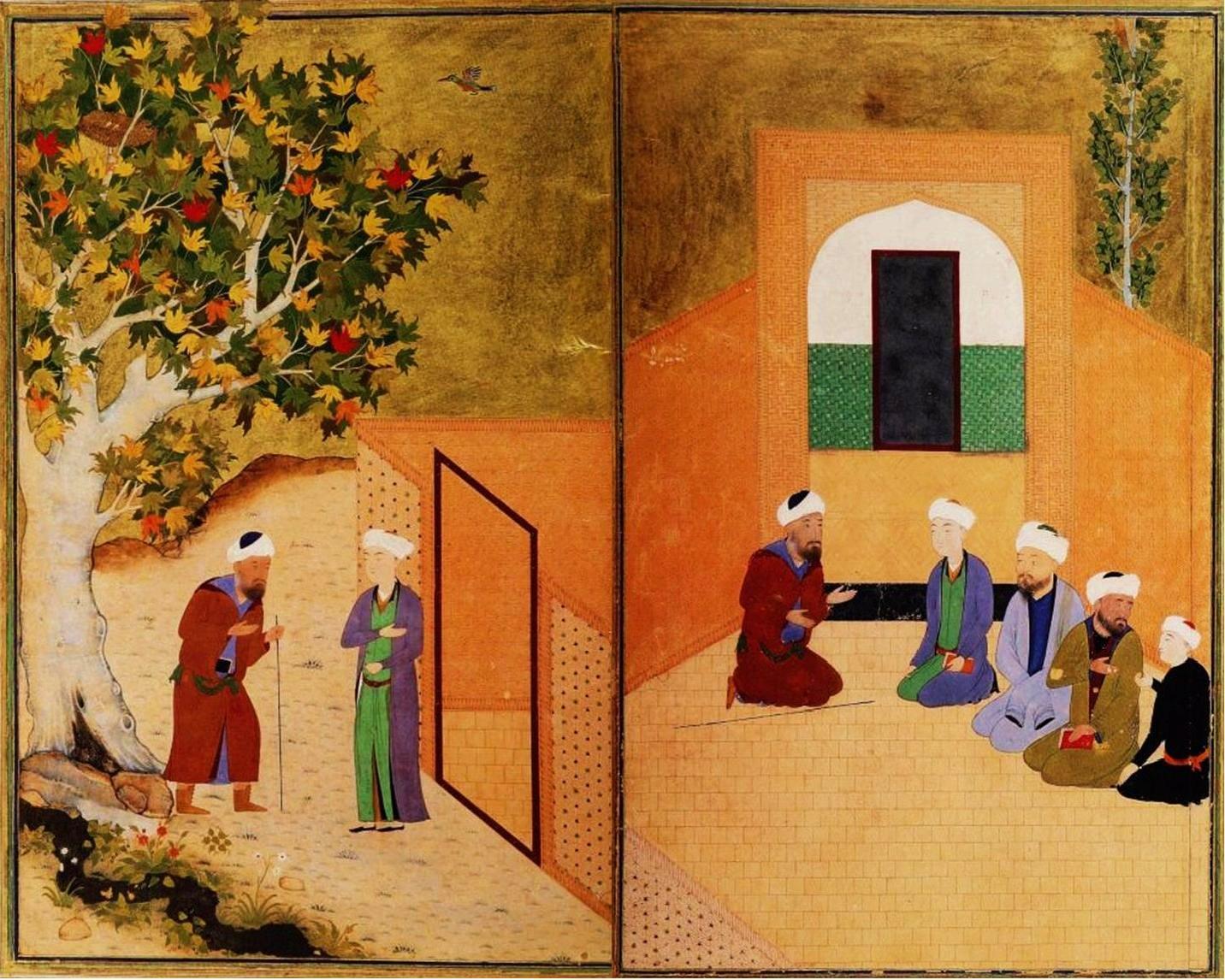

Sa¢dī and the youth of Kashgar, Bukhara, 1547

One of the most significant facts about us may finally be that we all begin with the natural equipment to live a thousand kinds of life but end in the end having lived only one.1 —Clifford Geertz

Once, a king decided that a certain prisoner should be executed. Having lost hope in being pardoned, the prisoner began to insult the king. The king asked those around him what the prisoner said. One of his viziers, whose kindness made for “pleasant company,” responded with a lie, reporting to the king that the prisoner had actually pleaded for mercy. “O commander of the world,” the vizier declared, “the prisoner says, ‘And those who restrain their anger and pardon people,’” quoting part of a Qurʾanic verse that praises those who forgive others and act excellently.2 The king, moved by these words, decided to pardon the prisoner.

Through this story, which begins his masterpiece The Rose Garden (Gulistān), Sa¢dī—or more completely, Musharrif al-Dīn Muśliĥ Sa¢dī (d. ca. 690/1291), often considered the greatest moralist of Persian literature—explores the ethics of lying. The story continues that another vizier, however, intervened: “To speak anything but the truth in the presence of the king does not befit my kind. He insulted the king and hurled obscenities at him.” Hearing this, the king grimaced and replied, “I prefer that lie to this truth that you’ve uttered because that was aimed at best interests, while this was rooted in vice.” Sa¢dī then offers a choice saying of the wise: “A lie that furthers what is best is better than a truth that arouses sedition.”

In fact, one of Sa¢dī’s most famous set of verses concerns humanity’s essential unity. Early in The Rose Garden, he tells of a certain tyrant whom he saw while in spiritual retreat by the burial place of John the Baptist, in the Umayyad Mosque, in Damascus. Fearing a dangerous foe, the tyrant sought the world-renouncing Sa¢dī’s prayers, to which he responded, “Have mercy upon the weak subject so that you avoid the pains of your strong enemy.”16 This then leads the author to contemplate empathy within the context of a universal sense of humanity:

The children of Adam are limbs of one another,

from one essential origin in their creation.

When fate causes one limb to suffer,

the other limbs can find no comfort.

You who feel no grief at others’ affliction

are unfit to be called a human being.16

It is not enough to be attuned to the humanity we share. Rather, we must also be cognizant of the differences in privilege and comfort that separate us. While being of one “essential origin” matters, it matters as well that a person does not mistake his or her individual ease with a universal state of well-being. It is not, in other words, that all humans are one; were that the case, the well-being of one person might suffice for the whole. Instead, they make up composite parts of one humanity, with a shared purpose to serve God and promote the good. For that reason, each part must be aware of the trials of the others, reacting with both empathy and support.

Such empathy does not merely apply to appreciating hardship but also to appreciating another’s degree of wisdom and life circumstances. Thus, returning to the story of the wrestler, when viewed through the lens of love and empathy, the father can understand why his son would risk adventure and perhaps even succeed, even when contentment is the wiser option. Sa¢dī makes such allowances in a discussion of the cypress. In Persian, various species of evergreen conifers—usually varieties of the Mediterranean cypress (Cupressus sempervirens)—are called sarw, with specific descriptors to differentiate them. The sarw-i nāz (the “elegant” cypress), for example, has soft needles. One very admired species of evergreen—with straighter needles—is the sarw-i āzād (the “noble” or “free” cypress). Sa¢dī tells of a group wondering about the origins of that tree’s name:

A wise man was asked, “Of all the distinguished species of tree that God, Almighty and Glorified, has created, none but the cypress is called ‘free.’ Yet it bears no fruit. What is the wisdom behind this?” He responded, “Each of them has a specific yield during a certain season. For that reason, at times those trees are in season, while at other times they wither. The cypress does not go through such cycles and is always well. Such is the attribute of the free.”

Don’t give your heart over to that which passes, for the Tigris

will keep on flowing through Baghdad, even when the Caliph’s gone.

If you are able, then be like the date palm: generous.

And if you are not, then be like the cypress: free.17

The date palm bears fruit in every season, as alluded to in the Qurʾan.18 In Sa¢dī’s poem, it represents the person who has wealth and gives to others generously. Such generosity is the preferable option. Yet there are those who either do not have wealth or cannot be generous. For them, a less preferable and yet still noble option exists: be so unattached and indifferent to wealth that you are free from want. While barren, like the cypress, such a “free” person does not experience the vacillations of joy and despair that come from placing one’s hopes in worldly pursuits. The free person’s well-being does not depend on his or her physical or financial well-being because he or she has no interest in such things. Note, however, that this is not an ideal. Recognizing the relationship between ascetics and their patrons that existed in his day, as well as the relationship between the creatures and God as their provider, Sa¢dī acknowledges the superiority of those who have wealth but remain sufficiently unattached and indifferent to the wealth that they give freely. This is a more godly sort of relationship to the world, even if another sort of virtuous relationship (indifference and poverty) exists. Note also that a range of virtuousness appears between these two extremes: some have moderate amounts of wealth and give of what they have while remaining indifferent to what they do not have.

It is such adaptability that renders Sa¢dī’s ethics truer to the situations in which we live where universal principles often cannot be applied. His is not a philosophical approach but a literary one—a literary ethics common to much of the wisdom literature found throughout the world. Literature, and especially storytelling, can be used to teach, to preach, to express mystical visions, as well as to convey a sort of real ethics—an ethics of marketplaces, homes, and other sites of lived experience, as opposed to an ethics of scholarly books.19 Such a real ethics takes into account the variety of perspectives and abilities that interact in the world. Yet Sa¢dī also embraces a worldview in which humans trace themselves to a common origin and should answer a universal call to be decent, wise, indifferent to the worldly, and mindful of God. He presents, in other words, the human being in a manner that MacIntyre argues gives morality a sense of factuality, as “having an essential nature and an essential purpose or function.”20 The underlying impetus of human good, for Sa¢dī, is love—more specifically, the love of God:

Whoever loves something will give both heart and soul over to it.

Whoever has you for a prayer-niche (miĥrāb) will not lift his head from seclusion. . . .

Whoever plants a tree within the garden of spiritual meanings,

has buried his roots within the heart and sewn his seed within the soul.21

The highest achievement of humanity is to give oneself over to God, going beyond the role of obedient servant to become the humbled and overwhelmed lover. All of us, Sa¢dī says, lose ourselves to what we love. If we can lose ourselves to God, then difficult acts of devotion—such as seclusion from others (khalwat)—can bring us such pleasure, that nothing could take the place of solitary intimacy with the divine beloved. Those who concern themselves with what lies beyond the visible domain around them become a people of “heart” and “soul,” that is, people concerned with the interior dimensions of human reality—those dimensions in communication with God. All differences aside, this is—for Sa¢dī and so many others—a universal end for which all humans should strive. In the words of the Qurʾan, “Let those who vie with one another endeavor for that” (83:26).

Renovatio is free to read online, but you can support our work by buying the print edition or making a donation.

Browse and Buy