simply calling Islamophobia “racism” can work as a first approximation. But when one labels as “racist” things that are not obviously racist and that require a hopeless redefinition of “racism” to include almost any group hatred, then eventually the accusation of “racist” will lose its power, because it will not ring true and will carry the whiff of expediency. Not only will it not help us to understand the non-racist motivations behind Islamophobia that are absolutely crucial to understand, but it also will deprive us of the ability to properly identify and deal with the actually racist component of Islamophobia (and one ought to mention, the racism of Muslims themselves). For related reasons, I tend to think that calling all anti-Muslim bigotry “racist” will come to be perceived by racial minorities as parasitic and opportunistic—and here I am thinking particularly of the American case. African Americans (Muslim and non-Muslim), for example, may grow to resent the fact that many Muslims took the social capital African Americans built over decades of struggle and sacrifice and expended it in their own cause without caring about the difference between actual racial supremacism and other forms of bigotry, intolerance, and prejudice.

Besides, has the attempt to reframe Islamophobia as racism actually led to good outcomes or raised awareness that could not have been reached in a better way—one that does not reduce religion to a marker of race? Let us not forget that bigotry and prejudice against Muslims were deplored and fought long before these new definitions of Islamophobia came along. Different faith leaders have made genuine attempts to reduce religious bigotry and have sometimes succeeded. For decades, human rights law and international organizations have taken the category of religious discrimination seriously on its own terms. Muslims in America, for example, should not fall into the hands of those enemies of Islam who wish to define Islam precisely as something other than a religion; rather, they should act to preserve the broad First Amendment protections (i.e., the free exercise clause) that have been built up over time to protect expressions of faith.20 One can build upon that history, rather than discard it, to create a nuanced and effective concept of anti-Muslim discrimination that includes racism but is not encircled by it.

The Qur’an speaks of the pagan society and religion of the pre-Islamic Arabs as jāhiliyyah—a word encompassing both ignorance and bad character. A jāhil is a person who fails to understand the difference between right and wrong in both of these senses. But the jāhiliyyah was not entirely bad: Islam retained and celebrated what was good about that society, and human beings who were individually ignorant and bad could gain knowledge and rectify their character. In the face of racism, degradation of women, oppression of the poor, torture, exile, and death, the Prophet ﷺ never resorted to arguments about “structural jāhiliyyah” or “jāhiliyyah without jāhils.” He was politically savvy, but he was no cynic. Muslims must never abandon their belief that human beings are capable of knowledge and goodness, that God’s will is paramount, and that He can guide anyone. They should reject a view of human nature in which the notions of prejudice and ignorance are rendered defunct because judgment and knowledge are really just forms of the will to power. When one thinks that way, one will inevitably begin to believe that one can only overpower, not teach, and that one can only defeat or be defeated, not win over or be won over. In the long run, that will bring out the worst in people, not the best.

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy